A Tale of Three Elders - Democracy, Oppression and Liberty

In 2016, Mr Pascoe was joint winner of the $30,000, NSW Premier’s Literary Awards 2016-Indigenous Writers Prize, for his book Dark Emu, which the judges highly praised with comments such as,

‘Pascoe demonstrates with convincing evidence, often from explorers journals that Aboriginal peoples lived settled and sophisticated lives here for millennia before Cook. Aboriginal democracy created ‘the Great Australian Peace’ on a continent that was extensively farmed, skilfully managed and deeply loved.’

- Dark Emu front-pages 2018 Reprint - [our emphasis].

And initially we too believed, like Lisa Hill, blogger and educator, who is quoted in Dark Emu with her glowing reference, that Mr Pascoe had ‘discovered’ the real story of pre-colonial Australia.

‘Pascoe has inverted almost everything I thought I knew about pre-colonial Australia. Importantly he’s not relying on oral history, which runs the risk of being too easily debunked; his sources are the journals of notable explorers and surveyors, of pastoralists and protectors. He quotes them verbatim, describing all the signs of a complex civilization but viewed through the blinkered lens of appropriation and White superiority…’,

- Lisa Hill, blogger and educator Dark Emu fore-pages, 2018 Reprint - [our emphasis].

But then we started to think through what Mr, now Professor Pascoe was saying in Dark Emu and we have come to the conclusion that, once again, Professor Pascoe is manipulating the meaning of a word, in this case the Eurocentric word ‘democracy’, to use it to encompass an aspect of Aboriginal culture for which it is totally inappropriate.

Let’s look at how three Elders might view the Law in Aboriginal society, its power and whether societies individual members have a say, or a democratic vote, in who gets to exercise that power.

A Tale of Three Elders

Elder Number 1 - Bruce Pascoe, Aboriginal Elder

Aboriginal Elder, Professor Pascoe

In the Chapter in Dark Emu, THE HEAVENS, LANGUAGE, AND THE LAW, Professor Pascoe writes,

‘There is no doubt that Aboriginal life was not one long dream of peace and harmony. Anger, bitterness, betrayal, revenge, and punishment were all common, but they were governed by strict rules. The violence was often punishment enshrined in the execution of law, the tried and true systems of cultural, social and religious maintenance.

It’s difficult to look at the decision-making processes involved in the creation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island government and not think of the word democracy. Were the Elders elected? Not all who became old were included in the final decision-making processes; that authority was received following the complex trials of initiation.

To that extent, Elders became the equivalent of senior clergy, judges, and politicians. Their role was codified by levels of initiation that elevated them to a position where they could influence particular areas of policy. Their election to that position was gradual and complex, usually through the initiation process, but they didn't assume that position by force or inheritance. They earned the respect of their fellows. All other processes of delivering justice, protecting the peace, managing hierarchy and social roles as well as the dividing up the land's wealth were defined by ancestral law, and interpreted by those chosen as the senior Elders.

Of all the systems humans have devised to manage their lives on earth, Aboriginal government looks most like the democratic model. For a model to remain sufficiently coherent and flexible, and appeal to a large population spread over a large area for a lengthy period of time, requires our serious regard. It must have appealed to the vast majority of Aboriginal Australians as having an internal logic and fairness; otherwise it could not have survived.

The social cohesion arising out of this system of government allowed people to cooperate in all aspects of food procurement. Large numbers of people could gather to contribute the massive labour involved in the construction of dams, fish traps, and houses, and in the preparation and maintenance of croplands. Without political stability, activities extending beyond language and cultural boundaries would have been impossible’. (ibid., p186 - 187) - [our emphasis].

Professor Pascoe’s claim that because the Aboriginal ‘democratic’ model survived a ‘lengthy period of time’, ‘it must have appealed to the vast majority of Aboriginal Australians’. One could presumably say the same thing about slavery, which has been with us (and still is in parts of the Islamic world) for millennia, until the British started the long-process of its abolition. I am not sure even Mr Pascoe would agree that slavery, due to its long survival, ‘must have appealed to the vast majority of slaves’.

In this post we will ‘speak to’ Professors Pascoe’s assertion that pre-colonial Aboriginal society was ‘democratic’ and ‘requires our serious regard’, by looking at how Aboriginal ‘democracy’ worked on the ground in the society of the Tiwi Islanders on Bathurst and Melville islands in the Northern Territory. We will see if the Aboriginal ‘democracy’ there met the definitions of what Australians ordinarily think of as a ‘democracy’, the ideals and benefits of which our Australian Parliamentary Education Office explains are,

‘A democracy relies on the participation of citizens. They participate not just by voting, but by getting involved in their community… A democratic society is one that works towards the ideals of democracy:

Respect for individuals, and their right to make their own choices.

Tolerance of differences and opposing ideas.

Equity—valuing all people, and supporting them to reach their full potential.

Each person has freedom of speech, association, movement and freedom of belief.

Justice—treating everyone fairly, in society and in court.

There are ways to resolve different views and conflicts peacefully.

Respect for human dignity.

Equality before the law.

Safe and secure community.

Good government that is efficient, transparent, responsive and accountable to citizens.

Ability to hold elected representatives accountable.

Professor Pascoe is a modern-day Aboriginal Elder, someone who, as he states in Dark Emu, after the necessary ‘initiation’, could be expected to be viewed as an ‘equivalent of senior clergy, judges, and politicians’ whose ‘role was codified by levels of initiation that elevated them to a position where they could influence particular areas of policy’.

Elder Number 2 - Francis Gsell, Australian Catholic Elder

Francis Xavier Gsell, OBE (30 June 1872 – 12 July 1960) was a German-born Australian Roman Catholic bishop and missionary,

Francis Xavier Gsell, OBE (1872 – 1960) was a German-born Australian Roman Catholic bishop and missionary, who began active missionary work in Papua in 1900, then in 1906 re-established the Catholic Church in Palmerston (now Darwin), Northern Territory. He then established an Aboriginal mission in the Tiwi Islands (on Bathurst Island) in 1910-11 and worked there until 1938.

In his 28 years amongst the Tiwi people he was well placed to see how their Aboriginal version of ‘democracy’, such as it was, functioned, given that the Tiwi were still largely living their traditional, pre-colonial life with all its laws, customs and beliefs intact.

Unfortunately for Professor Pascoe’s theory where he claims that,

‘Of all the systems humans have devised to manage their lives on earth, Aboriginal government looks most like the democratic model…[and] requires our serious regard’,

we instead find that the writings of Bishop Gsell provide evidence which would make most modern Australians shudder at the traditional ‘democratic’ practices of the Tiwi people.

Bishop Gsell, who one would describe as an ‘Elder’ of Australian society, describes a Tiwi island democracy that, to us nowadays, looks decidedly ‘un-democratic’ and which would only ‘require our serious regard’ not to introduce into modern Australian society.

In his 1956 book, The Bishop with 150 wives , Bishop Gsell writes,

‘All authority [of the aborigines] derives from the fundamental laws and customs established by the great ancestor, and these are transmitted orally. They are unchanging, like the Ten Commandments. Nothing is modified; nothing is either suppressed or embellished, the result being that since all are equal before the law without discussion, a formidable theocracy is in practice a democracy.

No one can introduce a new law; no one dare suspend an old one; all that is permitted is interpretation, a power common to all adults. Thus there are no chiefs or kings amongst the aborigines as we have learnt to consider such amongst native tribes. Each aboriginal man can affirm, I am the Chief'; I am the King'', accepting without embarrassment the title sometimes given to him in ignorance by white men’.

Although all have the status of kings, none are born members of what might be called the Supreme Council. Membership of this is reserved for those who have braved and successfully passed through the rites of initiation, rites which may extend throughout years. Step by step, the candidate for this supreme honour approaches its threshold and it is unlikely that he will be invested with office before the evening of his life. The Supreme Council is, in fact, the Senate and, as will be guessed, all power and prestige is enshrined in the aged while the young men are undergoing their training…

In actual fact, the social system of the aborigines is communism, not the diluted form practised as a political system in parts of the world today, but an integral, absolute communism. Thus, if anyone with any faith in communism as a practical system of government wants to see demonstrated what communism really leads to, he could not do better than to live for some time among my aborigines to study their lives and habits. I am certain he would return cured of his illusions.

As the aborigines say, they are all 'on the same level', which may be translated: equal; there are neither high nor low, rich nor poor, neither master nor servant, no bosses and no employees, no bourgeois or proletarian, noblemen or slave, neither powerful nor weak. All are hunters; all are warriors; all are kings. None cultivate the land: therefore none is productive. All live on the same spoils of the chase, day after day, week after week year after year. All are ready to defend their own area as all are ready to invade their neighbours' territory.

Private property is unknown amongst them because everything belongs to everybody without exception unless it be, to a certain extent, their wives and their weapons. The children belong to the tribe, the game to the successful hunter.

However, it must be noted that in this republic all power is concentrated in the hands of the elders. They form the 'party' in European communist parlance, and all outside the party- the women, the children and the non-initiated-do not count. They have no say in any matter whatsoever, and their masters, “the party'', may dispose of them freely, even of their lives. (ibid., p28,29 & 32) - [our emphasis].

So, in Bishop Gsell’s opinion, Aboriginal society was a theocracy governed by unchanging Law, and only ‘democratic’ in the sense that all elder fully initiated men were equal before this Law. He also sees it as a communist society and, as we all know in communist societies, ‘everyone is equal, but some are more equal than others. In Tiwi society, ‘the party’ is as Professor Pascoe describes, a small group of initiated Elders, all men who hold power over all the others - the women, the children and the non-initiated men.

This is not the democracy of 21st Century Australia, where our franchise is open to all adult citizens, men and women.

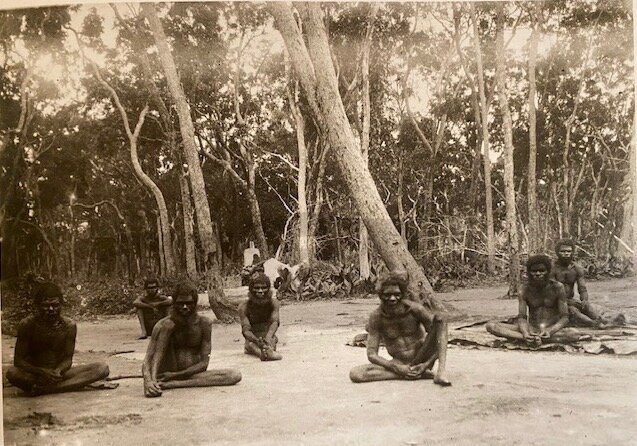

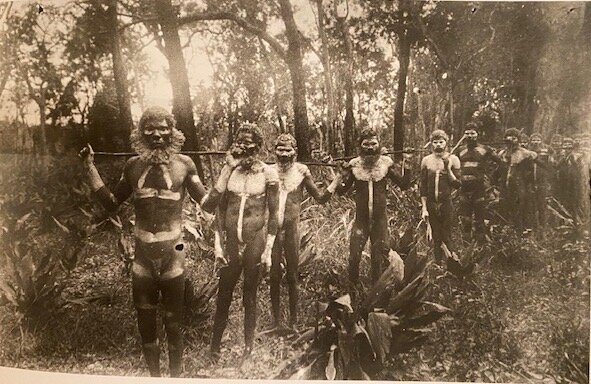

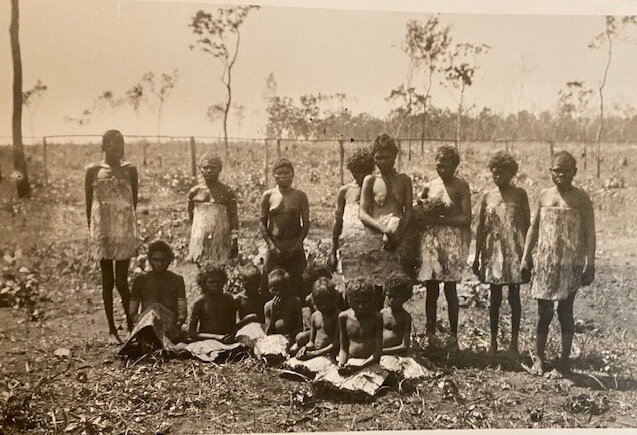

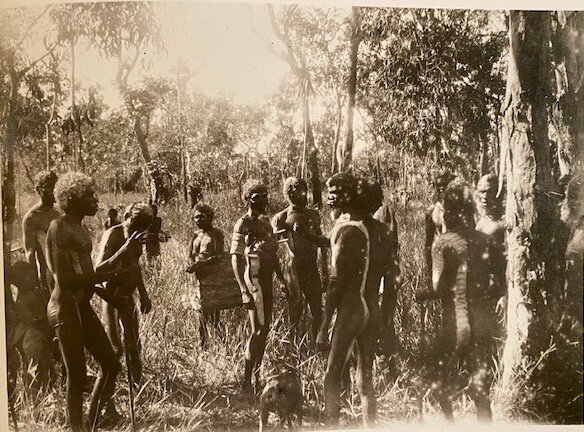

Below : Images of Tiwi Elder men (1 & 2), Tiwi women with characteristic paperbark skirts (3) and mixed group (4)

Once Bishop Gsell had established his Mission, the Tiwi men slowly began to visit and, after finding that the missionaries were friendly, they started to bring their wives and children. Gradually over time the parents developed a habit of allowing their children to remain in the mission, which Bishop Gsell describes,

‘These little ones were enormously interested in everything as this unsuspected world opened before their eyes - buildings that were built to last more than few days, the gardens that produced fruit at our command, and the strange mysteries that might be hidden in the church and the school.

A number of Tiwi boys decided, after much negotiation with their parents, to remain permanantly with the missionaries and were subsequently baptised as Christians. Once the nuns arrived at the Mission, the number of young Tiwi girls wanting to remain within the mission increased. But as Bishop Gsell recorded,

‘…everything was very different with the girls : because for countless ages tribal tradition has placed them in a very different position from the boys. The traditional matrimonial system deprived female a priori of the right to have any say in their future…[and resulted] in little girls who had hardly reached puberty ( ten or twelve years old) belong[ing] to a husband who was much older…[T]he older a man got, the more wives he might have : indeed he might have as many as twenty-five…It was always to me a sad sight to see these poor little mites of from eight to ten years becoming the playthings of old grey-beards whose other older wives too often made them the drudges while he, himself thought nothing of making them the object of shameful trading…

When eventually [the girls] were allowed to make short stays at the Mission, something that pleased them very much, hope grew in my heart; but when all seemed to be going well with a particular girl, some old chap would emerge from the forest to claim her as his prey. With tears in her eyes she would leave us. Of course she would come back; but each time she, and others in their turn, were taken away, their fate like a cruel stab from a dagger. (ibid., p77-79).- [our emphasis]

Bishop Gsell includes this juxtaposition of two photographs in his book for dramatic effect to illustrate to his readership the confronting nature of Aboriginal bride bestowal.

The subtitle reads,

‘The old man of the tribe discussing the disposal of…….his wife.’

Although the child in this photograph is only very young and will have no understanding of what is happening with regard to her future, the situation would have been potentially much more traumatic for a girl who had just reached puberty. We cannot presume that in all cases the very young girls did not want to leave their families to become young wives to older men, but one just needs to watch a modern day tribal marriage as a proxy for how traumatic and unwanted these marriages must have been for some girls. And they didn’t have any say in their future - No Vote for You! - how ‘undemocratic’!

This state of affairs continued for a number of years, with Bishop Gsell unable and unwilling to interfere with the custom taking of the young girls from the mission to be the wives to the Elder Aboriginal men. Bishop Gsell makes the comment in his book,

‘Must this go on for ever? I asked myself. The present was surely overcast and the future hidden in mist. Well, it was up to God to act. His time had come.’ (ibid. p79).

It was to take another 10 years before, in Bishop Gsell’s eyes, ‘God acted’.

Elder Number 3 - A Tiwi Elder Man

In 1921, Bishop Gsell writes,

‘There came to me a hairy anonymous [Tiwi Aboriginal] man who said, “I have come to fetch my wife." 'And who is your wife?'' I asked. “That one,'' he said; and he pointed to Martina’ (ibid., p80).

Bishop Gsell tells us that Martina,‘belonged to the Maolas tribe and she came from the north of the island’ and was an ‘intelligent, lively little girl and quite clever at small tasks’ (ibid., p80). She was about 10 years old at the time and was being claimed by a husband who was probably around forty.

Tiwi man, Melville Island, Northern Territory, 1911-12. Perhaps like Martina’s promised husband. Photo credit: Baldwin Spencer

Young Tiwi girls in class ca1920 perhaps similar to Martina - Source: MSC Archives, Kensington

Tiwi (Bathurst Island) men -Source Internet

One of the ‘promised husbands’ Source: MSC Archives, Kensington

Bishop Gsell continues,

‘Nothing could be done, I knew. No one might challenge the law of the tribe. No one had ever thought of doing so. Martina…must go with this hairy, anonymous man and be lost in the sad company of the tribal women, slaves, owned body and soul by the men of the tribes. One might not try to persuade, to beg a reprieve for this bright little one whom we loved.

But now a most extraordinary thing happened. Martina said, ''No,I will not go with that man”.

I am astonished, and to myself I say, "But the little one may not resist the tribal law. It is terrible, but she must go with this man and I, can I help her? Can I fight this man with my hands? Can I resist a strong custom of these people? I cannot. Yes, Martina must go."'

But now Martina comes near me and as her little fingers clutch my cassock she cries, “Oh, help me, Father. Do not let me go. I do not want to go with this old man who is ugly. Please, I want to stay at the Mission, and then I will be a Christian. Please, Father, let me stay!'

There is nothing I can do, nothing. I had always found it very hard to part with these little ones when men came to claim them. Now it is harder; it is harder because of Martina's courage. Also, she appeals to me for help, but what can I do for the poor child?

“Martina”, I say, “you must know that if I try to keep you here, this man can make very much trouble for you and, yes, for the Mission. And so you must go; you must go, because the law says that you must go…”

And so the little one accepts her fate and, trying to stifle her sobs, she goes with that man to begin a life which, I know, has less joy than that of the lowest beasts of the forest.

The incident passes;..But in five days' time Martina is back. The man has taken her to his district, more than forty miles from the Station; but she has not marched willingly, nor on arrival amongst his own people and, doubtless, other wives, does she show that submission a woman must show. She has resisted her man and he has driven a spear into her leg to drive a right spirit into her small body; and then, when it was dark, she has escaped and, despite the gash in her leg, she has come swiftly back to the Mission’ (ibid., p81).

When an ‘ugly mob of muttering, gesticulating tribesmen’ arrives at the mission and wanting to claim her back, Bishop Gsell then has a unique idea. He invites the men to make camp on the understanding they will discuss Martina’s return the next day. In the morning, he laid out on a table, a good blanket, a sack of his best flour, a good sharp knife, a hatchet of good-quality steel, a mirror, a handsome teapot, some gaily coloured beads, a pipe and some good tobacco, some yards of brightly patterned calico, some tins of meat and pots of treacle, all worth perhaps two pounds sterling.

Bishop Gsell tells us that traditionally the Tiwi husband would,

‘lend Martina to any unscrupulous brute who may desire her; but they will lend her only; they will not sell her. There is no question, ever, of giving up a woman who is useful as exchange for tobacco, four, tins of meat and pots of sweet treacle. Yet I must try, and I must not fail.” (ibid. p83).

Bishop Gsell then describes what happens when he makes the following offer to the men,

“All [of the goods] is yours to take away with you but, in return, you must let me have the girl you have come for.” The men are struck dumb with astonishment, and a deep and signifcant silence follows as they gaze at each other with open mouths...Clearly, they are tortured by overwhelming desire to possess such riches; but my price, as I well know, is one they fear to pay…The sale outright of the girl is in direct opposition to their tribal customs which have the force of law; and they can be severely punished by their tribal elders if they make this bargain…’

Much discussion occurs amongst the men, during which Bishop Gsell suspects that they will have,

‘to find a way of solving their difficulty, some way whereby they may sell the girl to me in exchange for my goods and still be able to placate their living elders, old, powerful men as frightening as the ever present spirits who also take a malignant interest in law-breakers.’

Bishop Gsell then writes that finally,

‘there comes to me that hairy anonymous old man who claimed Martina as his wife, quite justly according to native law. His face seems slit from ear to ear in a grin as he approaches. “Everything is good he declares happily. “We sell the girl but there is a condition: you must keep her for yourself always; she must not be passed on to any other man.”

This condition, a fig-leaf to cover their shame before higher ghostly powers, seems not a hard one to me although I do not accept it, something their eagerness to possess the goods allows them to ignore, for I merely say, “I am glad that you decide to sell. Take everything, and I’ll take the girl.” (ibid., p85-86).

Martina remained at the mission and when she reached the marriageable age of 18, it was understood she was at perfect liberty to accept, or to refuse, a proposal of marriage from any of the young men at the Mission. When she eventually chose a young man named Agau, who was about her age, and married him, that ‘was something that no young native woman in that part of the country had ever been able to do before. (ibid., p87)

So, Martina was only allowed to express her agency and gain some ‘democracy’ over her own life by resisting an Aboriginal ‘Law’ that meted out violent punishments, such as the spearing of a child like Martina in the leg because she refused to marry the old man allocated to her.

Professor Pascoe says this ‘violence was often punishment enshrined in the execution of law, the tried and true systems of cultural, social and religious maintenance.’

And Professor Pascoe says this Law, ‘requires our serious regard’.

No dear Professor, this aspect of Aboriginal law does NOT require our serious regard and it should be condemned as serious breach of human rights.

There is a reason why Australians have made ‘Forced and Early Marriages’ a serious crime in Australia.

This table shows the details of the first 14 girls ‘bought’ by Bishop Gsell as part of the ‘150 wives’ that he eventually ‘buys’ to release from their oppression by the older men.

So, as far as we can see, the lives of young Aboriginal girls in Tiwi society was one of serious oppression and totally unacceptable in modern Australia.

The only real beneficiaries in Professor Pascoe’s, ‘Aboriginal Democracy’ appear to be the fully initiated, Elder Aboriginal men, a class that one would think Professor Pascoe might himself belong to. Is that perhaps why he would favour our ‘serious regard’ in reconsidering this system of governance in modern Australia?

Further Images from Griffith University Bathurst Mission

Girls, Nuns and Peter de Hayr Source: MSC Archives, Kensington

Bathurst Island mission residents with Bishop Gsell, mission superintendent Fr. John McGrath, Br. Carter and ‘Old Peter’ Pierre de Hayr, 1939. Source: NAA Series M10, 3/34

Bathurst Island Mission - ca 1915

The school at Bathurst Island ca 1920 Source: MSC Archives, Kensington

Bathurst Island Mission - ca 1915

Further Reading and References

Publication on the history of The Tiwi with some further alternative views on Bishop Gsell.

Bathurst Island Mission, Griffiths University

Franklin, James, The Missionary with 150 Wives, Quadrant Magazine, 1st July 2012

George Orwell, in Essays - Politics and the English Language (1946) :

"The words democracy, socialism, freedom, patriotic, realistic, justice, have each of them several different meanings which cannot be reconciled with one another. In the case of a word like democracy, not only is there no agreed definition but the attempt to make one is resisted from all sides. It is almost universally felt that when we call a country democratic we are praising it : consequenly the defenders of every kind of regime claim that it is a democracy, and fear that they might have to stop using the word if it were tied down to any one meaning. Words of this kind are often used in a consciously dishonest way. That is, the person who uses them has his own private definition, but allows his hearer to to think that he means something quite different.