Merkel's Magic Wand - Turning Whites into Blacks

The greatest dangers to Indigenous Australians lurk in insidious encroachment by men of zeal, well-meaning, but without understanding.

- Ron Merkel QC in 2012

This is the third and final Post in our series, Revisiting Eatock v Bolt.

Part 1 and Part 2 should be read first, prior to returning to this post. Like the previous two, Part 3 also contains a lot of detail and evidence that I have tried to lay out in a logical, flowing sequence to support my argument and help readers come to their own conclusions.

Figure 1 - Pat Eatock - The Applicant in Eatock v Bolt 2011

This story begins in the early afternoon of Monday 28 March 2011.

Mr Ron Merkel QC has risen from his seat and, standing before Justice Mordecai "Mordy" Bromberg, he asks,

MR MERKEL: And your Honour, can I now read the witness statement of Pat Eatock, which is Exhibit A8, at tab 16? [Ref 4, p51ff].

HIS HONOUR: Yes.

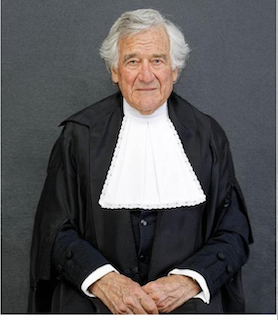

Figure 2 - Ron Merkel QC - Acting for The Applicant Pat Eatock [and the other eight witnesses]

MR MERKEL: Pat’s witness statement, she says:

“I am an Aboriginal person with Aboriginal ancestry. My grandmother, Lucy Eatock, was born in Carnarvon Gorge in central Queensland in 1874. … . I have photos of Lucy; she is clearly Aboriginal but not particularly dark. My grandmother’s husband, my grandfather, was an Aboriginal man, Bill [William] Eatock.

They married in 1894 [sic 1895]. He looked very Aboriginal. I have seen a photograph of Bill; he had a very black face and a long white beard. Bill was from the Woga Woga Waka Waka people from the Queensland coast from Fraser Island to Moreton Bay. Lucy and Bill had nine children, two girls and seven boys, including my father….

My father, Roderick Eatock, was the second youngest of Lucy’s nine children. He was born on the banks of the Darling River in 1909. I have lots of photos of my dad, and photos of some of his brothers. He was dark, much darker than his mum, Lucy.

My mother was Elizabeth Stephenson Anderson. She was born in 1909 in Scotland and came to Australia in about 1928.

I have spent a significant amount of time during my life putting my family history together. My sister, Joan, has also done a lot of research and written a manuscript about our family history which I have read…”

- Ron Merkel QC, excerpts from the recitation of his client’s witness statement (Ref 2, p51-2)

After taking twenty minutes to deliver Pat Eatock’s signed witness statement to Justice Bromberg and the assembled court, Mr Merkel then turned to Pat and said, “And, Pat, would you like to go into the witness box.”

Once there, she took her affirmation [Ref 3] by declaring to the court:

“I solemnly and sincerely declare and affirm that the evidence I shall give will be the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth.”

Justice Bromberg then directed the case to proceed [Ref. 2, p60]:

HIS HONOUR: Thank you, Ms Eatock. Would you like to take a seat.

MR MERKEL: I think I have been referring to you as “Pat”. “Mrs Eatock” or “Pat Eatock”, which – how would you like - - -?

PAT: Pat is fine.

MR MERKEL: Pat – okay. Pat, you have heard me read your witness statement?

PAT: Yes.

MR MERKEL: That’s true and correct?

PAT: That is true and correct.

MR MERKEL: Yes. Thank you.

Ron Merkel QC then sat down, his preliminary job done.

During the reading of Pat’s witness statement, Merkel had skilfully guided Justice Bromberg on a genealogical journey through his client’s Aboriginal ancestry - all the way from her ‘black face’ Aboriginal grandfather and her ‘clearly Aboriginal but not particularly dark’ grandmother - both of whom had lived together in a tent in the Queensland outback in the 1890s - down through the years and other family members of the last century to the courtroom today, where their granddaughter, Merkel’s ‘fair-skinned Aboriginal’ client, sat feeling, ‘offended, insulted, humiliated or intimidated’ by Andrew Bolt’s conduct, or so she told the court.

The notorious Eatock v Bolt case ran for another seven days in court and, after several months of deliberations, Justice Bromberg finally handed down his long, 470 paragraph judgement on 28 September 2011 [Ref 1]. This was more than two years after Andrew Bolt’s original transgressions were alleged to have occurred.

Figure 3 - The Hon. Justice Mordecai (Mordy) Bromberg. Source

It was a closely watched, and much analysed, monumental judgement that fed, and would continue to feed for a few more years still, a frenzy of political and law-school commentary and media attention.

Depending on one’s underlying political philosophy, Bolt’s loss was either a celebrated win for the so-called Progressive-side of politics, or an unmitigated disaster that would have long-term, adverse effects on Australia.

Either way, Eatock v Bolt represented a ‘watershed’ moment - a turning point for both free-speech and race relations in this country.

As Justice Bromberg read out his judgement, some paragraphs more than others caught my attention, for example, the so-called, Admitted Facts:

at 65 “By their pleadings, both Mr Bolt and HWT have admitted that each of Ms Heiss, Ms Cole, Mr Clark, Dr Wayne Atkinson, Mr Graham Atkinson, Professor Behrendt, Ms Enoch, Mr McMillan and Ms Eatock are of Aboriginal descent; that since each was a child, at the times of publication of each of the [Bolt] Articles, and at present, each person did and does genuinely self-identify as an Aboriginal person and did and does have communal recognition as an Aboriginal person. It is admitted that each of these persons has fairer rather than darker skin colour …”

and

at 154 “Ms Eatock’s mother was born in Scotland and came to Australia in about 1928. Ms Eatock’s Aboriginal heritage comes from her father. Her paternal grandfather was Aboriginal and her paternal grandmother had an Aboriginal mother and a non-Aboriginal father.”.

and

at 164 “Ms Eatock was cross-examined, but the evidence I have referred to was largely uncontested. I have no reason to not accept Ms Eatock’s evidence as truthful. I find that Ms Eatock does genuinely self-identify as Aboriginal. She has Aboriginal ancestry and communal recognition as an Aboriginal person. She did not choose to be Aboriginal. Her identity is a product of her upbringing. In her adult life she chose to be proactive about her Aboriginal identity. She is an Aboriginal person and is entitled to regard herself as an Aboriginal person in accordance with the conventional understanding of that racial description … I accept that she feels offended, humiliated and insulted by the [Bolt] Articles or parts thereof in the manner outlined by her evidence.”

- Extracts from Eatock v Bolt 2011, Ref 1

All the learned, legal practitioners in the court room on that day, from Justice Bromberg himself, to Ron Merkel QC and Mr Borenstein SC for the applicant, to Mr Young QC for the respondents, plus all the other legal attendants on their respective teams, they all seem to have concurred that Pat Eatock ‘has Aboriginal ancestry.' Not one raised in court any real concerns about the veracity of Pat Eatock’s claims of Aboriginal descent. No one asked to see her evidence or proof.

Consequently, all the ‘learned friends’ presumably agreed with Justice Bromberg when he began reading his long judgement, opening as he did with:

Reasons for Judgement

at 1. Ms Eatock has brought this proceeding on her own behalf and on behalf of people like her who have fairer, rather than darker, skin and who by a combination of descent, self-identification and communal recognition are, and are recognised as, Aboriginal persons.

Bromberg J believed that Pat Eatock had standing or locus standi to bring the case in the first place. He was satisfied that she had demonstrated possession of the necessary ancestry and descent to meet his definition as one of his, “Aboriginal persons.”

But, hypothetically, let’s imagine that Pat Eatock did not have Aboriginal ancestry. What would that mean?

It would mean that she would not have been an ‘Aboriginal person’ as defined by Bromberg J, and agreed to by the parties. She would thus not have been able to bring a case against Bolt under the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 - she would have had no standing to bring the case in the first place.

Justice Bromberg wrote his judgement based on evidence from Pat Eatock, who had said that her ancestry claims were, “the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth.”

But what if Pat’s story wasn’t the whole truth?

Had a great injustice been done, facilitated by Justice Bromberg, when Andrew Bolt and his publisher were convicted of breaching the Racial Discrimination Act?

In Part 2 of this series, convincing evidence was presented to confirm that ‘the truth’ regarding the ancestry of Pat Eatock’s grandmother was not presented during the trial.

Based on publicly available genealogical records, her grandmother, Lucy Harriet Eatock, was in fact found not to be of Aboriginal descent - both her parents had been born in Scotland. She did not, as erroneously concluded by Justice Bromberg have,“an Aboriginal mother.” [at 154]

Justice Bromberg had erred in fact.

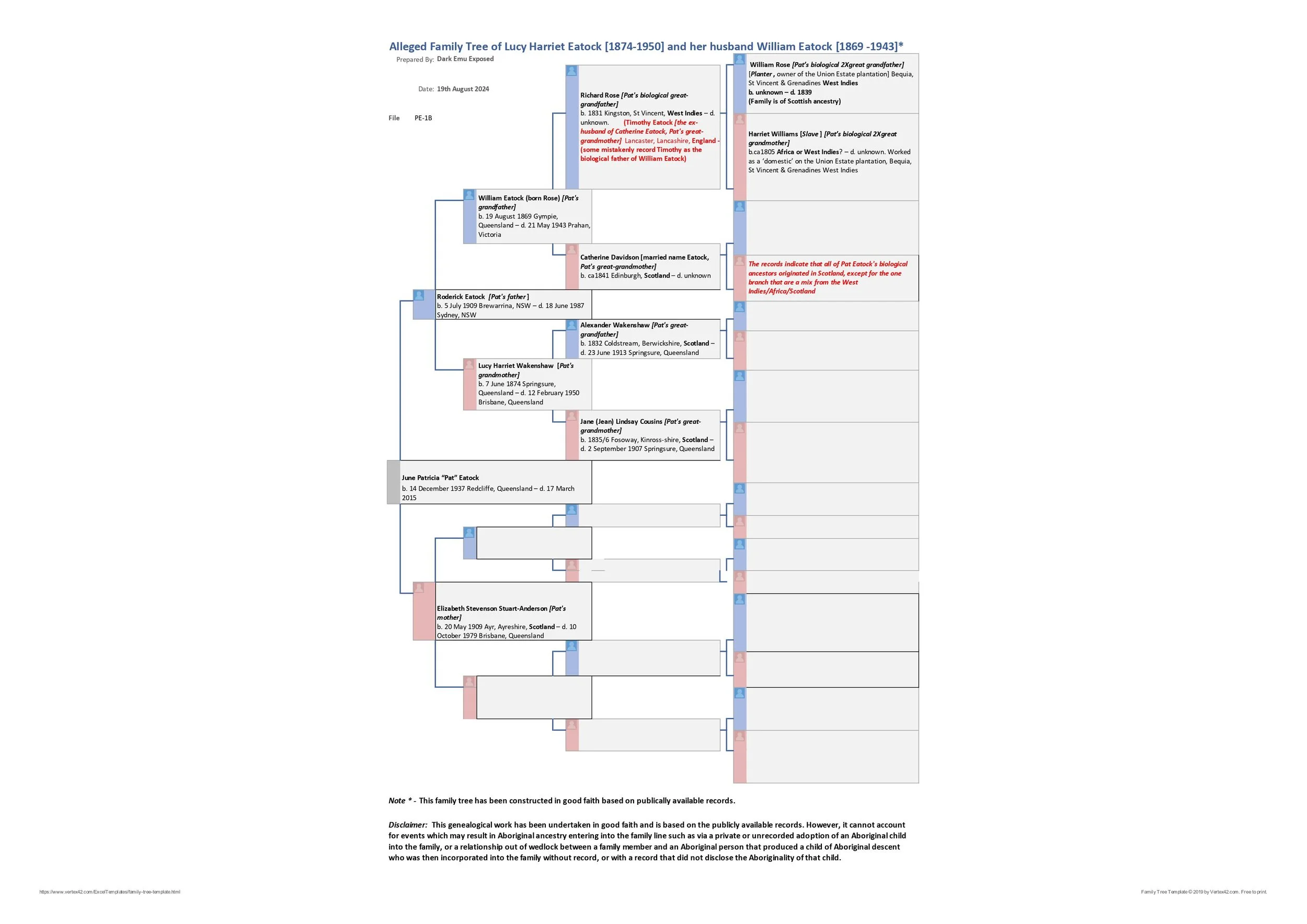

In this final Part 3 of the series, it will be shown that William Eatock [1869-1943], husband to Lucy Harriet Eatock [1874-1950] and grandfather to Pat Eatock was not of Aboriginal descent.

Pat Eatock was thus mistaken to have claimed that she was of Aboriginal descent via her paternal grandfather William and, more worryingly, Justice Bromberg had erroneously concluded that, “her paternal grandfather was Aboriginal” [at 154].

Justice Bromberg had once again erred in fact.

In reality, Pat Eatock had no Aboriginalty at all, and thus no standing in the action - the Eatock v Bolt case should have been dismissed for the farce that it clearly was on Day 1.

But it wasn’t and, as they say, the rest is history.

Until now.

1. Looking For William Eatock [1869-1943]

By the time Eatock v Bolt got to trial in 2011, there were already a number of published references regarding the ancestry of William Eatock, Pat Eatock’s paternal grandfather.

Firstly, in 1999 ABC Radio had broadcast a podcast program, Lucy’s Legacy, which is believed to have mentioned William’s life in passing while focusing on the program’s main subject, his wife Lucy Harriet Eatock [as detailed in Part 2; nb. the podcast is no longer publicly available].

The podcast’s producer, Lea Redfern had interviewed historian Hall Greenland as part of her research. The rough transcription notes of these interviews can today be found in the AIATSIS archives in Canberra, as part of the Joan E Eatock collection (AIATSIS MS 4304 [see here the excerpts of Redfern’s notes reproduced below].

Hall Greenland himself went on to write the Australian Dictionary of Biography’s (ADB) entry on Lucy Harriet Eatock in 2005.

Interviewer [Lea Redfern]: You’ve talked to a lot of contempts, families [incl. the Eatocks] attitudes to their Abl [Aboriginality]?

Greenland: Wasn’t talked about … only post Lucy’s death in 1950s … that people started to talk … some of the Eatocks decided to claim … others decided they were now part of white society and they’ve never mentioned it again and may or may not become annoyed if people did raise it. But all of my research points to the very obvious fact that their [sic there] was Aboriginality. That Bill [William] Eatock was probably orphaned during the Frontier Wars in Queensland, that he was adopted by a [sic] Scottish parents. He had a white older brother and a white younger brother both of whom have birth certificates that have been traced and Bill’s [certificate] wasn’t …[see point 1 below]

Interviewer: Why do you think that Lucy and her children didn’t talk about their Aboriginality?

Greenland: Wow that is a good question. I think they didn’t talk about it because, for two reasons, one they didn’t know … there was racial prejudice so they didn’t want to invoke that … shame … the lessor race … second reason … good reason … everybody supposed to have overcome … second half of century people started facing up and talking about it, but [back] then … people didn’t talk about it. [E]specially, if you lived in white society. They lived in an urban setting … they were workers … regardless of racial and cultural origins … in that generation people wanted to be Australians … melting pot people, melted …” [our emphasis]

Unlike the amateur story-teller that Joan Eatock turned out to be [see Part 2], Greenland at least has a degree in history, but the methodology he alludes to, in determining why he thought William was Aboriginal is, what many might think, a ‘novel’ approach to doing history [point 1 in his interview above].

Greenland correctly pointed out that William’s mother, Catherine Davidson, did have two other sons, both ‘white.’ The records show that these were, Donald Eatock born in 1866, three years before William’s birth in 1869, and James Eatock born in 1871, but who died within a month. Our researchers were unable to find any other children recorded as being born to Catherine beyond these three - the two ‘white’ sons and then William [Research notes on her marriages and two sons here]

Greenland was correct in 1999 that no birth record ca1869 in the name of a William Eatock had ever been found in the archives. This is still the case today. All the other commentators have therefore relied upon William Eatock’s own marriage record, and his mother’s marriage records, and the birth records of her two ‘white’ son’s [here], to show that the Englishman, Timothy Eatock, [b. ca1828 - d?] was allegedly William’s father. There is no dispute, except of course by his grandchildren - Pat and Joan Eatock - who needed William to have had an Aboriginal father to support their narrative and claims for Aboriginality.

Greenland however, takes another view, and a ‘novel’ approach at doing history.

He observed that Catherine Eatock had two ‘white’ sons with, who he believed was, Timothy Eatock, and both of the boys, Donald and James, had their births recorded. Catherine’s middle son, although known as William Eatock, had no birth record and Greenland seizes on this as an opportunity to further the so-called ‘Frontier War’ theory.

This theory was gaining much momentum by the late 1990s in which its adherents claimed that the Queensland pastoral frontier had been a place of brutal and constant “warfare” between the Aborigines and the settlers and pastoralists. The theorists claimed that it had led to widespread killings, and even massacres, of Aboriginal people such that numerous Aboriginal children emerged during this period as orphans, or were simply adopted or stolen to be enslaved as ‘house-gins’ or stock-boys. Even Pat Eatock in her court witness statement promoted the theory by falsely claiming that her great grandfather’s brother, Adam Wakenshaw had kept an Aboriginal woman as a “sex-slave.” [Ref 2, p51]

In line with this theory, Greenland, with no real evidence, unabashedly speculated that the reason why no one has located a birth record for William Eatock, the ‘black’ boy, is because he was,“probably orphaned during the Frontier Wars in Queensland [and] that he was adopted by a [sic] Scottish parents” [as cited above].

Greenland then went on to write the 2005 Australian Dictionary of Biography (ADB) entry for Lucy Harriet Eatock, where he recorded her husband William as being “an Aboriginal stockman”. Greenland cites no specific documentary evidence to support this claim, which suggests it was entirely based on his “Frontier War theory” as speculated above. The editorial staff at the ADB obviously approved this methodology when they peer-reviewed Greenland’s submission and then allowed it to be published.

Figure 5 - Excerpt from the Australian Dictionary of Biography entry for Lucy Harriet Eatock, Pat Eatock's grandmother. This premier repository of 'facts' on Australia's notable people from history thus promotes the error that William Eatock was Aboriginal. Source

This is not the way proper history is done. Historians who just join a series of dots in the historical record, hoping they are related and by making the observations fit their own pet-theory, are ultimately going to get found out, even if it is twenty-five years later, as we will now show is the case.

2. The Birth Record of William Eatock & Proper Methodology in Historiography

We have received a number of appreciative comments from readers of the Dark Emu Exposed website who are family history enthusiasts. They are fascinated by the methodology that accompanies many of the genealogical problems that are solved on our website.

The following piece of detective work and methodology is very instructional in this regard. It is an example of proper research historiography - thinking within the context of the times plus joining isolated historical observations with documentary, or other corroborating, proof and evidence, and not just relying on speculation or the parroting of the current orthodox narrative.

When our head genealogist got to the same contrary point in the Eatock family tree as everyone else had - on the one hand finding William at the top of his branch, but without a birth certificate; knowing that his father and mother were recorded as Timothy Eatock and Catherine Davidson [born in England and Scotland respectively], but then, on the other hand, finding that Australia’s leading historians and Federal Court jurists all believed that William was somehow Aboriginal - she thought something was not right.

Rather than just give up and fall into one of the two conflicting camps - William was either of English and Scottish heritage and non-Aboriginal, or he was an orphaned or stolen Aboriginal boy adopted into the Eatock family line somehow - she decided to make a cup of tea and think, and apply the historical method.

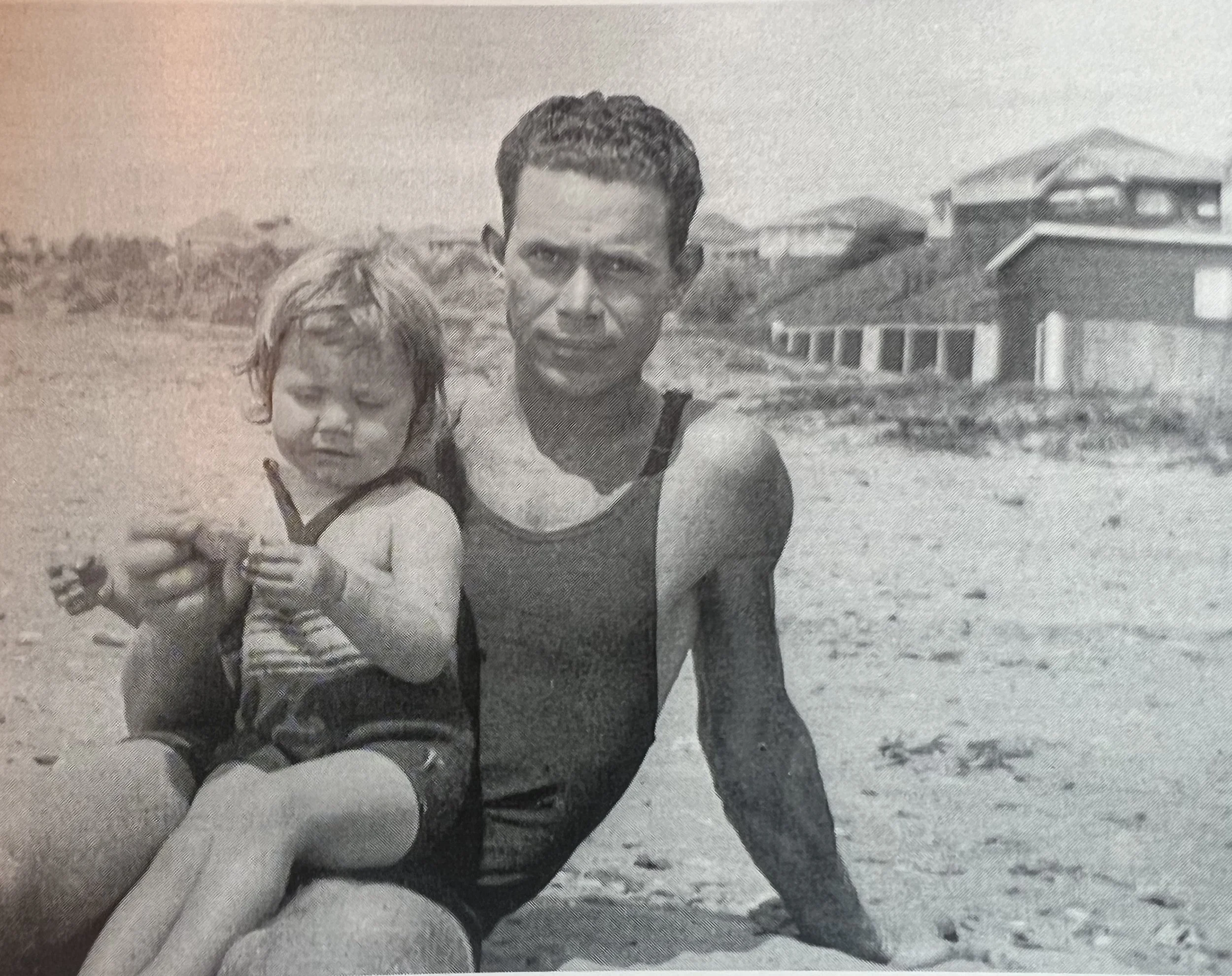

William probably wasn’t just of English and Scottish heritage she thought. No one had ever presented a photograph of him, but the family photographs below of his children, Roderick (Pat and Joan’s father) and brother Alex, clearly indicated that there were some non-European, perhaps even Aboriginal, facial features and darker-skin tones. The family knew themselves that there was some ‘colour’ in their ancestry, but it probably didn’t really matter much to their daily lives until Pat and Joan’s generation when, in the 1960s, ‘skin colour’ started to take on a much more political and profitable dimension.

Pat and Joan’s mistake was that they just assumed that their father’s obvious ‘colour’ was Aboriginal-based when, as we will show, it wasn’t.

Figure 6 - The 'blackness' of the Eatock family - Roderick Eatock (Pat and Joan's father) as a 13-year old boy laying down, front right, Grenfell NSW ca1922. [Note also the apparent 'blackness' of family members on the left] Source: Joan Eatock's book, Delusions of Grandeur, 2003

Figure -7 - Roderick Eatock (Pat and Joan's father) far right; with his wife and children and her Scottish parents. Brisbane Wharf 1940. Source: Joan Eatock's book, Delusions of Grandeur, 2003

Figure 8 - Roderick Eatock with his wife and kids, Brisbane 1950. Source: Joan Eatock's book, Delusions of Grandeur, 2003

Figure 9 - Roderick Eatock with daughter Jean at Redcliffe Queensland 1935. Source: Joan Eatock's book, Delusions of Grandeur, 2003

Figure 11 - Roderick Eatock with wife and Joan (undated). Source: Joan Eatock's book, Delusions of Grandeur, 2003

Figure 12 - Roderick Eatock with his son; outside Bardon home in Queensland 1951. Source: Joan Eatock's book, Delusions of Grandeur, 2003

Figure 10 - The 'blackness' of the Eatock family - Richard Alexander (Alex) Eatock (Pat and Joan's uncle & Roderick's brother) with wife Eileen; Bankstown NSW 1930. Source: Joan Eatock's book, Delusions of Grandeur, 2003

Figure 13 - Roderick Eatock surveying for the military 1942. Source: Joan Eatock's book, Delusions of Grandeur, 2003

3. So Where Did the Family ‘Blackness’ Come From?

Our genealogist first explored the ancestry of Timothy Eatock and Catherine Davidson back in the UK. Did either of them have a ‘coloured’ family member that then resulted in ‘blackness’ being brought into the Eatock family line when Timothy or Catherine emigrated to colonial Australia? After much research, no connections were found.

Then, the research re-focused on William’s mother, Catherine Davidson. The records indicated that she was not a ‘settled’ person. She had her first child, Donald, in 1866 out of wedlock, two years prior to marrying the boy’s supposed father, Timothy Eatock, in 1868. But then they appear to have separated and were living in different towns.

Life could be tough for a single mother in colonial times and Catherine appears to have taken up with another man, or men, having two more children in the process, William and James. She gave these boys the surname Eatock because that was still her legally married name. At the age of 31 she married for a second time in 1873 to a Thomas O’Neill. She probably became a bigamist with this second marriage, as no record has been found indicating that she divorced Timothy Eatock before marrying O’Neill [see #307 Marriage Record here]

There is some indication that Catherine might have still been using the Eatock surname in 1874, even after marrying O’Neill, as a ‘dead letter’ record to that name has been found. Her second ‘husband’ Thomas O’Neill died shortly later in 1879, and Catherine too seems to have disappeared from the records.

Catherine’s unsettled, perhaps even ‘loose’, character suggests that there was a real possibility that she might have had one or more relationships that produced a child out of wedlock. She might have used her maiden name to record that child’s birth. Alternatively she might even have taken another man’s surname ‘unofficially’. What this means is that the surname Eatock might not have been used to record her son William at his birth. This might explain why no birth certificate for a “William Eatock” has ever been found.

The genealogists therefore began to search under the subject’s maiden name, viz: “women named Catherine Davidson, who recorded a birth in Queensland, within say, a 2 to 5 year buffer either side of 1869 (William’s recorded date of birth from his marriage certificate - but he may have been wrong about his age).

This search resulted in quite a few “Catherine Davidsons” being located - the respective father’s names that were retrieved included a “Thomas Gould”, a “Charles Ernest Koppe”, a “James McIntosh”, amongst others.

Each search result had to be individually checked and then, as the checking progressed, the word bingo! was heard to reverberate through the Dark Emu Exposed offices - for there he was; a child named William in the 1869 birth records Book for the Wide Bay District [includes Gympie] in the Colony of Queensland kept by Registrar John Harry Stevens.

The book recorded that a Richard Rose had fathered a child named William, on 19th August 1869, in the town of Gympie in Queensland.

In the “Mothers” column was neatly written “Catherine formerly Davidson” Age: 27 years [i.e. born ca1842], Birthplace: Edinburgh, Scotland (Figure 14).

This was “our” Catherine Eatock, nee Davidson as her details matched both the records of her early years in Scotland and the recorded details for her marriages, and on her two other son’s birth records.

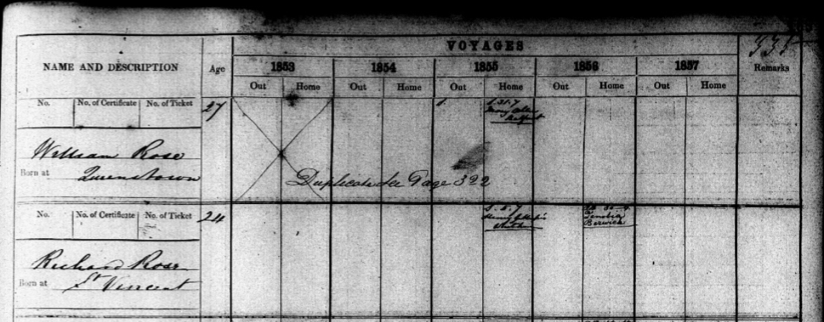

Figure 14 - Extract of the 1869 Birth Records Book for the Wide Bay District in the Colony of Queensland kept by Registrar John Harry Stevens. This is the record for the birth of William Rose [later known as Eatock] Source: Registered as 1869/C/1969 at QLDBDM. .Full page record here

The records continued to support the idea that Catherine led a very unsettled or even a ‘loose’ life:

- on her marriage certificate to Timothy Eatock she recorded herself as a “widow”, but there is no record of her ever having been married before;

- on her son William’s birth record (Figure 14) she has told the registrar that she and the boy’s father, Richard Rose, were married, on “7 August 1867 Sydney New South Wales” - this is not true; a search of the records revealed nothing; was she trying to make William’s birth look legitimate by making up a ‘fake-marriage’ in another colony that would have been harder for the registrar to check? [Ed. does this family have a gene for ‘expediency’ or even ‘lying’?]

- her marriage to Timothy on 24 August 1868, is exactly one year prior to her giving birth to William on 19 August 1869, who was conceived with another man, Richard Rose, just three months after her wedding day with Timothy. It is not surprising then that the records indicate that Timothy and Catherine were living apart shortly after getting married.

Also noticeable is that the “Informant” column on William’s birth record says, “Certified in writing by Catherine Rose mother Gympie”. Catherine was calling herself and her child Rose, even though she never married Richard Rose.

This is why no one has ever located a birth certificate for William Eatock - there isn’t one, because Eatock was his acquired or adopted name after his birth. His name at birth was Rose, that of his biological father, Richard Rose.

4. Has the Source of the Eatock ‘Blackness’ been Found?

Even more tantalising however, are the details recorded for William’s father: Richard Rose; Profession: Miner; Age: 38 years [i.e. born ca1831]; Birthplace: Kingstown, St Vincent, West Indies

Could this be the real source of the ‘blackness’ in the Eatock family line’ - the West Indies?

At the risk of being accused of ‘racial profiling’ by our critics [so be it] a close study of the family photographs above, Figures 6 to 13, does, in this new light, suggest that Pat and Joan’s father, Roderick, might well have had West Indian rather than Aboriginal features.

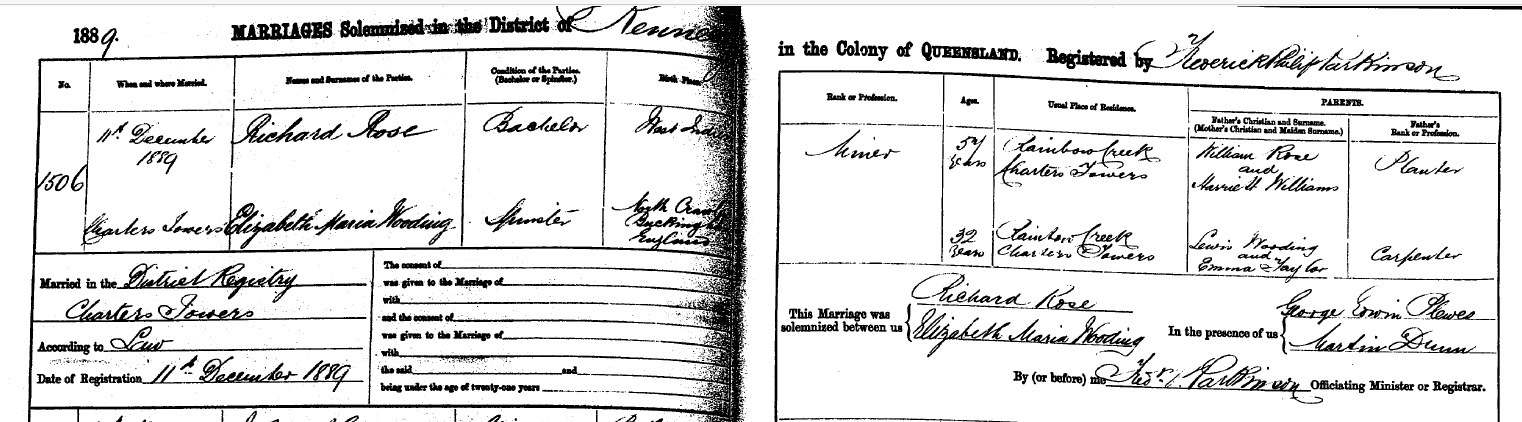

The genealogists now swung into searching the records for the name of a “Richard Rose” in Queensland and once again struck genealogical gold - a Richard Rose had married an Elizabeth Maria Wooding in Charters Towers, Queensland on 11 December 1889.

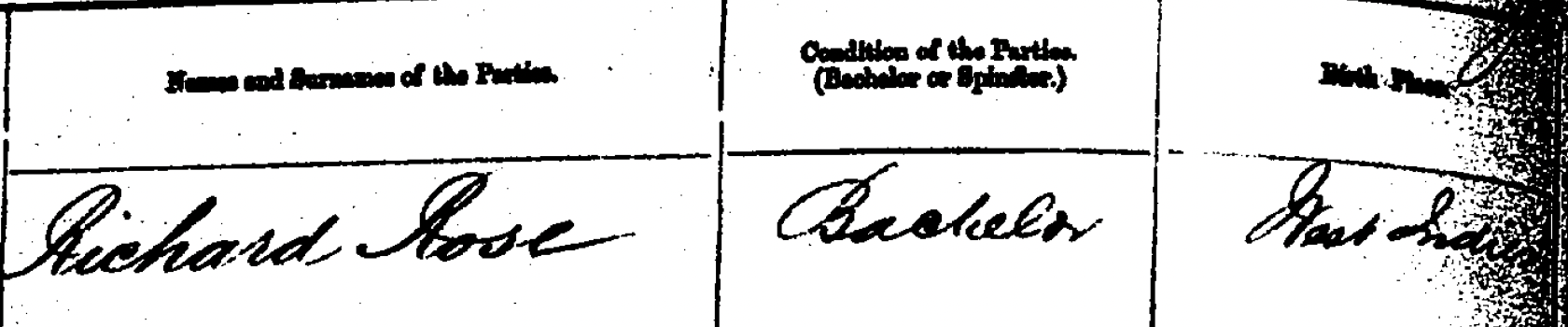

It was “our” Richard Rose because the groom’s details matched those of the Richard Rose on William Rose’s birth record: Richard Rose, Bachelor; Aged: 57 [i.e.born ca1832, ‘same’ as ca1831 on his son William’s birth record]; Profession: Miner [same as son’s birth record]; Birthplace: West Indies [same as William’s birth record]. The correlations were too close for it not to be the same Richard Rose (See Figure 16).

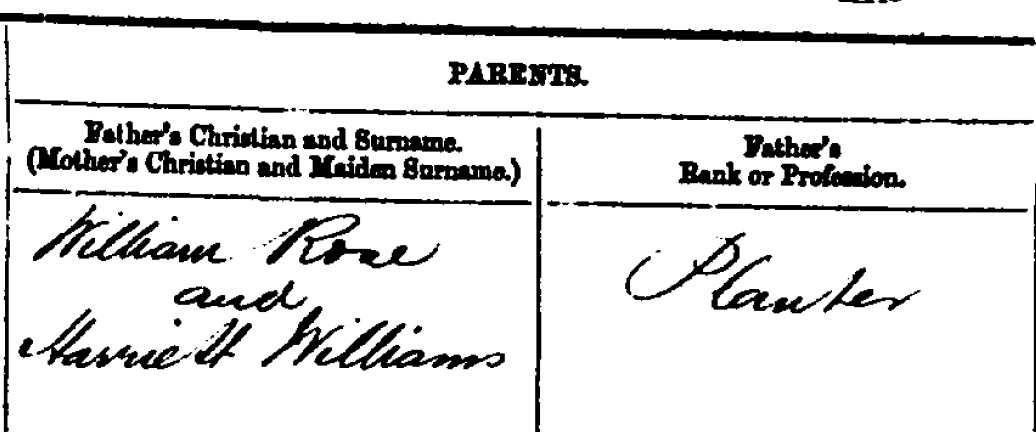

With the discovery of this marriage record however, the family history of Pat Eatock just got a whole lot more interesting - much more interesting than even Pat herself could have imagined. For, in the far right columns of the marriage record book, appeared the names of Richard Rose’s parents and his father’s Profession - that of “Planter” (Figure 15).

Figure 15 - Expanded columns of Richard Rose’s marriage record showing his Parent’s names and Father's Profession: William Rose, Planter; and Mother: Harriet Williams. Source QLDBDM# 1889/C/1186

Figure 16 - Extract from the 1889 Marriages Record book "Marriages Solemnised in the District of Kennedy in the Colony of Queensland" showing a marriage between West Indian born Robert Rose and the English born Elizabeth Maria Wooding: Date of Marriage: 11 December 1889; Place of Marriage: Charters Towers [Qld]; [Groom] Richard Rose, Bachelor; Aged: 57 [i.e. born ca1832]; Occupation: Miner; Residence: Rainbow Creek, Charters Towers; Birthplace: West Indies; Father: William Rose, Planter; Mother: Harriet Williams./ [Bride] Elizabeth Maria Wooding; Age: 32; Birthplace: North Crossley, Buckingham, England, Source: QLDBDM# 1889/C/1186

5. The Slavery Connection?

It is worth pausing for a moment to consider what these new revelations might mean.

Firstly, Richard Rose might have been the ‘white’ son of a West Indian planter family, who came to Queensland seeking his fortune - the father William Rose and the mother Harriet [Rose nee] Williams on his marriage record being both say, Scottish. If this was the case, he would have brought no ‘colour’ with him, so we are none the wiser as to where the Eatock’s, self-perceived ‘blackness’ may have originated from.

Alternatively Richard Rose might have been the result of a union between his ‘white’, planter father, William Rose, and one of the female domestics or slaves on the plantation, Harriet Williams, who most certainly would have been ‘black.’ Richard was born in ca1832, just before British slavery was formerly abolished in the empire so he could have been a slave himself. Was this the source of the ‘blackness’ in the Eatock family line?

Our genealogists were getting excited - were they about to open a secret door onto a whole new fascinating genealogical vista that no one in Australia had previously been aware of, not even the Eatock’s? Was the discovery of the real source of the Eatock’s ‘blackness’ - derived from a West Indian slave - about to turn the judgement in the Eatock v Bolt case on its head?

But before the project took on the huge expense in time and money, that delving into the genealogical records of the West Indies would entail, it was deemed prudent first for the researchers to make absolutely sure that they had in Richard Rose the man who really was the father of the boy, William Rose. And they also had to be one hundred percent certain that William Rose was really the one and the same as William Eatock.

And once again, as they say in Greece, “the Gods were smiling”, and the proof miraculously materialised.

6. The Mining Lease

On the 28th of June 1870, a miner walked into the Gympie Mining Warden’s office and lodged an application to transfer his mining lease on the goldfields. His name was Richard Rose and he had held a quartz mining claim on the New Monckland Reef No. 1A North in Gympie since 9 March 1868.

Figure 17 - Illustration of the Gympie Goldfield's at the time of Richard Rose. The fabulous gold fields at Gympie had only been discovered in October 1867

Source: The goldfields of Queensland : Gympie goldfield, 1868-1898, p2.

He now said he wanted to transfer his claim into the name of a four-year-old boy, a boy called Donald Eatock.

Donald Eatock had been born in 1866 and was the first son of Catherine Davidson. By endorsing this transfer, Richard Rose was essentially giving control of the mining lease to Catherine, the mother and legal guardian of young Donald.

But why would Richard Rose transfer this asset to the control of Catherine Davidson, who subsequently transferred (sold?) it, within three months of acquiring it, to a Riley Duckworth on 19 September 1870? (Figures 18).

Our readers will know why - because Richard Rose and Catherine Davidson had had a previous relationship. Although they never married, Richard was the father to Catherine’s younger boy, the one-year-old William Rose and, by this act of transfer, Richard was acknowledging this relationship, as well as at least some responsibility to the future welfare of both Catherine and his son William. Donald, the four-year-old, was chosen as the recipient rather than William, perhaps because William was still only a vulnerable baby, less than a year old.

This mining lease connection is thus documentary proof that there was a personal link between Richard Rose [a miner in Gympie, born in the West Indies] and the Eatock family - in this case Donald Eatock whose mother Catherine Eatock nee Davidson was also the mother to a boy born William Rose in Gympie and with a birth record to prove it. Ultimately, William Rose would acquire his mother’s married name and would go to become the Eatock family’s apical ancestor, William Eatock.

Figures 18A&B - An extract of the Index to Registers for Gympie Mining Warden - Gympie Mining Claims 1868-1901, showing the Richard Rose mining lease transfer. Source here Gympie Mining Claims 1868-1901 (Queensland Archives), p151, New Monckland No. 1A North, Claim No: 1935, Richard Rose, Miner’s Right #: 32928, Date: 4 March 1870, Transferred: 28 June 1870 to Donald Etock [Eatock]. Full page of book here

7. Eatock v Bolt - a Proven Miscarriage of Justice

The chain of documents presented so far therefore confirms that William Eatock, Pat and Joan’s grandfather, was born William Rose [b.1869 in Gympie] to a mother Catherine Eatock (nee Davidson) [born in Scotland] and a biological father Richard Rose [born in the West Indies]

William Eatock was really William Rose and was of West Indian and Scottish descent, not Aboriginal - and we now had his birth record to prove it (Figure 14).

This conclusion would normally justify the completion of the research project at this point, it now having been shown that the parents of William Eatock had both been born overseas, so William could not have been Aboriginal.

The consequence of this must therefore be that the Eatock v Bolt case was a miscarriage of justice because Pat Eatock had no standing in launching proceedings in the first place. She was not an ‘Aboriginal person’ by Justice Bromberg’s own definition.

Additionally, Pat Eatock’s non-Aboriginal genealogy has now been proven to the point of satisfaction of the Briginshaw Principle, a point that even her own counsel, Mr Merkel would concede. (See previous post, Part 1 - Merkel v Merkel - The Justice and the Advocate)

The final, alleged Family tree for Pat Eatock can now be presented (Figure 18C).

Figure 18C - Alleged Family tree for Pat Eatock. Full File for download here pdf and jpg

Disclaimer: This genealogical work has been undertaken in good faith and is based on the publicly available records. However, it cannot account for events which may result in Aboriginal ancestry entering into the family line such as via a private or unrecorded adoption of an Aboriginal child into the family, or a relationship out of wedlock between a family member and an Aboriginal person that produced a child of Aboriginal descent who was then incorporated into the family without record, or with a record that did not disclose the Aboriginality of that child.

But what would still be fascinating to know would be the answer to the question: Where is the evidence that Richard Rose was a ‘man of colour’?

This required the genealogists to open that secret door that led to the archives of the slave plantations of St Vincent and the Grenadines in the West Indies, and so they went through…..

8. A “Sliding Doors” Moment in Australian Historiography

In a hot, humid office on the island of St Vincent in the West Indies, the Registrar, John Beresford, was certifying a copy of the last Will and Testament of a local planter, William Rose.

It was the 21st of November 1838 and a “Sliding Doors” moment was in play that would ultimately influence Australian socio-political policy in the early 21st century in general, and the journalistic legacy of Andrew Bolt in particular, although of course no one in Beresford’s office knew, or even cared, at the time.

Some readers might find this hard to believe, but stay with me.

Beresford had been a busy man since the Slavery Abolition Act had been passed in Britain in 1833. The slave-plantation system in the islands of St Vincent and the Grenadines was being overturned and the planters were frantically getting their estates, paperwork and wills adjusted to cope with the new social and economic order.

One of Bereford’s clients, William Rose, who owned the Union Estate on the small island of Bequia (pron. bek-way) had received his 3,882 Pound Stirling compensation package in 1836, in exchange for the liberation of his 166 ‘negro’ slaves (Figure 20).

Figure 19 - Map of St Vincent and the Grenadines showing the island of Bequia (pron. bek-way)

Figure 20 - Excerpt of Reparations Record for William Rose of St Vincent - Union Estate. 166 Enslaved persons - 3882 pound sterling in 1836. Source

The will of William Rose’s provided the details of the impending “Sliding Doors” moment - for while some planter's had invariably taken their compensation money and run, leaving their slaves to fend for themselves, and other, more unscrupulous ones, had taken their compensation, but then still on-sold their slaves to planters outside the British islands, where slavery was still practiced [see Ref 4], those slaves on William Rose’s estate that he had fathered with slave women - all seven of them - were provided for when the will was proved in 1840, a year after his death.

His 8-year-old son, Richard Rose, was one of those seven child beneficiaries and it is fascinating to speculate that if William hadn’t left him the modest funds in his will that appeared to have allow Richard to escape the islands, become a seaman and make his way to a ‘new’ New World on the Queensland gold fields, then Richard would not have had a son, William Eatock, and ‘blackness’ would not have entered Pat Eatock’s family line.

Pat would then not have mistakenly, or some might say ‘opportunistically’, self-identified as a ‘black woman’, and an Aboriginal activist black woman in particular. And Andrew Bolt would not have been dragged to court, and defeated by an angry woman who Justice Bromberg had created a new ‘class’ category for, the ‘fair-skinned Aboriginal person.’

But then, as the executor read the will, William had not slipped through the “sliding door” that would have left his slave-children out of his will - instead William had decided to leave them funds for their care and education. So, as a result of his inheritance, Richard’s progress through life caused a series of events to unfold that were to lead to a turning-point in the free-speech and race relations of country, that was a continent and 200 years away:

“I William Rose of Bequia within the Government of Saint Vincent planter … bestow and bequeath my house … in Kingstown and all my plate linen and furniture of every description unto Charlotte Jardine [his wife] … and after her decease to my three children Elizabeth Grace and Georgiana [three of his legitimate and white children] to be equally divided….

I give my house in the town of Bequia unto my children Carrington, John and Mary [three of his illegitimate, ‘coloured’ children] their heirs and assigns for ever to be equally divided between them as tenants in common.

I give devise and bequeath all my other real and Personal Estate of what nature …Unto William Rose Scott , William M’Donald , Adam Stelly and Charles Shephard of Saint Vincent Esquires … in trust for the following purposes

first to pay all my just debts and funeral expenses and the charges of proving my Will

also to sell and dispose of my estate in Bequia with all convenient speed and to secure the sum of four thousand four hundred pounds Sterling in good security in the names of my said trustees for the benefit of my eleven children

and to pay to care of my four children Jane, Elizabeth, Grace & Georgiana [the ‘white’ issue from his wife] the sum of six hundred pounds sterling

and the sum of three hundred pounds sterling to care of my seven children Carrington, John, Mary, Elenora, Duke, Richard and Favorita [the ‘coloured’ issue from his slave women] as they respectively attain the age of twenty-one years or days of marriage and in the meantime the interest to be applied to their maintenance and education and the share of any child dying under age and unmarried to be divided among the survivors…etc etc “

- relevant extracts from the Last Will and Testament of William Rose jnr [d1839]. See Full Will in Figures 21 & 22; Extract showing Richard’s [Rose] name as a beneficiary in Figure 23 and our transcription attempt here

Figure 21 - Page 1 of The Will of William Rose, planter of Union Estate, Bequia, St Vincent, West Indies, proved on 1st June 1840. Source: PROB 11/1912/294

Figure 22 - Page 2 of The Will of William Rose, planter of Union Estate, Bequia, St Vincent, West Indies, proved on 1st June 1840. Source: PROB 11/1912/294

Figure 23 - Extract of The Will of William Rose, planter of Union Estate, Bequia, St Vincent, West Indies, proved on 1st June 1840 showing name of his ‘coloured’ son, Richard [Rose]. Source: PROB 11/1912/294

9. But Was the Miner from Gympie the one and the same Coloured Child-slave of Bequia?

Some readers might be thinking, “where is the real evidence linking the Australian Richard Rose with this particular Richard Rose, the slave-child beneficiary of William Rose’s will? Sure, they have the same surname, but where is the evidence linking them?”

It is true that even after much archival research, no document could be found that definitively linked Richard Rose, the son of William Rose of Bequia, St Vincent to Richard Rose the miner of Gympie, Queensland - no record showing his departure from the West Indies and his arrival in Australia, nor any supporting diary entry, letter, newspaper report or other correspondence to, or from, the West Indies has been was found to date.

However, the circumstantial evidence is very extensive, so extensive that the genealogists are confident to state that he is the one and same person. To support their belief, the genealogists provide the following evidence:

1) - Firstly, the traditional way the Scots often named children, followed a simple set of rules:

1st son named after father's father

2nd son named after mother's father

3rd son named after father

1st daughter named after mother's mother

2nd daughter named after father's mother

3rd daughter named after mother. [ Source Findmypast]

It does not prove anything but Richard Rose’s father’s name was William Rose [of St Vincent in West Indies] who was also of Scottish decent. Thus it would have been traditional for Richard to name his first son by Catherine, William Rose [Eatock], after his [the baby’s] father’s father, which is what occurred. This is just a very small piece of circumstantial evidence, but nice to have.

2) - The Richard Rose from Gympie stated on two records that he was born in “Kingston, St Vincent, West Indies” (Figure 24 - his son’s 1869 birth certificate) or that he was born in the “West Indies.” (Figure 25 - his 1889 marriage record to Elizabeth Wooding

Figure 23 - Extract from birth record for William Rose showing his father’s details - Richard Rose born in Kingston St Vincent West Indies. Source: Full file here

Figure 24 - Extract from marriage record of Richard Rose and Elizabeth Maria Wooding showing Richard’s birthplace as the West Indies. Source: Full File here

Figure 25 - Extract from marriage record of Richard Rose and Elizabeth Maria Wooding showing Richard’s parents as William Rose and Harriet Williams. Source: Full File here

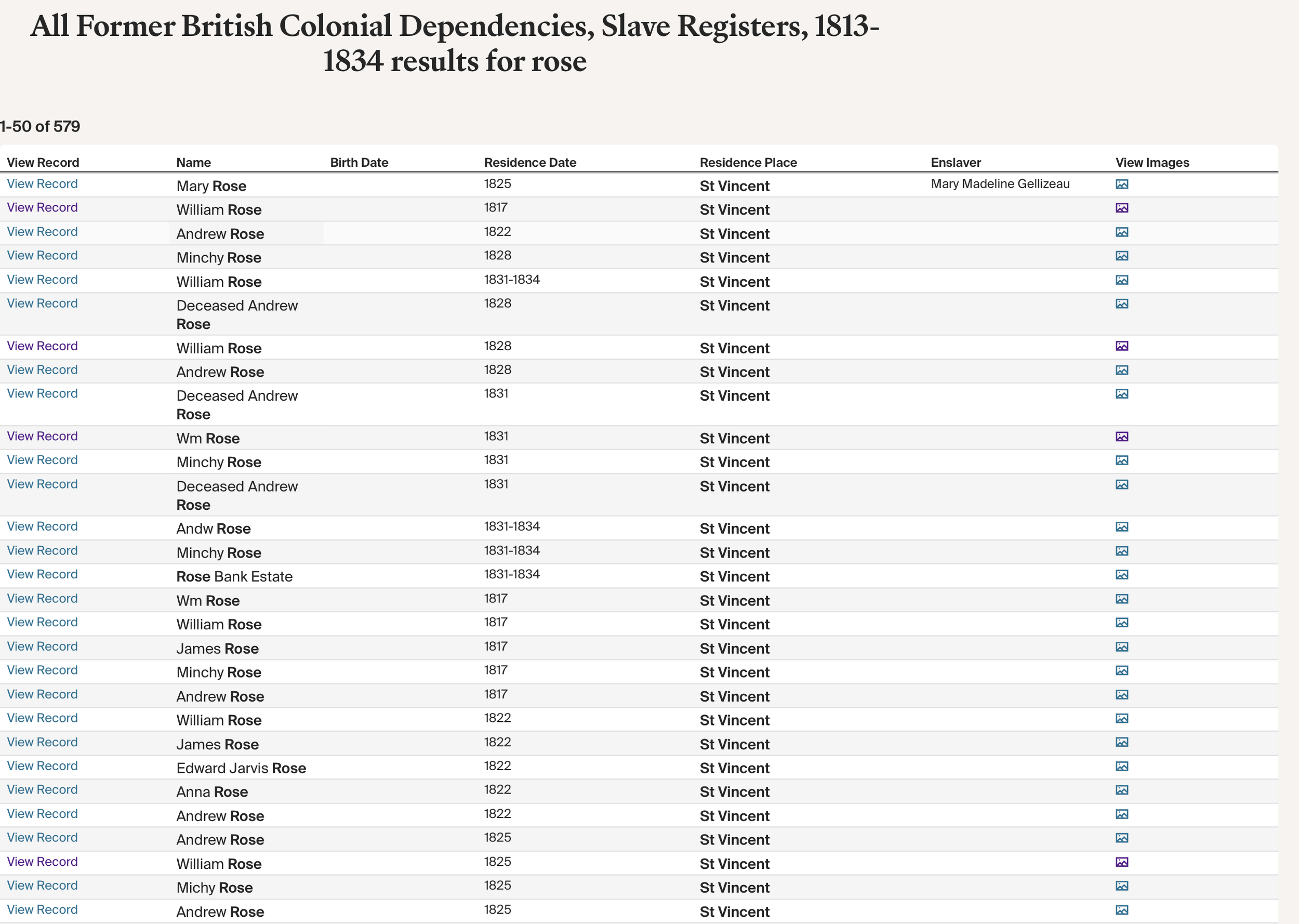

3) - The island community of St Vincent and the Grenadines was quite small in the 1800s so a search of all the slave and plantation records which were owned by a planter named “Rose”, although time consuming, was not so monumental that it did not produce results. The following listing was soon located:

Figure 26 - List of Slave Plantation Owners on the islands of St Vincent [includes the Grenadines i.e and Bequia] named “Rose” 1817 to 1834. Source: Ancestry.com

As per the listing in Figure 26, William Rose was a well known planter name - William Rose snr had established the Union Estate on the island of Bequia ca1781 [Ref 4]. When he died in 1817, the estate was inherited by his son, William Rose jnr, who himself died in 1839. All the references to “William Rose” in Figure 26 are related to one or other of these men, father or son. No other planters named William Rose in St Vincent were found in the archives.

These two men are also the only William Rose’s in St Vincent that appear in the records of the Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery database (Figure 27).

So the documentary evidence very strongly supports that a Richard Rose, who said he was born in Kingstown, St Vincent, West Indies, and whose father he said was a ‘planter’, is almost certainly the son of one of these two men. Because Richard was born ca1832, his claimed father must have been William Rose jnr, as the senior Rose had died in 1817.

Figure 27 - Extract of the Slave Plantation details for the only plantation owners in St Vincent, West Indies with the name “William Rose” - William Rose snr and William Rose jnr. Source: Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery

4) - The Gympie miner, Richard Rose was recorded as being born around 1831 or 1832 [based on marriage record and William Rose’s birth record].

The Registry of Slaves on the Union Estate of William Rose, which lists the names, ages and occupations of the slaves held by William Rose in 1834 is available. It records a “Richard” as being a child whose age is “Under 6 years” (Figure 28, near bottom first column). This correlates, as the “Gympie” Richard Rose would have been 2 or 3 years old in 1834.

Figure 28 - “Registry of Slaves made up on the 31st of May 1834 on the Union Estate of William Rose by himself", p192. Source: Ancestry.com . Full File download here

5) - The registry also lists a female slave by the name of Harriet, aged 27 years, occupied as a domestic (Figure 29, fourth column near bottom).

Figure 29 - “Registry of Slaves made up on the 31st of May 1834 on the Union Estate of William Rose by himself", p191. Source: Ancestry.com . Full File download here

6) - The Gympie Robert Rose recorded his parents to be William Rose (planter) and Harriet Williams (see Figure 25). The slave list records the domestic slave as Harriet by first name only - her surname is omitted so we have no way of knowing for certain that it was Williams.

However by the following circumstantial evidence and reasoning it is more than likely that she is Harriet Williams, and mother of Richard Rose. Thus, the young Richard Rose listed here as a slave-boy went on to become the ‘Gympie Richard Rose’, father to the William Rose who ultimately became William Eatock, Pat Eatock’s grandfather.

Additional circumstantial evidence is provided by a careful analysis of these two pages of the slave’s list, plus other related documents (see British Merchant Seaman records below). What is revealed is:

a) - Most of the slaves 7 years and older have an occupation attached to their name - labourer, vine gang, carpenter, sailor, etc. This implies they were slaves working in the fields or workshops on the estate. A few including Harriet are listed as domestics, implying they worked in the household. This implies that Harriet would be in a position within the household where William Rose could maintain a ‘relationship’ with her.

b) - There are a number of slaves that have no occupation listed - Duke (aged 7), Alexander (6), John (6), Carrington (9), Manny (10), Anne (11), all the children under 6 years including Richard and Mary. The names in bold also appear in William Rose’s will as being part of his group of seven children [presumably the issue from his relationship with slave women] - Carrington, John, Mary, Elenora, Duke, Richard and Favorita.

This suggests that these children were not put to labour , but were perhaps schooled.

c) - There are no passenger list records for Richard Rose arriving in Australia. It is most likely that Richard arrived as a crew member on a ship [see below] but crew lists for vessels arriving and departing Australia were rarely kept, which could account for Richard Rose not being found in passenger lists.

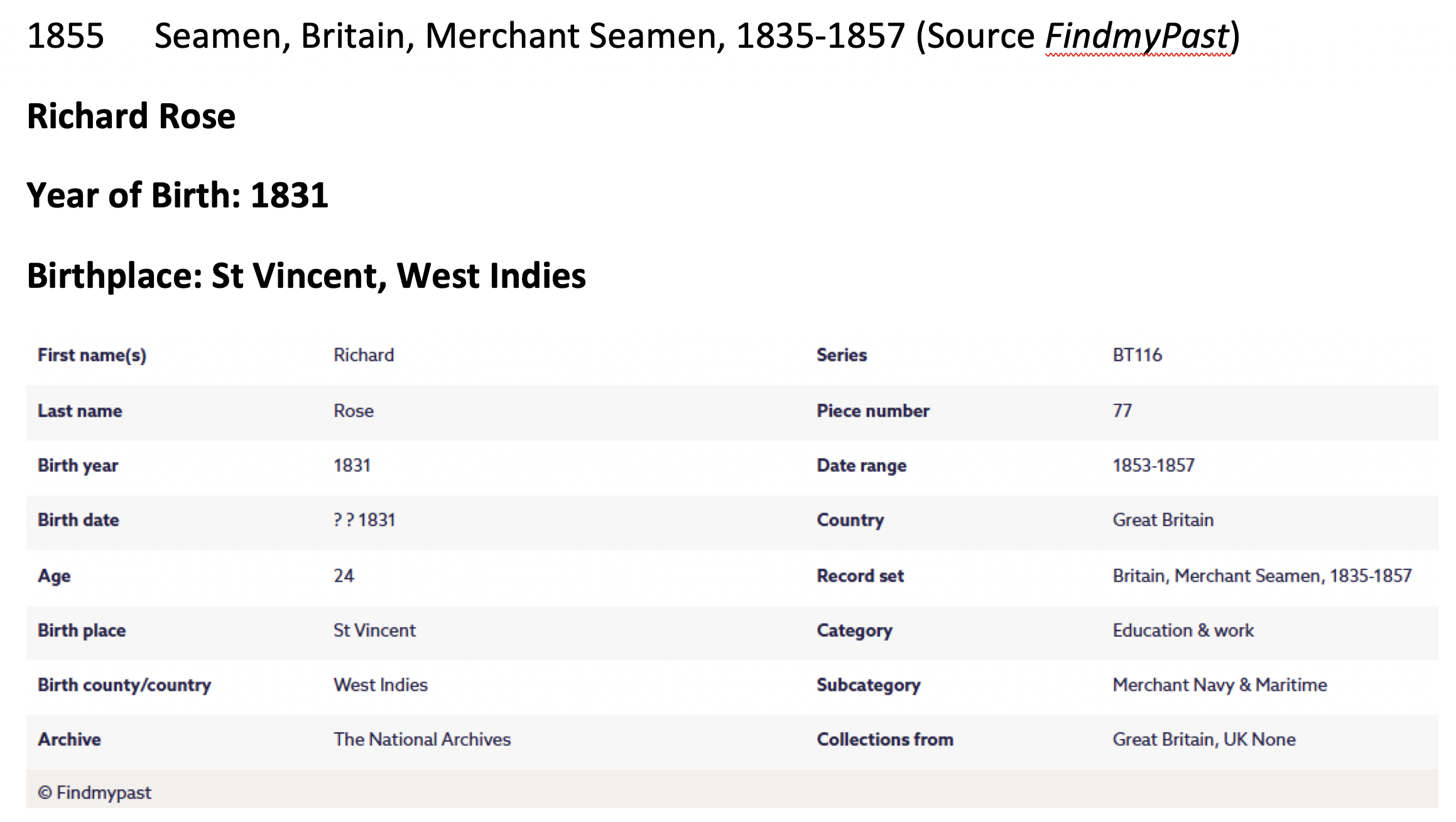

However, an entry for a Richard Rose has been found in the 1855 British Merchant Seamen records [when he was 24-years-old], which would account for Richard being a crew member on a ship rather than a passenger.

Figure 30 - Details of the British Merchant Seaman record (See Figure 31) for Richard Rose, believed to be the same Richard Rose as the son of William Rose jnr. Richard’s date of birth matches that on William Rose’s slave list, i.e. ca1831/2

Figure 31 - Extract of the British Merchant Seaman record for Richard Rose, believed to the same Richard Rose as the son of William Rose jnr. Richard’s date of birth matches that on William Rose’s slave list, i.e. ca1831/2. Source: Findmypast

This Richard Rose, the seaman, is more than likely ‘our’ Richard Rose given that it is highly unlikely that the small community of Kingston would produce two locally born men, both called Richard Rose, both born ca1831/2 and both becoming a British merchant seaman.

Additional, corroborating evidence was found that appears to show that one of Richard’s brothers [half or full?], Duke Rose, also became a British merchant seaman (Figure 32 & 33). The age of the ‘Duke’ in the slave-list is ‘7 years old’ in 1834, which puts his birth date ca1827 (Figure 28). This matches (in genealogically acceptable terms) the birth year of the ‘Duke’ in the seaman’s record (1828), which supports the notion that they are the same person named Duke.

Figure 32 - Details of the British Merchant Seaman record (Figure 33) for Duke Rose, the ‘boy of color’ and most likely the mulatto son of William Rose jnr, the St Vincent planter. Duke’s date of birth matches that on William Rose’s slave list, i.e. ca1828 and a “Duke” appeared in William’s will (see above).

Figure 33 - Extract of the British Merchant Seaman record for Duke Rose, the ‘boy of color’ and most likely the son of William Rose jnr, the St Vincent planter one of the estate’s slave women [Duke is on the list of slaves]. Duke’s date of birth matches that on William Rose’s slave list, i.e. ca1828 and a “Duke” appeared in William’s will (see above). Source: Findmypast

d) - Is this the ‘Colour’ Link?

Very noteworthy is the British Merchant Seaman entry for Duke Rose (Figures 32 & 33). It is more detailed than the one for his likely half or full brother, Richard, and it describes Duke’s ‘Complexion’ as: ‘Boy of Color’

This is the closest mention so far that we have had that these seven children of William Rose - including Duke and Richard - were ‘coloured’ or, in the terminology of Pat Eatock, had ‘black faces.’

Based on all this circumstantial evidence, the genealogists and researchers undertaking this work have concluded that Pat Eatock’s grandfather did carry ‘colour,’ a ‘blackness’, that he inherited from Richard Rose, his father and Pat Eatock’s biological great-grandfather.

So, rather than imagining her ancestors living in a simple ‘gunya’ [see 00:35] out on the Queensland frontier, Pat actually should have rather seen her ‘roots’ as having been depicted in this ‘family portrait’ painting from the 18th century Casta School of colonial paintings in the slave-society of Spanish Mexico.

Oppressor or oppressed muses the ghost of Pat - do I pay reparations for slavery or do I collect?

Oh, the irony!

Figure 34 - Imaginary, portrait of Pat Eatock’s ancestral ‘black’ family - 2X Great-grandfather William Rose, the owner of the slave plantation, the Union Estate in Bequia, St Vincent, West Indies, is attended to by his young son, Richard Rose, Pat Eatock’s great grandfather, while Pat’s 2X Great-grandmother, Harriet Williams, looks on lovingly. Unknown artist, after the Casta School

Conclusion

This now concludes the three part series on Revisiting Eatock v Bolt.

With hindsight, this whole saga looks like a total waste of a huge amount of the nation’s time, attention, money and legal and media resources. The case was built on a fabrication - that Pat Eatock was an ‘Aboriginal person’ - that would sadly lead to an explosion in the number of new, ‘fake’ Aborigines appearing [many of them subsequently exposed on this web-site], safe in the knowledge that no one ever again would have the courage to challenge their ancestry.

But perhaps worst of all, in my opinion, this notorious legal case was akin to a satirical ‘Passion Play’, where certain political and activist forces appeared to have colluded to ‘crucify’ the voice and opinions of Andrew Bolt for daring to question the categorization and division of Australians based on race, and what that might means for ‘special privileges’ to those of that new, anointed race.

The characters on stage were cast perfectly. One shouldn’t speak ill of the dead, but Pat Eatock’s performance as the aggrieved Aborigine was an Oscar-winning performance. Pat’s ability to morph from the working class, rat-bag and teller of tall stories that she was, to give the impression of being a ‘blak’ victim seeking justice from the powerful Murdoch Media empire, was truly a marvel to watch.

Pat’s ‘con job’ was ably assisted by her leading man, Ron Merkel, definitely a nominee for Human Rights Commission Oscars - Best Male Supporting Actor, Fantasy Category [‘Law Variety’ reports that some have alleged that Ron waived his usual eye-watering acting fee in the hope of winning the HRC Oscar - Bravo! for Ron and the future of virtue-signaling I say!]. If his tireless, behind the scenes lobbying to get his latest Passion Play, Eatock v Bolt, into the Fed Theatre was a secret plan for him to get a shot at the big award, then it succeeded admirably with his winning the HRC’s top Oscar award that year. Well done Sir Ron!

Ron’s performance was solid, and confirms his ability to handle genuinely praiseworthy roles, such as his 1998 performance in Shaw v Wolf, also at the Fed Theatre, where he gave a fine performance of the Briginshaw Principle in deciding who is and who isn’t Aboriginal.

In this latest play, Eatock v Bolt, which was confusingly promoted to the public as a court-room drama, but actually turned out to be in a category of all of its own - a tragic fantasy comedy - Ron gives a fine acting performance by throwing ethics and principles to the wind as the white-haired, old wizard, possessor of a wand that turns a white grandmother into a ‘fair-skinned’ Aboriginal elder.

That apt Maugham quote springs to mind to describe Ron Merkel’s character, the wizard, in his HRC Oscar winning performance:

You can't learn too soon that the most useful thing about a principle is that it can always be sacrificed to expediency.

- Somerset Maugham, The Circle, 1921

Roger Karge, Editor, Dark Emu Exposed

Ref 1. Eatock v Bolt 2011 judgement here

Ref 2. TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS,

Day 1 MELBOURNE, 10.16 AM, MONDAY, 28 MARCH 2011, FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA, VICTORIA REGISTRY, BROMBERG J, Eatock v Bolt

MR R. MERKEL QC appears with MR H. BORENSTEIN SC, MS C.M. HARRIS and MS P.C. KNOWLES for the applicant; MR N.J. YOUNG QC appears with DR M.J. COLLINS for the respondents

Ref 3. EVIDENCE ACT 1995 - SCHEDULE Oaths and Affirmations, Subsections 21(4) and 22(2)

Affirmations by witnesses:

I solemnly and sincerely declare and affirm that the evidence I shall give will be the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth. Source

Ref 4. See Biographical Sketch of Edward K. Biddy [ great-grandson of William Rose snr] – link to document download