Ref 2: Professor Davis Book

This file contains the research notes and evidence to show that Professor Megan Davis and her family were mistaken to believe the follows claims that they made in relation to their Vanuatu ancestors, in particular their grandmother, Elizabeth Ober:

“Part of my family came to Australia via the practice of "blackbirding" – that is, the kidnapping and enslaving of South Pacific Islanders to work on plantations, especially in Queensland.”

- Professor Megan Davis, The Guardian, 16 May 2014

and

"My grandmother Elizabeth Ober was a South Sea Islander woman. She was taken and brought here from Vanuatu. They would basically kidnap people and brought them here to work in the sugar cane industry."

- Lucy Davis (Professor Davis’s sister) - see ABC excerpt here from about 2:18].

Elizabeth Ober was not kidnapped from Vanuatu as the Davis family claim. She was in fact born in Queensland to her two Ni-Vanuatu parents who had arrived on indentured labour contracts. She has a Queensland birth record (Figure 1).

Figure 1 - Birth Extract of Queensland Births, Deaths & Marriages Records for Elizabeth Ober (nee Woolangarty). Elizabeth, and her siblings, are registered under both parents first names as their surnames. Neither Woolangarty nor Booty had a last name.

Her parents were not ‘enslaved’ or ‘kidnapped’ but in fact had come on indentured contracts. Indeed both her parents, her mother Woolangarty (aka Mary) and her father Booty (aka Robert Ober) went back to their native islands on the expiration of their initial labour contracts, but that within a year or so they re-signed new contracts [or independently decided] to return to Queensland - hardly the choice of anyone who was ‘enslaved.’

The following evidence indicates that the Davis family’s South Sea Islander ancestors were not tricked, nor kidnapped by force, and enslaved in Queensland’s sugar industry.

Professor Megan Davis’s three great-grandparents, who were born in the South Sea Islands, and who subsequently came to Queensland as indentured labourers:

A) Wallangartie (aka Mary Marlo, wife of Robert Ober (Booty) below, and mother of Elizabeth Ober, Prof. Davis’s stated grandmother) who was born in 1853 at Malao, Sanma, Vanuatu, South Sea Islands and died aged 95 on 25 May 1948, Pialba(?) Queensland;

B) Tinwilligan or Tanwilligan (aka William (Billy) Willighan) who was born in 1856 in the South Sea Islands and died aged 80 on 5 November 1936 Maryborough, Queensland; and

C) Booty (aka Robert Ober) who was born in 1852 on Aoba Island, New Hebrides (central Vanuatu), South Sea Islands and died at age 81 on 24 November 1933 Point Vernon, Queensland.

The relative positions of these three South Sea Islander ancestors in the alleged paternal family tree of Prof. Davis are shown in the Family Tree excerpt below (see Figure 6).

Figure 2 - Excerpt showing two branches from the alleged paternal Family Tree of Prof. Megan Davis showing her three South Sea Islander ancestors. Download File.pdf here

The Actual Lived Experience of Wallangartie (aka Mary Marlo, wife of Robert Ober (Booty)

In 1946, a small news item appeared in the Entertaining section of Queensland’s Maryborough Chronicle. It described how the, Torquay Baptist Church had been,

‘… decked with bowls of clove-scented stocks, on a Monday afternoon, when the Torquay Baptist Ladies' Guild entertained The Rev. Edwards, President of the Queensland Baptist Union, at their 21st birthday social…’ (see Figure 3)

The reporter went onto describe that,

‘… there was a little aged coloured lady from Urangan, who remembered Mr. Edwards. She is Mrs. Ober, who is in her nineties, and mother of Mrs. Harry Davis, who does so much concert work for charities….Mrs. Davis very sweetly rendered “God Send You Back”,….’ (See Figure 4)

Figure 3 - Source: Maryborough Chronicle, 19 October 1946, p. 8

Figure 4 - Source: Maryborough Chronicle, 19 October 1946, p. 8

This ‘little aged coloured lady’ was the great grandmother of Prof. Davis - born in Vanuatu as Wallangartie, but who became known as Mary Marlo in Queensland and then Mrs Ober on her marriage to fellow Ni-Vanuatu man, Robert Ober (Booty) [see Note 3 below for spelling variations].

Their daughter, Elizabeth Ober, went on to become the common-law wife of part-Aboriginal man, Fred Davis, who was Prof. Davis’s grandfather (see Figure 2).

Mrs Ober lived to the grand old age of 95, some 20 years more than the average Aboriginal woman today. (see Figures 5 & 6)

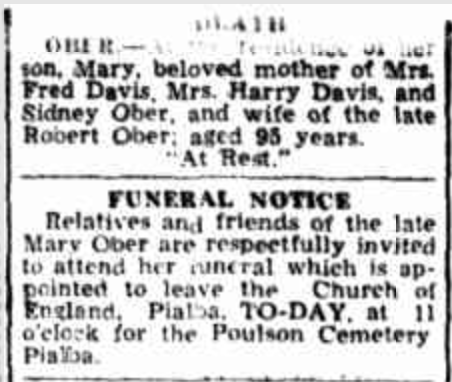

Figure 5 - Death notice for Prof. Megan Davis’s SSI great-grandmother Mary Ober (Wallangartie). Source: Maryborough Chronicle, 27 May 1948, p. 4

Figure 6 - Death record for Mary Ober.Source: Qld BDM records

Wallangartie (Mrs Ober) did not go back to live permanently in Vanuatu after her initial labour contract expired, but instead she returned to settle in Queensland, married, had children and integrated into society. She received a basic ‘indigent allowance’ and ultimately she was deemed entitled to, and did receive, the government old-age pension [possibly as a result of the widows pension and social service reforms of 1942-1946] until she died in 1948 at the ripe old age of 95.

Her 1948 newspaper obituary gives the details of her life:

LINK WITH EARLY DAY ISLAND LIFE

In the death of Mrs. Mary Ober, Urangan, on May 25, there was severed another link with the old black-birding days, when natives from the South Sea Islands were brought to Queensland to work for the sugar industry (writes our Torquay correspondent).

The late Mrs. Ober, who was in her 95th year, was born on Marlo Island, in the New Hebrides, and was brought to Queensland as a young girl in her teens.

She often spoke of her first position, in which she worked for white people on Magnetic Island [off Townsville]. She could not understand one word of English, but her mistress was very kind and very patient, and would repeat everything several times, until Mary could say it after her.

She always spoke very highly of those people, for whom she worked three years. [Ed. note: this indicates a typical, legal, indentured labour 3 year contract, willingly entered into].

They took a great interest in the island folk, and at Christmas time would try to give them a little reminder of their island home by killing a pig for them. The flesh of the pig and fish was the staple diet of the islanders. If there were many islanders on Magnetic at Christmas time, they would kill several pigs for them.

Mrs. Ober, when telling the story, would say that they did it out of the kindness of their hearts, but it would tend to make many of them homesick for their native isles.

After leaving Magnetic island, Mrs. Ober worked in Townsville, Cairns and Cooktown.

After her years of probation were completed she was free to return to her island home, but by that time she had become accustomed to the ways of the white people and had overcome her home sickness, but she had not heard from her home folk all those years, and so she decided to return home.

There was always much feasting and jubilation when one of the long lost ones returned. Mrs. Ober said that she remained on the islands for twelve months or so, and then returned once more to Queensland on her own free will.

On her return to Queensland, Mrs. Ober worked in the Maryborough district, on the Yerra Sugar Plantation.

There she did all of the work from cutting, thrashing and planting cane, and working in the mills, to scrub cutting and clearing.

It was at Yerra where she met her late husband. It was there they were married and raised their children.

Later they came to work for Mr. Scotney, Doojong, Urangan-road. In her younger days Mrs. Ober was a great walker and it was a very common sight early on Sunday mornings, to see her and her son Syd, wending their way into Pialba, to the seven o'clock church service conducted at the Church of England a distance of 5 miles or so. On winter mornings they would leave before sunrise to get to church in time for the service and then they would walk home again afterwards.

On Marlo Island, Mrs Ober would say the people were kind and always helped others and this tradition was carried on by the Islanders in Queensland and always made their home a home for others who came after.

Mrs. Ober never forgot her native tongue, and even to the last, would teach her grandchildren songs and ditties in the island language, and, strange to say, she never quite mastered the English tongue. After all her years of residence in Queensland she still spoke broken English.

After her husband's death 15 years ago she lived with her son, Syd Ober and his wife and family at Urangan. She was able to look after herself until the last. She was very fond of sewing, and loved patching which was a boon to the mother of her small grandchildren.

She did not possess very many clothes for the indigent allowance she received was not conducive to extravagance. After years of faithful service to the country of her adoption, she was granted the monthly sum of £1 1s.8p. per month, on which to cloth and feed herself. Her family tried often to get the old-age pension for her during those years, but it was not until three or four years ago that she was granted the full old-age pension.

The late Mrs. Ober is survived by two daughters and one son. Elizabeth (Mrs. Fred Davis), Annie (Mrs. Harry Davis), and Syd Ober, also 17 grandchildren and 17 great-grand children. Her husband pre-deceased her by 15 years. One son died in infancy, and another son died 20 years ago. One daughter, Mrs. Harry Davis, is well known for her social works for the Church of England and the Bush Children's Health Scheme.

The funeral took place from the Church of England Pialba, and was conducted by the Rev. Mr. Perkins.

- Obituary Maryborough Chronicle, 9 June 1948, p. 3 [our emphasis]

What this obituary tells us is that Prof. Davis’s great-grandmother, Wallangartie (Mrs Ober) expressed her own agency during her lifetime - she signed up initially to work for her very kind, white mistress on Magnetic Island for three years; she then worked elsewhere in Queensland before returning to her island home in Vanuatu. However, she only remained a year or so before once again signing-up to return [or just came back] to work on a Queensland plantation ‘on her own free will’.

We suspect that Wallangartie had no qualms about what her great-granddaughter Megan might think 170 years later of her decision to switch from a traditional life on a Vanuatu island (perhaps like the Aoban - from Ambae, Vanuatu - girls below) to a life of ‘modernity’ as an immigrant in Queensland.

Figure 7 - Indicative photographs of what Wallangartie might have looked like on leaving her island on her initial contract, compared to how she might have dressed and looked after becoming established in Queensland. Source : N/a

Wallangartie was not ‘enslaved’ in the sense most people understand that word with visions of the ‘chattel slavery’ of the Southern USA as depicted in the movie, Gone With Wind.

She was paid an amount of money that she and her compatriots must have considered acceptable otherwise the indentured labour trade would not have lasted the 40 or so years that it did. Indentured workers would not have re-signed two or three times as many did, or settled permanently in Queensland as cane workers, if they did not agree that it was worthwhile for them to do so.

She was not deported when the indentured labour programs ceased in the early 1900s, indicating that she had settled and integrated into Queensland society well enough that she was ‘exempted’ from deportation.

2 The Actual Lived Experience of Tinwilligan [Tanwilligan] (aka William (Billy) Willighan)

[see Note 1 below on how genealogists determined that this is Prof. Davis’s great-grandfather]

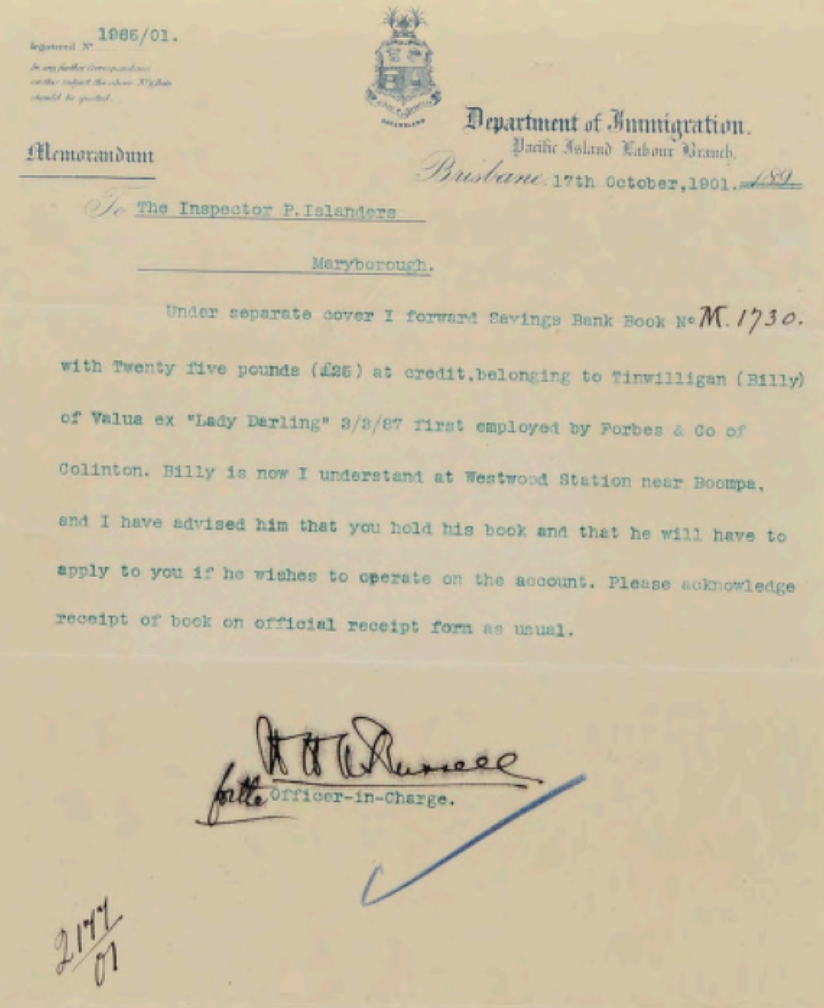

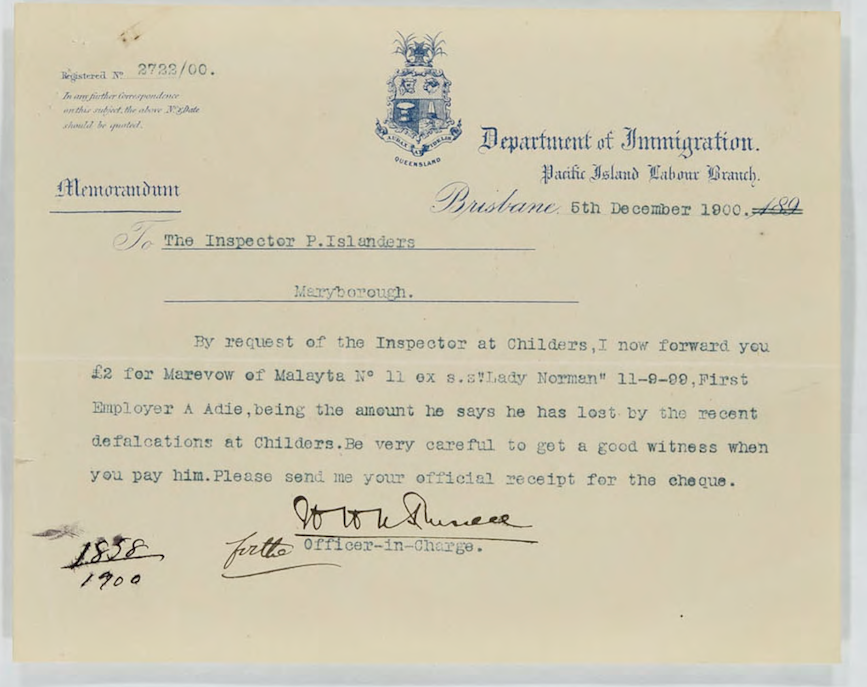

A 1901 memorandum (see Figure 8) from the archives of the Queensland Dept. of Immigration has been located describing the savings of a Billy Tinwilligan, who we claim was Prof Megan Davis’s great-grandfather.

The text of the memo reads:

17 October 1901

From: Department of Immigration, Brisbane

To: The Inspector P. Islanders, Maryborough

Under separate cover I forward Savings Bank Book No. M. 1730 with Twenty five pounds (£25) at credit, belonging to Tinwilligan (Billy) of Valua ex “Lady Darling” 3/3/87 first employed by Forbes & Co of Colinton [Qld]. Billy is now I understand at Westwood Station near Boompa [Qld], and I have advised him that you hold his book and that he will have to apply to you if he wishes to operate on the account. Please acknowledge receipt of book on official receipt form as usual.

Figure 8 - Memo on the savings bank account of Prof. Megan Davis’s great-grandfather Tinwilligan (Billy).Source: Qld SSI Archives

A few other records were also located, such as a wages register, some cash deposit records and his Death Certificate listing one of his sons as being Fred (Prof. Davis’s grandfather).

From the Death Certificate (above) we see that Prof. Davis’s great-grandfather lived to the age of 80.

In 1936, when he died, the Australian general population life expectancy (at birth) was about 65 years for ‘white’ Australians. In 1856, when he was born, the life expectancy for a ‘white’ Australian (at birth) was less than 35 (see Figure 9).

Thus, this family member of Prof. Davis’s had well and truly, ‘Closed the Gap’ by living some 15 - 45 years longer than ‘white’ Australians! Not bad for someone who we are told was an overworked slave.

Figure 9 - Historical Life Expectancy for Australia. (Source)

The records show that Tinwilligan (Billy) arrived from Valua [Vanuatu island of Vulai? or Ile Valua?] on the “Lady Darling” on 3/3/87. We could not establish any further details of this exact voyage, but we did find a reference to a schooner called the Lady Darling that was associated with the South Sea Islander recruitment trade.

Figure 10 - Newspaper report of the “Lady Darling” (schooner) being shipwrecked in the New Hebrides (Vanuatu) off Malicolo on 7 March 1881 [six years prior to Billy’s arrival].This suggests that the Lady Darling was recovered, repaired and out back into service - or perhaps a new ship of that name appeared in the trade? (Source:The Brisbane Courier, 28 March 1881, p. 2)

Was Tinwilligan (Billy) kidnapped or did he sign-up under a indentured labourer’s contract and come of his own free will to Queensland?

Professor Davis asserts that her ancestors were kidnapped and enslaved. We haven’t been able to locate a contract specifically related to Tingwiligan, but the fact that he arrived in 1887, some twenty years after the labour trade had begun, suggests that he would have come willingly and legally under contract.

His pay and savings details were officially recorded (see links to records above), so this suggests the authorities had him on their books and he most likely was therefore a signed-up, indentured labourer under a contract, such as shown in Figures 11A&B (this particular form from 1892 only has the details recorded on the back page about this labourer, who is reported to have died).

Tingwilligan had arrived only 5 years earlier (1887) than this form record (1892), which is based on the 1884 Labour Act, so it is more than likely that he was under a similar written contract.

Figures 11A&B - Typical Indentured labour contract under 1884 Act - this example dated 1892(Source: Qld records)

The 1887 arrival date of Tinwilligan also means that he was most likely not kidnapped as the recruitment trade was well established by then (see Figure 12 for numbers of recruit arrivals per year).

Although outright kidnapping did certainly occur in the very early years of the trade (1860-70s), by 1887 the trade was well established and regulated and the islanders were wise enough not to seccumb to kidnappers (although some reports of kidnapping were still reported in the 1880s in the Solomons, with the last recorded one being 1894. Overall, it has been estimated that less than 5% of recruits were kidnapped, although 20-25% may have been indentured illegally in the sense that the paperwork, or mutual understanding, was incomplete (see Further Reading “Definitions - Kidnapping” below).

Figure 12 - Statistics for the number of South Sea Islander indentured labourers (Kanakas) entering Queensland from the ”early days of black-birding” in 1863 to the cessation of the trade in 1904. Note that the total is the total number of contract entries and includes many individuals who contracted more than once. The estimate is that these 62,565 contract entries represent about 50,000 individual islanders, that is some 12,565 were repeat contracts. Source TBA

In fact, the islanders were well accustomed to the labour trade by 1887, as they had seen with their own eyes the successful return from Queensland of many of their emigrant fellow-villagers. These returnees were rich by island standards and loaded with valuable goods and gifts on their return (Figure 13).

Figure 13 - Photograph of ‘cashed-up’ Kanaka workers returning to their island from Queensland.(Source: TBA)

In fact, the recruiters found that, by the late 1870s, many islanders were so keen to join the trade that the need to carry out any illegal kidnapping became largely redundant in the islands.

Prof. Davis’s great-grandfather was more than likely an eager young man, who willing joined the trade and indentured himself on contract in Queensland. So popular was the pull of Queensland that newspaper reports indicated that often the recruiter’s boats were swamped with more recruits than they could handle!

Figure 14 - Newspaper clipping outlining eagerness of some South Sea Islanders to sign up as labour recruits for Queensland plantations.Source:Mackay Mercury, 26 January 1878, p2

3. The Actual Lived Experience of Booty (aka Robert Ober)

Booty (aka Robert Ober) was born in 1852 on Aoba (Ambae) Island, New Hebrides (central Vanuatu), South Sea Islands. He arrived in Queensland “in the early days” and died at age 81 on 24 November 1933 at Point Vernon, Queensland.

We know that he was one of Prof. Megan Davis’s great-grandfathers from the information in his death notice and obituary.

1933 Death Notice Maryborough Chronicle, 21 November 1933, p. 6

OBER.—At Urangan-road, Pialba, on November 20, Robert Ober, beloved husband of Mary Ober, and father of Sidney Ober, Elizabeth Davies [sic Davis] and Annie Davies [sic Davis]; aged 81 years. "At Rest."

1933 Obituary Maryborough Chronicle, 21 November 1933, p. 9

MR. ROBERT OBER

There passed away at Urangan-road, Pialba, yesterday, a well-known identity of the district, Mr. Robert Ober. He was born in the South Sea Islands and came to Mackay in the early days, where he worked on the sugar plantations. After three years in that district he returned to the Islands. Later he came back to Australia, settling at Yengarie where he followed work on the sugar plantations. He married a countrywoman, and subsequently went to Urangan-road, where he was employed by Mr. H. Scotney for 20 years. He is survived by his widow, one son (Sidney, Urangan-road), and two daughters (Mrs. Elizabeth Davies [sic Davis] and Mrs. Annie Davies [sic Davis], Point Urangan). The funeral will move from St. John's Church of England, Pialba, this afternoon for the Polsen cemetery.

Prof Megan Davis and her sister Lucy claimed in the ABC’s Australian Story documentary that their, ‘grandmother Elizabeth Ober was a South Sea Islander woman.’

From the above death notice and obituary we now know that Elizabeth Ober’s father was a South Sea Islander named Robert Ober, which is further confirmed by Elizabeth’s birth record below. This lists her father as “Booty (aka Robert Ober)” and her mother as Woolangarty (see Figure 16).

Elizabeth Ober’s married name was Davis [Davies] as she was the common-law wife to part-Aboriginal man, Fred Davis, Prof. Davis’s grandfather.

Thus we can now confirm this alleged branch of Prof. Davis’s family tree as shown in Figure 15.

Figure 15 - Excerpt of one of the branches of the alleged Family Tree of Professor Megan Davis showing her Aboriginal and South Sea Islander ancestry, with her grandmother Elizabeth Ober as being 100% Ni-Vanuatu, South Sea Islander.

As further confirmation that the above family tree branch is correct, we located Elizabeth Ober’s birth record which has Booty (aka Robert Ober) as being her father and her mother as Woolangarty (aka Mary). Her birth name is recorded as Elizabeth Woolangarty, her mother’s name, which suggest that her parents were not married when she was born.

Figure 16 - Extract of the Queensland birth record details for Elizabeth Ober showing her parent’s names. Elizabeth, and her siblings, are registered under both parents first names as their surnames. Neither Woolangarty nor Booty had a last name.

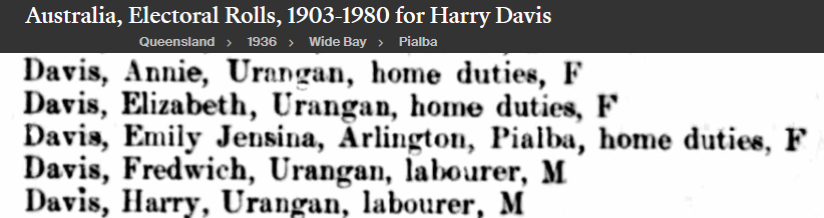

Some further information we obtained were the Queensland electoral rolls from as early as 1931, which clearly showed that Prof. Megan Davis’s Aboriginal ancestors had the vote contrary to much popular myth that Aboriginal people were disenfranchised until 1967 [See Note 2 below].

Also listed along with Fred Davis were his brother Harry and their two South Sea Islander wives Elizabeth (nee Ober) and Annie (nee Ober) who were also sisters, as well as sisters-in-law by their marriages to the two brothers, Fred and Harry.

Figure 17 - Extract of the Queensland Electoral roll of 1931 for Pialba showing the Aboriginal Davis family voters

Figure 18 - Extract of the Queensland Electoral roll of 1936 for Pialba showing the Aboriginal Davis family voters

Figure 19 - Extract of the Queensland Electoral roll of 1949 for Pialba showing the Aboriginal Davis family voters

Figure 20 - Extract of the Queensland Electoral roll of 1954 for Pialba showing the Aboriginal Davis family voters

Was Booty (aka Robert Ober) Kidnapped or did he come of his own free-will to Queensland?

Professor Megan Davis appears to prefer the negative “kidnapping” narrative to describe how her South Sea Islander ancestors came to Australia but, as we have shown with two of her ancestors above, we could find no evidence that they were kidnapped and brought against their will to Queensland.

Indeed one of her ancestors, Wallangartie [Woolangarty] (aka Mary Marlo, wife of Robert Ober (Booty) had at first returned to her island after her three-year indenture period was up, but in 12months she had decided to return to Queensland - hardly the action of a ‘kidnapped’ and ‘enslaved’ islander.

Her husband had a similar experience. After his initial 3-year contract of indenture expired he ‘returned to the Islands [and] later he came back to Australia, settling at Yengarie where he followed work on the sugar plantations. He married a countrywoman [Wallangartie], and subsequently went to Urangan-road, where he was employed by Mr. H. Scotney for 20 years.’

These life-choices hardly sound like the action of islanders who, as Prof. Davis told us in the ABC’s response,

‘… were brought here, often against their will, [where the] history indicates that over the past century their general treatment was as close to slavery as the laws of the time would allow. White society used them as labourers when needed and discarded them when no longer needed.’

From what we can surmise, it appears to us that Booty too was expressing his own agency - he went to Queensland for the adventure or financial opportunity, returned home to his island a relatively rich man. After 12 months he realised a better future for him lay in Queensland so he returned, settled down as a married man and had a daughter Elizabeth, who became Prof Davis’s grandmother, and the rest is history.

NOTES

Note 1 - Finding Tinwilligan

How did our genealogists determine that Tinwilligan [Tanwilligan] (aka William (Billy) Willighan) was Prof. Davis’s great-grandfather?

During this work, the genealogist researchers easily traced Prof. Megan Davis’s paternal line back to her grandfather, Fred Davis.

From Fred Davis’s death certificate they found that his father was recorded as “William Willigan Davis” [details on his Aboriginal mother, Lily Davis (nee Johnstone) will be reported on in a subsequent post].

Figure 24 - Extract of Fred Davis’s Death and Burial Details. Source: 1978 Burial Frederick “Fred” Davis - Find a Grave

We also know that Fred Davis’s father was a South Sea Islander (SSI) because, from a record in the 1962 Native Housing Register, Fred Davis is listed as a H/C [Half-caste Aboriginal man] with a SSI father. This record also confirms that Fred was part-Aboriginal. It thus confirms that he and his community considered he was part-Aboriginal and supports the claim by Prof. Megan Davis that she is of Aboriginal descent via her grandfather Fred Davis.

Figure 21 A.Source: 1962 Native Housing

Figure 21 B.Source: 1962 Native Housing

Thus, to find Fred Davis’s father, our researchers needed to search the records looking for a South Sea Islander man, named William Willigan Davis (or a closely similar name given that traditional SSI names were often routinely varied and/or Anglesized), in the correct age bracket to be the father of Fred (who was born ca1890/3 and died in 1978) and in the correct geographical area so as to be linkable to Fred.

After much computer and AI searching, the only candidate that appeared from the records was a SSI man known as Tinwilligan (Billy). The primary document supporting this candidate is the wages memo in Figure 8 above.

Our researchers are confident that this is Fred Davis’s father given that:

Tinwilligan was his native name, from which an Angelized name of William logically follows (from Tin..willi..gan), and shortened to ‘Billy’ in the typical Australian vernacular;

Tinwilligan arrived in Queensland via the Lady Darling voyage of 3/3/1887 and started work at Colinton [Qld] (as per memo in Figure 8). Fred Davis was born in Warra, Qld, which is only 180km west of Colinton (see Map 1 below), around three to six years later in 1890 to 1893 [various birth years for Fred are recorded]. This fits with a logical scenario where Tinwilligan moved after his first 3 year contract had finished allowing him to meet Fred’s mother in/near Warra;

By 1901 (as per the memo in Figure 8) Tinwilligan was working at ‘Westwood Station near Boompa’, which is only 18km east of the town of Biggenden (see Map 2 below) where the man known as Billy Willighan died in the local hospital in 1936 at the age of 80. One of his two sons on the death certificate is recorded as being named Fred (see Figure 22).

Tinwilligan’s birth year is thus 1856, (1936 less 80) making him about 31 years old when he arrived on the Lady Darling, which is an acceptable fit.

Fred lived a large part of his life only 120km east of Biggenden in Urangan, where he also died (See Map 2).

Our researchers only ever found one Fred Davis in the Urangan, Pialba and Hervey Bay area.

Thus the names, times and geography all fit well to support the notion that Tinwilligan was one and the same man as Billy Willigan and William Willigan Davis, who had a son named Fred and lived and died in the same districts as Fred Davis, who we know was Professor Megan Davis’s grandfather.

Figure 22 - Extract of Death Certificate for Billy Willighan (aka Tinwilligan (Billy), aka William Willigan Davis), Professor Megan Davis’s great-grandfather.

Map 1 - Warra town (circled on left) is where Fred Davis was born; Colinton (circled on right) is where Tinwilligan first served his indentured labour contract.

Map 2 - Biggenden (circled on left) is where William Willigan Davis died in 1936. Boompa (circled in centre) is where Tinwilligan (Billy) first worked. Urangan (circled in right) is where Fred Davis lived and died.

Note 3 - Name variations for Wallangartie

Invariably in the old days, various spellings were recorded for people’s names. This is especially the case for South Sea Islander records given their initial lack of English, difficulty by the authorities in understanding or knowing naming protocols for Islanders, plus the general Australian habit of Anglesizing the names of New Australians and/or giving them shortened or nick-names.

Thus, Prof. Davis’s great-grandmother Wallangartie [the name we use here] has been various recorded as Mary Marlo, Mrs Robert Ober, Woolangarty, Waluenartis and even Maluncarlis on various of her children’s birth certificates (See Figures 1 & 23).

Figure 23 - Extracts of Birth Certificates for some of Wallangartie’s children.

Figure 24 - Source p75

The Need For Historical Context

Many activists today want to portray the labour markets in colonial Queensland and NSW as some sort of racist, plantation system built on the back of black slave labour. These activists reproduce photographs showing forlorn looking workers in cane-fields to support their case.

Life and work was tough in those days, but that was the way things were for all working people back then - blacks, whites, Chinese, Japanese and Islanders. Most of the activists complaining today always seem to look as if they have never done a hard day of manual work in their lives.

The historical reality is that Australia has always, and continues to be, a growing economy in need of labour. In pre-colonial times the majority of the daily grind was provided by the labour of Aboriginal women.

After 1788, the labour was predominately supplied white convicts.

Figure 25 - Convict Tramway, Van Diemen’s Land (Wikipedia)

From say, the 1850s onwards, it was predominately ‘free-immigrant labour’ - white shepherds, settlers, miners and in more remote regions Aborigines, as well as their horses. By the 1880s they were joined by white factory workers and a trickle of Kanaka labour recruits from the South Sea Islands.

To put the relative populations into context, the population of colonial Australia in 1900 was some 3.74million (Figure 26), after which some 162,000 convicts had arrived and some 62,000 individual Kanaka contracts issued (to approximately 50,000 individuals as many signed up two or three times). Thus, the influence of 50,000 South Sea Islanders was hardly influential in the bigger demographic picture.

Figure 26 - The historical convict population (ca163,000) and the South sea Islander population (ca50,000) are insignificant on a national basis to the total colonial population on the eve of Federation in 1900 (ca3.74million). Source

Was the Indentured Labour Trade Based on Kidnapping and Slavery?

If, as the Davis family believe , the South Sea Islander labour trade was so bad, and based on kidnapping and slavery, why did it last some forty years and why did the Davis family ancestors sign-up and return on second-contracts? And more importantly, why did they seek exemption certificates that entitled them to stay in Australia permanently?

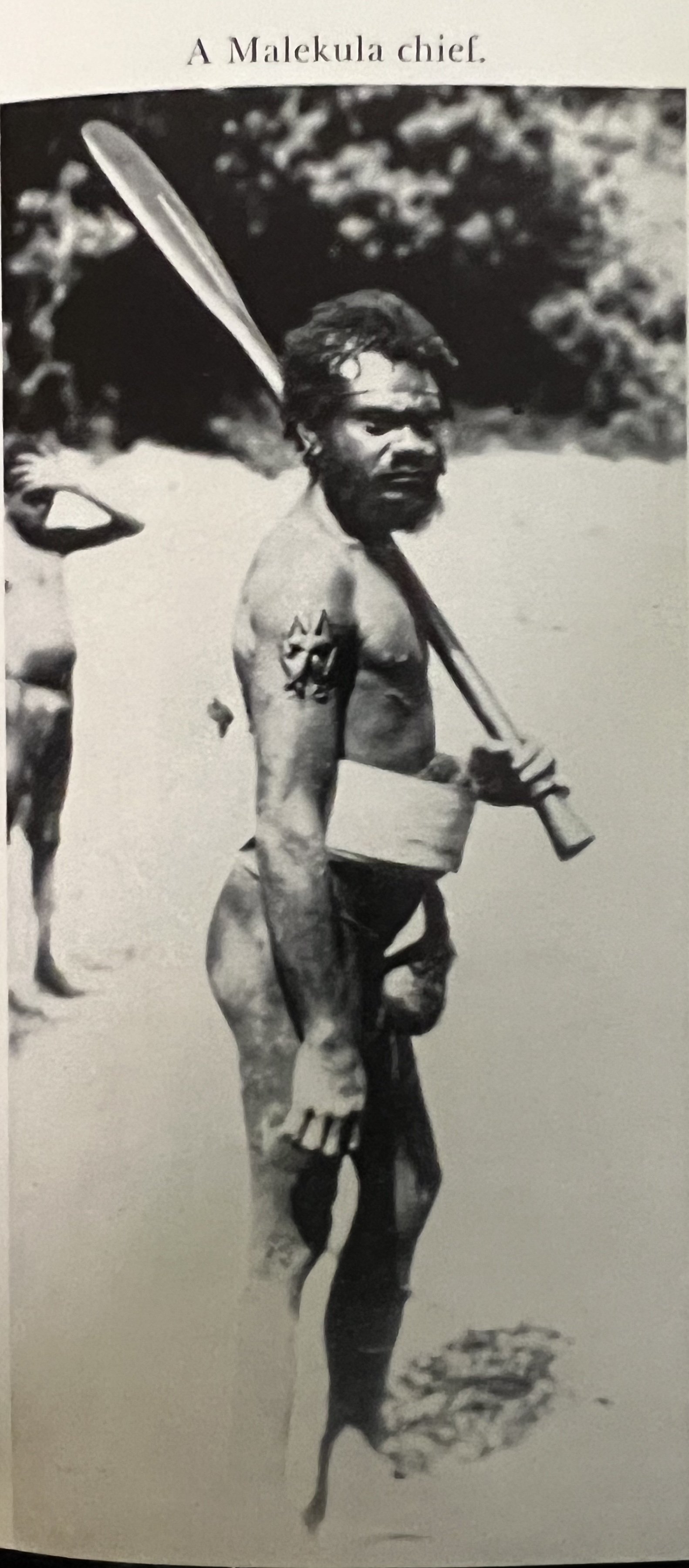

Some of reasons are related to the fact that life in the islands was not always idyllic.

There was constant warfare in many islands, not only between tribes but also within tribes. Many of the senior men were ruthless fighters, which is easy to image when looking at some of Prof. Megan Davis’s possible ancestors (Figures 27 & 28).

Figure 27 - Malekula (Vanuatu) warrior. Prof Davis may have had an ancestor such as this.Source: E. Docker The Blackbirders, 1970, p52op

Figure 28 - Malekula (Vanuatu) warrior. Prof Davis would have had an ancestor such as this.Source: E. Docker The Blackbirders, 1970, p52op

Furthermore, in some South Sea Islands such as the Solomons, head-hunting was rife, as written about by Peter Corris (see Figures 29A&B).

Figures 29A & B - Extract from Peter Corris’s, Passage, Port and Plantation, p29-30. [Note: western islands of the Solomons]

Corris concludes that indigenous slave raiding and head-hunting reduced the number of labour recruits seeking to escape Solomon Island society by providing enough ‘enjoyment’ for the men to keep them at home.

Many of us would wonder however, why 17,756 Solomon Islanders still decided instead to indenture [‘enslave’] themselves to Queensland sugar plantations? This group represented 28% of the total of recruits to Queensland - the second highest share after Vanuatu (53% - Figure 12).

Was it because that a life consisting of two choices - hunting-heads or having your own head hunted - was not that attractive compared to the access to modernity that a labour contract in Queensland offered?

Modern Day Indentured Labour from the South Sea Islands

When the activists take to the high-moral ground and blame a ‘racist’ colonial Australia for the South Sea Island labour trade, it is instructional to point out that the trade still exists.

However, over the past 150 years a modern, honest and moral country such as Australia keeps progressing, at the best of our ability, to regulate the trade to enforce rights and obligations on all participants.

See Figures 39 & 40 for a modern day example of the South Sea Islander indentured labour trade going well.

Figure 30 -Source:The Australian 18 August 2023

Figure 31 -Source:The Australian 18 August 2023

And an example where the ABC’s 4Corners program are telling us that there are problems with the modern day trade.

Figure 32 - In 2015 the ABC was telling us that there is widespread “Labour exploitation, slave-like conditions found on farms supplying biggest supermarkets” built around 417 Visa workers (modern form of indentured labour), but then they would say that wouldn’t they?Source: Labour exploitation, slave-like conditions found on farms supplying biggest supermarkets

[Ed. Note : The same ABC that: ABC admits it may have underpaid 2,500 casual staff for six years].

Further Further Reading

Below is a good account of the how, why and what happened to, a couple of young Solomon Island '“boys” Tobebe and Afio, who were kidnapped for the Queensland labour trade. The activist Left will play up the first part of their story, but will never mention the final outcome.

Readers can make up their own morality play on what happened to them, but at the end of the day it’s history and the boys dealt with life as best as they could, on their own terms. We today should not feel guilty at all, only interested and willing to learn.

Figure 33A,B & C - Source: Corris p26

Source: Corris p27

Source: Corris p29

An Interesting items come across during our research

Figure 34

Letters/ memos from the Queensland Archives showing that the authorities seemed to be doing their best, with limited resources, to ensure the Kanakas were treated fairly

Figure 35 series

What Is Defalcation?

The term defalcation primarily refers to an act committed by professionals who are in charge of handling money or other resources. This typically entails the theft, misuse, or misappropriation of money or funds held by an official trustee, or other senior-level fiduciary. As such, it's considered a form of embezzlement, either through the misallocation of funds, or the failure to account for received funds.

The following is a document that shows that the turn of century (1902), our society’s attitude was changing with regard to labour in the tropics and the rights of workers. Up until then it was generally considered that white labourers could not do manual labour in the tropics and labouring wages were to be kept as low as possible. However, the working man started to agitate for better pay and conditions and wanted to ensure wages were held high. To achieve this organised labour had to push back against commercial interests and one of the first ‘casualties’ was low-wage, indentured labour. Hence, the termination of the SSI labour-trade and the eventual expulsion of most of the South Sea Islanders.

Figure 36 - Letter from a grower D. Pratt illustrating the social change underway to move to white labour even when new SSI recruits were still available.

Mackay, 27th Feb 1902

H Hornbrood(?) Esq. (?), (?)

“I have indented 2 recruits per “Clansman” but I have now decided to try to grow cane with white labour.

Will you kindly oblige me by endeavouring to have the boys transferred to somebody who would like to have them.

Yours faithfully, D Pratt

The removal of new SSI recruits paved the way for the employment of ‘white’ cane cutters on higher wages and ultimately the emergence of the cost cutting mechanization of the sugar industry. Today Australia is one of the most efficient sugar producers in the world, a perfect example of progressive social policies leading to successful economic outcomes, even if that required the enactment of the White Australia Policy for some 60 years to effect this transition.

The short video below illustrates that the life of the Kanaka cane cutter and the early white cane cutters might not have been all that different.

Figure 37 - This ca1890 photograph is the favourite used by the activist Left to elicit sympathy for the ‘Kanaka cane-worker as oppressed slave’ narrative, despite their being well dressed and in Queensland voluntarily under contract.Source: Kanakas photographed on a sugarcane plantation with the overseer at the back of the group. ca. 1890. Cairns, Queensland, Australia. Collection reference: APO-25 Photograph Album of Cairns Views.

Figure 38 - These types of photographs from 1915 are not at all well known, even though they show cane-workers only some 25 years after those in Figure 46 adjacent. Is it because these cane workers are white?Source: The Robley family - “Between 1912 and 1915 , with his brother, Percy Charles, Sydney James worked as a cane cutter in Queensland”

Postscript: The history of the South Sea Islander Labour Trade is a lot more complicated and nuanced than we can hope to cover here in this post, which was mainly concerned with Professor Megan Davis’s family SSI ancestry.

At a future time we may return to the general topic of the Kanaks in Australia and post some more articles.