Dr Liz Conor - A Nominee for The 2020 Bruce Pascoe Award for Selective Photo Editing?

Liz Conor is an ARC Future Fellow at La Trobe University.

She is the author of Skin Deep: Settler Impressions of Aboriginal Women, [UWAP, 2016],

a ‘book…long in the making, over a decade. By its nature any tracery of racism and misogyny can only be written through with regret. [sic]

What it documents necessitated the utmost deliberation.’

- from the Acknowledgement’s page of Skin Deep.

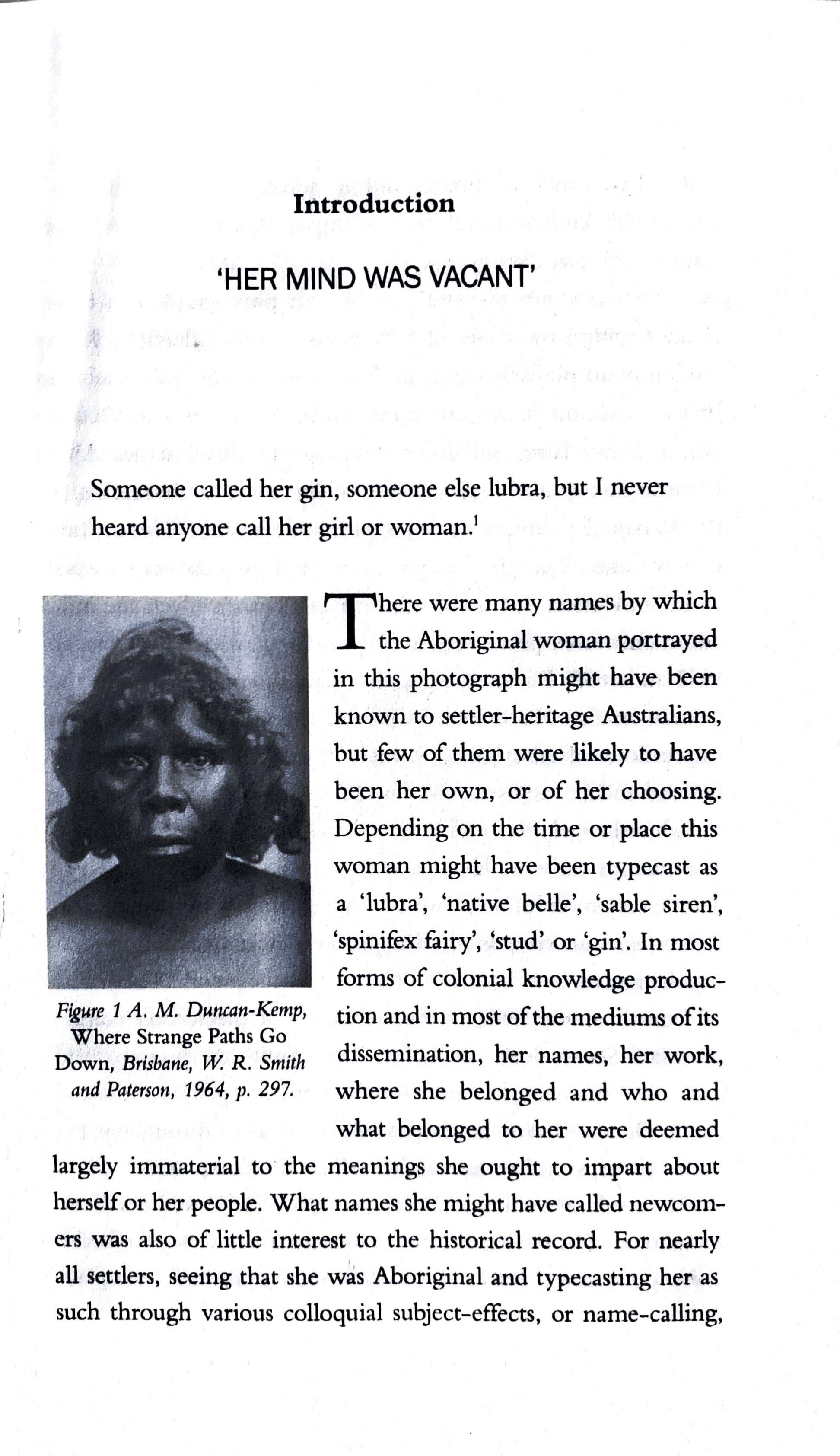

On page 1 of her book, Skin Deep, Dr Conor opens with a quotation from Norman Laird (Footnote 1),

‘Someone called her gin, someone else lubra, but I never heard anyone call her girl or woman.’

and then she launches into her text,

‘There were many names by which the Aboriginal woman portrayed in this photograph might have been known to settler-heritage Australians, but few of them were likely to have been her own, or of her choosing.

Depending on the time or place this woman might have been typecast as a 'lubra', ‘native belle’, 'sable siren’, ‘spinifex fairy,' stud' or 'gin'.

In most forms of colonial knowledge production and in most of the mediums of its dissemination, her names, her work, where she belonged and who and what belonged to her were deemed largely immaterial to the meanings she ought to impart about herself or her people.

What names she might have called newcomers was also of little interest to the historical record. For nearly all settlers, seeing that she was Aboriginal and typecasting her as such through various colloquial subject-effects, or name-calling, sufficed to evoke an understanding about her, one as surface-based, half-knowing and compelling as this image: a way of knowing that was skin deep’.

The encounter encapsulated by this photograph was experienced within the pages of a hardcover, now collectible, 1960s edition of an outback woman's 'life among the blacks' (Footnote 2) - a book in the tradition of better-known authors such as Mrs Aeneas Gunn, Daisy Bates and Mary Durack. In this instance Alice Duncan-Kemp gives an account of life on a cattle station in the Channel Country of Southwest Queensland. The caption merely states,

‘This photograph was taken during the early days of white settlement.'

It has the shimmer of albumen silver, the most commonly used processing technique for photography between 1857 and 1895. For over a decade I have attempted to trace the woman in this photograph as part of this study of settler print impressions of Aboriginal women, to repatriate her image to her descendants and seek their permission and cultural clearance. Visual anthropologists and curators of Aboriginal family history in museums and state libraries and public record offices…have never seen this image before. The family of Duncan-Kemp believes the publishers of the second edition of Where Strange Paths Go Down, W.R. Smith & Paterson, held a number of such photographs of Aboriginal people unrelated to the Duncan-Kemp station and scattered them throughout her book, perhaps against her wishes.

Duncan-Kemp wrote about the Karuwali, Marrula and Mitaka peoples. Like Bates herself and the photographs she sometimes even misattributed to people she claimed to know, Paterson may have used a postcard, or a plate cut from a book, or bought it from a studio as a print, though the quality suggests he had a good print and perhaps the original.

In settler-colonial Australia this woman had long been type-cast under already established, even entrenched, conventions for knowing Aboriginal women. From the 1790s around Sydney, she was known as a 'gin', and from the 1830s around Tasmania and then into Victoria, a 'lubra'. The failure to credit her own name was an erasure of her identity - at least from the settler perspective.

Other categories were called upon to construe her meaning, in a process of what we might call cultural captioning. Her photographed image evoked recurrent meanings of Aboriginal femininity for white consumers through the machinery of print, namely through its repetition…As I have explained elsewhere, 'lubra was quite possibly a misinterpretation..[of a] local [Aboriginal] word for penis as referring to wife. Lubra became a settler construct that spread through the settler imagination with alacrity, sweeping aside local language use, totemic distinctions, restricted nomenclature, mortuary protocol and permissible forms of address.

All Aboriginal women become lubras, whether they were married or not.

Very often this classified them with the social phenomenon of 'black velvet', that is, as a class of Australian women to whom sexual access was assured for settler men, particularly on the remote pastoral, mining and pearling frontiers - the 'stud' was said to be 'easy for the taking.

From this survey of white imaginings of Aboriginal women, the lubra type became a masthead of sexual and racial difference localised to Australia. And like terra nullius, despite being incorrect, it attained the status of a sustaining national fiction that absented the identities of Aboriginal women, or imagined them within a particular frame, or a sort of cultural skin. Since the photograph gives nothing away about the woman it takes as its subject, a kind of over-determined anonymity was imposed over her surface - skin, hair, expression - which then carried the burden of her meaning…In the colonial visual archives the pathos and beauty of this woman’s photograph make it a singular portrait. By my reading - and I take ownership of this as a subjective reading - it seems an expression rent, dissembled, and yet defiant. A scholarly response should couch it in the repertoire of meanings construed about Aboriginal women for white consumption since settlement, and this is certainly what this book will attempt. (ibid., p1-5.) -[our emphasis]

Footnote 1: Laird, N., ‘Aborigine girl’, Walkabout, vol. 12, no. 12, 1st October 1946 p20.

Footnote 2 : A. M. Duncan-Kemp, Where Strange Paths Go Down, Brisbane, W. R. Smithand Paterson, 1964, p. 297. [sic, see our copy of page 297?]

Something in Dr Conor’s analysis of a photograph of an Aboriginal woman, appropriated from a 1964 book, did not sit quite right with some of our staff here at Dark Emu Exposed; something smelt a little ‘Pascoey’. So, using skills we have honed on critiquing Mr Pascoe’s Dark Emu, we turned our attention to getting a little deeper into Skin Deep, the work of Dr Conor.

Where Actually is the Photograph?

What we found, when we opened our original copy of A. M. Duncan-Kemp’s, Where Strange Paths Go Down - a second edition copy, published in Brisbane by W. R. Smith and Paterson in 1964 - at page 297, as Dr Conor cites in her book, is not the photograph, but rather the following page:

Hmmm…what has gone wrong here with Dr Conor’s citation? The photograph, that she cites as the centre-piece at the opening of her book, is not to be found on page 297 of her reference as she claims.

We have the correct Second 1964 edition of the book, as confirmed by the author when she opens her Preface with,

"When it was decided to publish a second edition of “Where Strange Paths Go Down”….’

Here are the title pages below to confirm we seem to have the correct, 1964 2nd edition as cited by Dr Conor.

But said photograph of the Aboriginal woman is NOT on page 297, as claimed by Dr Conor.

And Dr Conor does it again when she cites as her, ‘Note #2’ in her Introduction, a phrase used by Duncan-Kemp, ‘life among the blacks', as being on the same page 297. We find that page 297 does not have the photograph, or the quote. It seems that all the ‘tracery’ of Dr Conor’s examples lead to the same, wrong page 297?

This could be just an inadvertent typographical error, which regrettably can happen in any scholarly work - or maybe, as we found with Mr Pascoe’s Dark Emu, it is a fore-warning of sloppy or fabricated research yet to come. We shall see.

A search of the whole 299 pages of A. M. Duncan-Kemp’s wonderful and heavily illustrated book, Where Strange Paths Go Down, finally locates the photograph cited by Dr Conor, within several illustration pages sandwiched between pages 286 and 287 (See below). So Dr Conor seem to have made a ‘typo’ - it should be ‘facing p287’ not ‘p297’.

But have a look at both the photographs on these two facing pages. On the left, is the star exhibit that Dr Conor has extracted for her book, a beautiful portrait with exquisite lighting of a young, intelligent, but pensive looking, Aboriginal woman, with the caption, as Dr Conor correctly cites,

‘This photograph was taken in the early days of white settlement’

But then dear reader, have look at the photograph on the right-hand page. Any viewer, even Dr Conor, looking at the photograph on the left could not help but see the photograph on the right at the same time. It is of a very young, beaming Aboriginal girl, presumably on a school excursion, seated in an imposing chair under a Commonwealth of Australia shield. The caption reads,

‘A Bright Lass of Today - Dolly Dimples, from Hall’s Creek, tries the Chairman’s Chair in the Legislative Council Chambers in Darwin.’

Photographs from a double-page of Duncan-Kemp’s book, Where Strange Paths Go Down.

Dr Conor just appropriates the left-hand photograph for her book Skin Deep; but what about the right-hand photograph of this ‘diptych’?

Duncan-Kemp’s Views on the Progress of Aboriginal People

On reading Duncan-Kemp’s book, we find that she believed that the best ways forward for Aboriginal people were of two paths.

One path was:

‘…guided assimilation; improving the younger members of the race by means of teaching, without breaking-off suddenly their age-old beliefs and ritual, and especially by personal contact with reputable white people (ibid., xxviii)…[where] ‘…the European community in general is facing up to its responsibilities concerning the future of the aborigines...(ibid., xxix)…‘The basic principles of assimilation must be consent, freedom, equality.’ (ibid., xxx)

The other path, for the remaining ‘myalls’ or ‘wild-blacks’, those Aboriginal people still living very much a traditional life, away from European influence, Duncan-Kemp suggested that:

‘[t]o the handfull of myalls that remain - a proud people - our plain duty is to reduce all intereference with their way of life to a minimum, regardless of how benevolent in design such projected interferencve may appear.’ (ibid., xxxi).

So, from our reading of Where Strange Paths Go Down, it is quite plain, even to us amateurs at Dark Emu Exposed, that these two photographs are juxtaposed for a reason. Duncan-Kemp (or perhaps her editor ?) chose the beautiful, even romantized, ‘vintage’ image on left to perhaps convey a sense of a proud, traditionally-minded, Aboriginal woman at ‘First-contact’, in a somewhat pensive mood as to what her future may hold, whereas the young, bright, Dolly Dimples on the right, seated in the most powerful chair in the Northern Territory, represented just what might be possible for Aboriginal women in realising their full potential in the future.

To our mind, these two photographs are to be a viewed as a pair - one only makes sense in relation to the other.

Now Dr Conor, has wrenched this photograph from Duncan-Kemp’s book from its contextual space as being representative of an Aboriginal ‘every-woman’, ‘during the days of early white settlement’, and installed her within her own book, and labelled her as a,

‘typecast’ ‘lubra’, ‘native belle’, ‘spinifex fairy’, ‘stud’ or ‘gin’.

In our view, this is a gross, unscholarly and over-sexualized distortion of what Duncan-Kemp wanted the two photographs to convey.

Those readers looking to Dr Conor’s book, Skin Deep, for an antidote to the harm they believe was caused by colonial Australia and its ‘white-supremacy settlers’, who supposedly ‘exploited’ Aboriginal women, might come to the conclusion that, ‘the more things change, the more they stay the same’.

Are white, privileged academics, funded by the settler-class, the new masters and exploiters of the ‘gins’ and their images?

So what of Dolly Dimples? Did she represent, as Duncan-Kemp seems to hope with her juxtaposed photographs, the Aboriginal ‘every-woman’ of the future?

Unlike the professional academic Dr Conor, we amateurs at Dark Emu Exposed decided to investigate further the right-hand photograph in Duncan-Kemp’s diptych, the future Aboriginal ‘every-woman’, Dolly Dimples.

Who was she?

This is what we have found so far.

On the 20th November 1957, the Australian Women’s Weekly published an article that contained a picture of a Dolly Dimples, from the Australian Inland Mission hostel at Halls Creek, swimming in Darwin whilst on a school, 8-day seaside holiday.

This Dolly Dimples looks very much like the Dolly Dimples beaming at us in the photograph of Duncan-Kemp’s 1964 book, with the caption,

‘A Bright Lass of Today - Dolly Dimples, from Hall’s Creek, tries the Chairman’s Chair in the Legislative Council Chambers in Darwin.’

Our readers will see from our transcription of the article’s text here that it is most certainly the same Dolly Dimples. Her photograph was included by Duncan-Kemp as a ‘bright lass’, who had the potential, and complete right, to aim for a ‘top-job’ within Australia society.

So there you have it.

In our view, Duncan-Kemp juxtaposed those two photographs of Aboriginal women - one representing the past, in the early days of white settlement, and one representing the potential future for Aboriginal women who chose to assimilate into mainstream Australian society - as a way of underlying her belief that these were the two best ways for Aboriginal people to live. To remain as isolated from European influence as much as possible, or to fully integrate, or assimilate, like everyone else into mainstream Australian society.

So was Duncan-Kemp right to be optimistic for the future of the Aboriginal ‘every-woman’, as represented by Dolly Dimples?

Well in fact she was. Unwilling to accept the victim-mentality that seems to be peddled by ‘virtue-signaling’, white, academic women safely ensconced in their Ivory Towers ‘down south’, many Aboriginal woman are getting on with their own lives very successfully to make our society a better place for themselves, their families and communities, and Australia as whole.

Within a generation or two of Dolly Dimples ‘seating’ herself in the NT Legislative Council Chambers of Darwin in 1957, a time when there were no Aboriginal members of the NT Legislative Council, there have now been 22 Aboriginal members of the NT Legislative Assembly, since 1974, when it replaced the Council.

To show just how far Duncan-Kemp’s, Aboriginal ‘every-woman’ as represented by Dolly Dimples, has come, consider the career of Bess Nungarrayi Price. Born and raised in a humpy at Yuendumu, she has battled against the odds, but managed to successfully work her way to the top of our society. She even became a member of the NT Legislative Assembly, fulfilling perhaps the dreams that Dolly Dimples and Alice Duncan-Kemp may have had all those years before.

US President Barack Obama, Bess Price and Julia Gillard meet.

‘On Monday, two US consulate officials flew from Melbourne to Alice Springs to see Warlpiri woman and newly elected Northern Territory MP Bess Nungarrayi Price.

For a while they talked Northern Territory politics, not that unusual a topic given Ms Price has long dealt with US officials and met US President Barack Obama in Darwin last year. The conversation soon took a surprising turn when they said they wanted to nominate her to become the first Australian woman to receive the US International Women's Courage Award’.

We ask our readers just for a moment to think about the symbolism of this photograph of Bess Price meeting together with US President Barack Obama and Julia Gillard.

Here was America’s first black President, from a British settler-country that had a significant history of black slavery, meeting with Australia’s first female Prime Minister, who was born in the United Kingdom, the country that initiated the end of slavery, and who migrated to settle in Australia as a child, nominating, for a US International award, a Warlpiri woman, recently elected to a Parliament based on the Westminster system, whose ancestors had been in Australia for 50,000 years. What a proud moment for Australian society and our shared British and Aboriginal heritages.

Dr Conor would have us believe in her book, Skin Deep, that today ‘racism and misogyny’ are rampant in Australia, with racism ‘embedded in the DNA’ of our nation.

What a load of rubbish - the evidence above speaks otherwise.

Thank God we are Nation of Dolly Dimples, Alice Duncan-Kemps and Bess Prices.