Aborigines relied upon Mythology, not Agronomy, for the maintenance of their food supply

In 1940, the Australian anthropologist, Dr C.P. Mountford, lived with the Pitjandjara in the Mann Ranges in central Australia and studied their art, myth and totemic geography, the results of which he published as, Nomads of the Australian Desert, in 1976 (1). The Pitjandjara at that time were almost untouched by European culture and still lived their traditional lifestyle.

A main theme evident throughout Nomads of the Australian Desert, is that the Pitjandjara led a completely nomadic, hunter gatherer lifestyle, with no sign whatsoever of what we would call agriculture, such soil tilling, cultivation, domesticated seed selection, irrigation, regular large food storage, animal husbandry or the construction of permanent houses. This is despite the fact that their lands were near Mr Pascoe’s, ‘Aboriginal Grain Belt’, a seed-grass producing area that Mr Pascoe suggests is evidence for aboriginal agriculture. Indeed, Mountford provides a quote in the Introduction of his book that summarises the fact of life for the Aborigines :

“Australia possesses no milk-producing animal that could be kept in domesticated herds and flocks for food purposes. It possesses very few fruits of much value and only a single nut now used in commerce and, with perhaps one exception, no vegetable that has passed into the common service of the white man. In the central parts of Australia grains of various grasses were used but none of these is likely to be capable of cultivation as crops. Roots, similarly, such as the yams of Ipomoea, have not been brought under cultivation and hardly hold out much promise if this were attempted. Thus the animal and vegetable surroundings of the first-comers to Australia were singularly unfavourable for the development of a pastoral or an agricultural people. In fact such knowledge as they might have possessed in regard to these matters before their arrival [on the Australian continent] could have been of little or no use and must have been quickly forgotten from want of application. Thus they became essentially nomads, forever hunting and seeking after their daily food. It was only in areas where fish or game, for instance, were abundant that the population became to some degree stabilized. Even here there was no attempt to cultivate food plants.”

– Mountford quoting, Cleland, J.B. The Ecology of the Aboriginal in South and Central Australia, in Aboriginal Man in South and Central Australia, Part I, British Science Guild Handbook, 1966, p 113.

Mountford therefore, is another example of a highly qualified anthropologist, who has studied Aboriginal society in great detail, who does not support Mr Pascoe’s theory that Aboriginal society was a settled, agricultural one.

Mountford provides extensive detail into the mythology that the Pitjandjara practiced to “increase” the amount of animals to hunt, and foods to gather, within their lands. Except for the occasional use of fire, they did not use what we would term agriculture (that is, human intervention and techniques to directly influence the supply of foodstuffs, such as soil and crop cultivation, seed selection, irrigation, animal breeding and husbandry) to manipulate plants, animals and the environment, so as to increase yields and the supply of foodstuffs.

Instead, Mountford explains, the Aborigines relied upon the life-essence, kuranita, to increase their food supplies :

“My [Pitjandjara] informants explained, however, that, even though the tjukurita [the creation period] men and women were no longer alive, each of them had left behind, wherever they had performed any task, a mysterious and inexhaustible supply of a life-essence, kuranita, which is peculiar to its creator. At certain of these totemic places, known as pulkarin, a ceremony, performed by Aborigines, will cause that particular kuranita to leave the totemic centre and, rising into the air like a mist (an Aboriginal explanation), impregnate the particular plant, tree, or natural force, with which it is associated, thereby increasing its supply. There are many of these pulkarins (called “increase centres” in this study) through-out the country of the desert nomads.” – Mountford, ibid p53.

Instead of an Aboriginal agricultural society that prepared the soil, planted seed and cultivated a crop, as Mr Pascoe suggests from his reading of colonial journals, Mountford, an anthropologist who actually lived with the nomads of central Australia, found that Aborigines relied only on “increase rituals” as a way of ensuring a regular food supply.

“During the time of creation [there were] four mulga-seed men Windimina, Windulka, Jininpulta and Paralpa…One day while collecting mulga-seed Windimina became ill…[and] collapsed on the ground and died. On the place where he once stood is a single mulga tree, and his body is a pillar of rock. Some time later the other three [Mulga-men]…also died and their bodies were transformed into boulders”

- Mountford, ibid, p139

The Aborigines distinguish four different kinds of mulga-trees, each arising for their respective Mulga-men, windimina, jininpulta, paralpa and windulka, and each species has its own “increase centre” comprising of boulders.

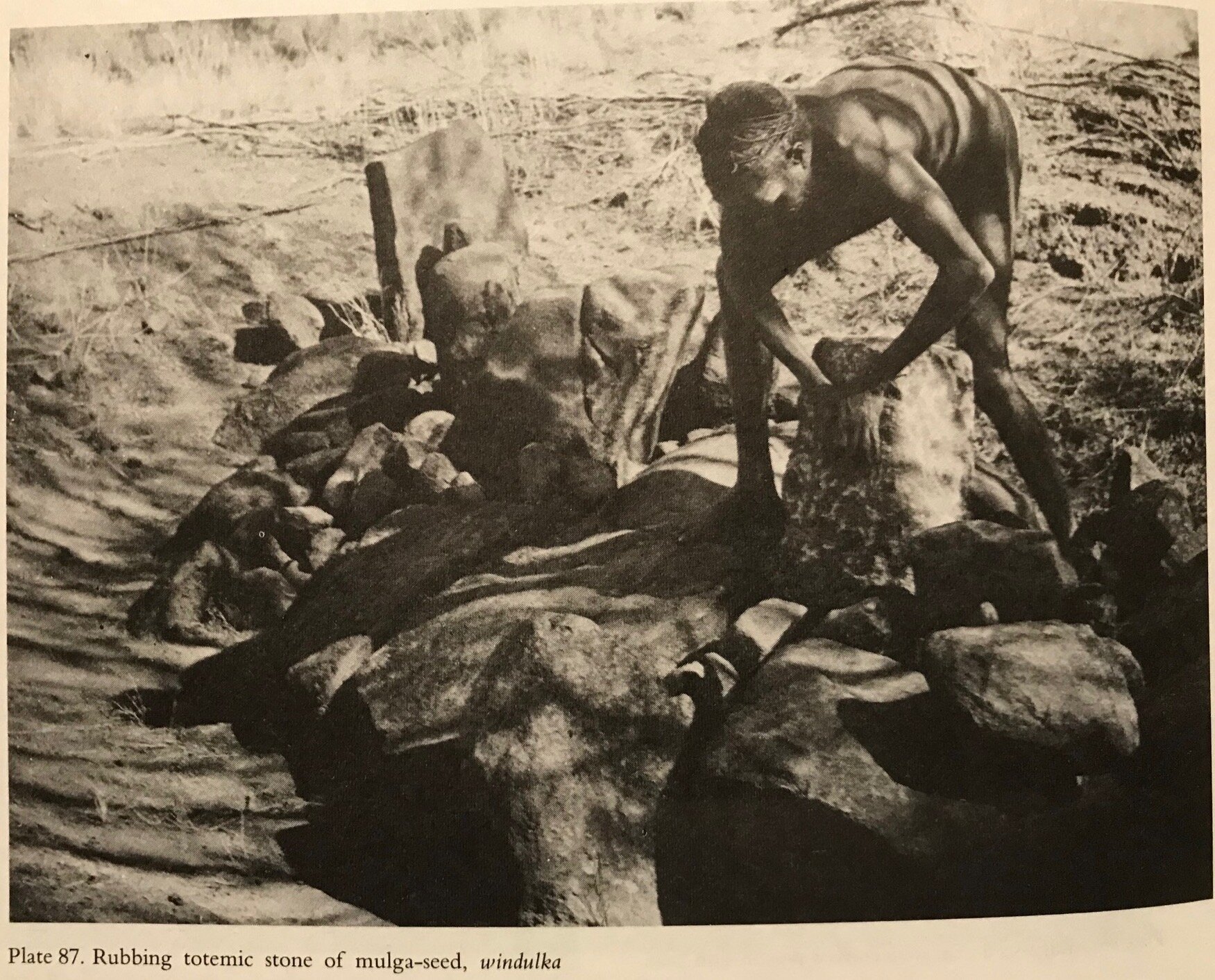

The increase rituals, comprising rubbing of the stones and chanting, are performed at the correct time of the year releasing from the totemic stone the relevant life-essence kuranita, which, flying into the air, would cause each specific mulga-tree to bear more seed.

Mountford describes the ritual as follows;

“My informant, Tjanjundina…rubbed the upright mulga-seed totemic stones with a boulder of travertine. Then, puncturing his sub-incised penis, he allowed the blood to fall on the top of each one in turn. The Aboriginal then lightly rubbed a low flat boulder, which belonged to the windulka mulga-tree, with another stone, explaining at the same time that if he used too much force when rubbing this stone, the seeds would grow so large and tough that they would have little food value. All the time that these increase rituals were being performed, Tjanjundina chanted [translated] … ‘south - grow up; west - grow up; east - grow up; north’. The literal translation of this chant is the instruction to the mulga-trees “all over the world” [this means, of course, the people of the desert nomads] to bear much seed.” - Mountford, ibid p139.

One can completely understand now why the Australian Aborigines did not develop agriculture. Agriculture requires a mental capacity for agronomy - the applied science and understanding of soils, cultivation and crop production that comes from human agency. The Aborigines put their human effort into their rituals to bring forth the ‘increase’ powers of their totems. It did not occur to them that they, as humans, should intervene to increase the yields of, for example, mulga-seed by planting mulga-seeds in good soils and watering the seedlings to create large mulga-tree ‘orchards’ from which much larger quantities of seeds could be harvested.

“Although kuranita is concentrated in specific localities for maintaining or increasing certain foods and other necessities, it is diffused throughout the whole country of the desert nomads. Everything that the Aborigines see about them, the hills, the watercourses, the trees, the heavenly bodies, and even, in some places, the grass between the boulders has been created by some tjukurita being, and is impregnated with kuranita. The creatures, too, possess this same life-essence…Blood is also regarded as kuranita, and the lavish giving of it to a youth, particularly during his initiation rituals, is looked upon as a gift of life-essence from the older to the younger man, so that he will grow up to be strong and healthy.” - Mountford, ibid p53-54

Now, in absolute terms, this use by the Aborigines of ‘mythological increase centres’, rather than ‘human intellectual agronomy’ to ‘produce’ food is neither good nor bad, right nor wrong, but it is just the path that Aboriginal society took. It is not for us in the 21st century to condemn or denigrate Aboriginal society for taking this path, but we are completely entitled to discuss the outcomes of these decisions in a scholarly way. Indeed, there are fascinating arguments that will be explored in other Dark Emu Exposed blog posts that will show that some great advantages accrued to Aboriginal society for NOT taking the ‘human intellectual agronomy’ path, which ultimately would have led to ‘settled agriculture’.

‘When it is time for the increase ceremony of honey-bearing blossoms the Aborigines travel to Palanja. There the men re-arrange any displaced stones [of this increase site]…send the women away..and [t]he ceremony begins…The men open the veins in their arms…and allow the blood to fall on the stones…All the perfomers…eat the coagulated blood of the opposite group [of performers]…On asking the men why they poured their blood on the stones…, one of the older men gave me a visual demonstration of the belief. Taking a sharp twig he punctured the urethra of his sub-incised penis and allowed the blood to drop on the rocky surface. He then explained that when a small amount of human blood (being the same colour and bearing the same name, jandi, as the honey in the tree-blossoms) fell on the pile of stones…this blood acted in somewhat the same manner as a catalyst. It caused the kuranita of honey contained in the stones…to diffuse into the air and settle on all the honey-bearing trees. This would ensure that ‘everyone in the world’ would have an ample supply of this delicacy” - Mountford, ibid. p283-291

The Aborigines relied on spiritual rites, such as ‘scraping bark from [a] tree to increase [the] supply of kalka-kalka grass seed.’ (Mountford, ibid, plate 343).

The Aborigines believed that this was a valid method of food production as they were a deeply spiritual, hunter-gatherer society who did not believe they could “produce” food by their own human agency. If they were a settled agricultural society, as Mr Pascoe claims, Mountford would have instead taken photographs showing Aborigines tilling the soil, digging irrigation ditches, building granaries and stacking hayricks.

(1) C.P. Mountford, Nomads of the Australian Desert, Publisher Rigby, 1976.

Alistair Crooks has written that Pastor Paul Albrecht of Hermannsberg Mission as said,:

“The fact that no Aboriginal land-owning clans have chosen to return to a traditional life of hunting and gathering — a situation made possible for a number of clans in the Northern Territory with the passage of the Northern Territory Land Rights Act 1976 — would indicate that no Aborigines want to return to a traditional way of life.”

‘And why should they return to those old practices? As Pastor Paul Albrecht has also pointed out, for traditional Aborigines,’

“the correct performance of certain rituals, was the means of production. It was the ritual which produced what the various clans needed to live on. This was then gathered, and the kinship system provided the mechanism through which this production was allocated and distributed to individual clan members.”

Remote-area Aborigines are freed from the need to perform those “certain religious rituals” themselves…by the availability of the endless harvest of the white people’s “increase ceremonies”.

‘They are also freed from the drudgery and uncertainty of the actual hunting and gathering part of their daily routine, and similarly liberated from the need for a perpetual cycle of nomadism in search of game, by the presence of a constant centralised food supply at the local supermarkets'.’