Professor Jakelin Troy's Connection to Ngarigu Country - as Pioneering Settlers - Part 3

Figure 1 - University of Sydney’s Indigenous Ngarigu woman, Professor Jakelin Troy. Source

Jakelin Troy is a Ngarigu woman from the Snowy Mountains of New South Wales, and Director of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Research at The University of Sydney

In Part 1 and Part 2 of our research project into the Indigenous history of Ngarigu Country, we have used the remarkable family history of Sydney University’s Indigenous Professor, Jakelin Troy as our guide in trying to find a working definition of who really is, and who really isn’t, ‘Aboriginal’ in a political sense in modern Australia.

This is no longer an academic pursuit. With the Voice to Parliament very much back on the political and constitutional agenda after the recent federal election success of the Australian Labor Party, a political definition of who is an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, and therefore eligible to vote in Voice elections, will be essential for the legitimate functioning of the Voice process.

We consider Professor Jakelin Troy an excellent proxy for these discussions given her public service role as an academic, her employer’s endorsement of Reconciliation and the Uluru statement, her willingness to offer information regarding her family’s ancestors and history on her Ngarigu Country, and the wealth of publicly available information regarding her extensive family, which she implies provides her with Indigenous descent.

Nevertheless, to enter into questions of a person’s identity and motivations it is hard to avoid being accused of the ad hominem but, in the following discussion, more than enough valid argument will be provided to defend us from this charge.

In Part 1 of our series we found that Professor Jakelin Troy was wrong when she said was related to Jim Troy, a possible Indigenous candidate for the character on whom Banjo Paterson modelled The Man From Snowy River.

In Part 2 of our series we explored her mother’s family tree, the Beeds, but we were unable to find any evidence that this branch of Professor Troy’s family were in fact Aboriginal, with cultural, linguistic and spiritual connections to the tribal Ngarigu Country.

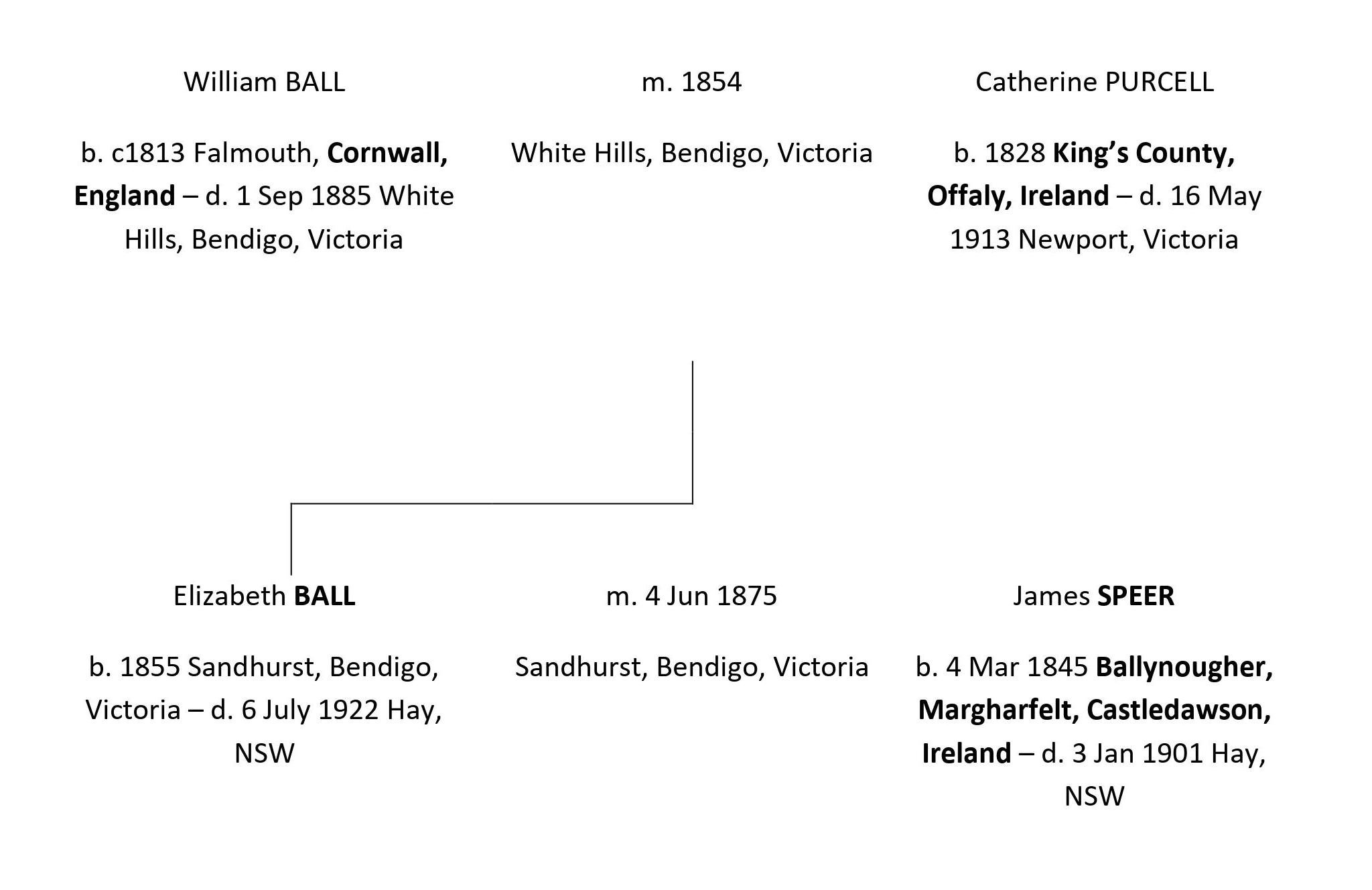

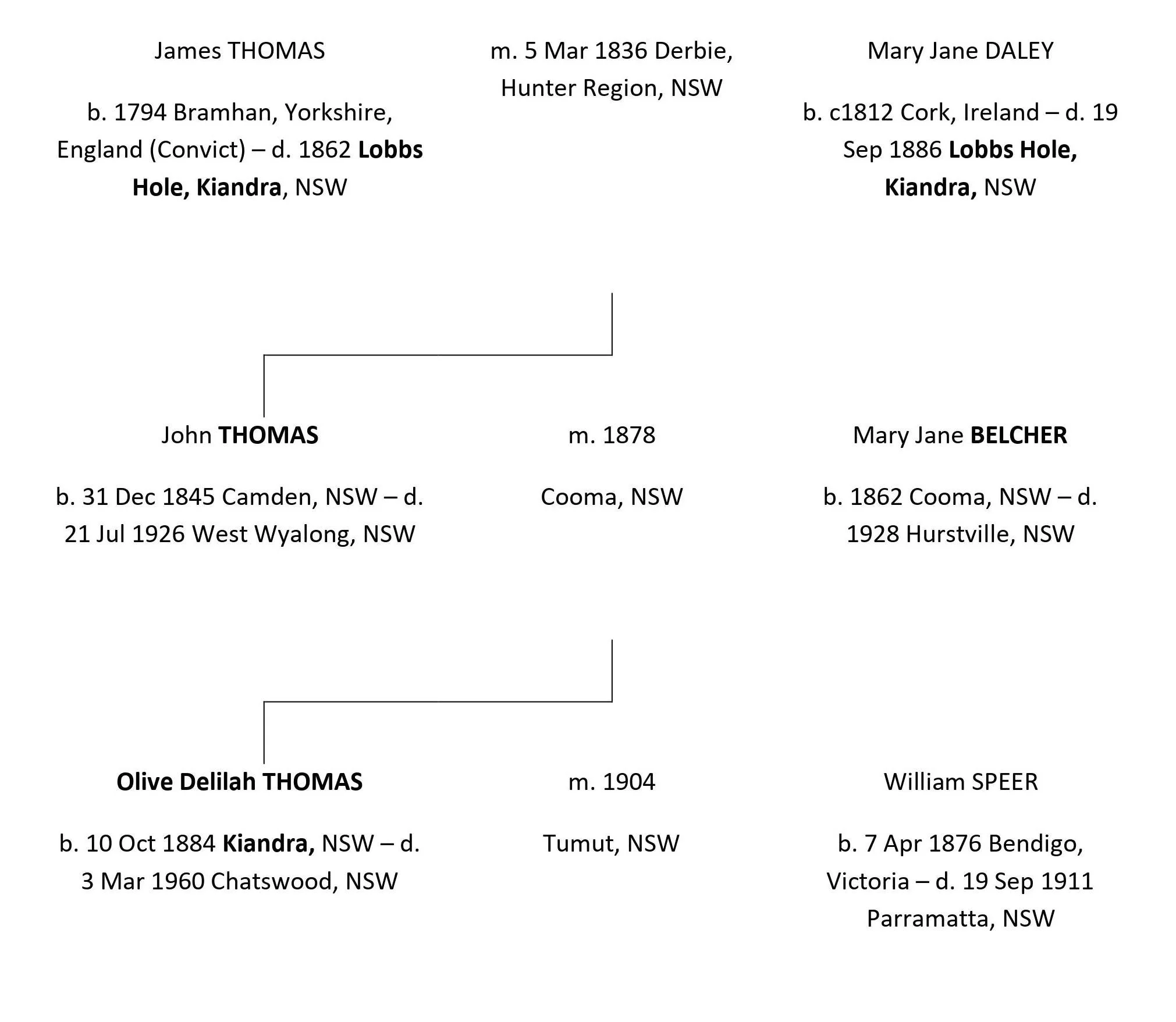

In this Part 3, we will now investigate the Speer branch of the family tree of Professor Troy. Professor Troy implies that her grandmother Sylvia Speer was Indigenous and ‘loved this [Ngarigu] Country and knew it all’. Will the Speer family and its sub-branches provide evidence of the ‘connection to Country’ to which Professor Troy speaks? Will the Speers be of Aboriginal descent? Will the descendants of the Speers be privileged to vote in the Voice elections?

Professor Troy’s Beloved Grandmother, Sylvia Elizabeth Olive Speer

Sylvia Elizabeth Olive Speer was born on the 12th January 1905 in the South-Western NSW town of Hay, as was recorded in the Hay-based newspaper, The Riverine Grazier. Syliva Speer married Henry Beed, and they had a daughter Shirley, Professor Jakelin Troy’s mother. Professor Troy confirms this in her PhD acknowledgement to her grandfather Henry Beed, and in her 12 January 2021 Facebook 116th anniversary commemoration of the birth of her grandmother. Sylvia Elizabeth Olive Speer’s position in the Speer family tree is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 - The Speer Family Branch of the Family Tree of Indigenous Professor Jakelin Troy and her mother, Shirley Troy/King (nee Beed).

Very interestingly, we see that Sylvia’s mother, Olive Deliah Thomas was born in Kiandra in 1884 and she was married in Tumut in 1904. Both these towns are on ‘Country’ in the Ngarigu tribal lands. In her Facebook post of 2021 Professor Troy speaks of her, ‘Kiandra the high plains of my Country, Ngarigu …’

Finally it seems we have located some ancestors of Professor Jakelin Troy who indeed were born and lived on ‘Country’.

But were they Aboriginal? Did they have a claimed unique connection to ‘Country’?

Was Olive Deliah Thomas, Professor Troy’s great-grandmother, the Indigenous ancestral link that the Professor relies upon to provide the love of, and a deep cultural, linguistic and spiritual connection to, her Ngarigu country?

Could the University of Sydney now be assured that Professor Jakelin Troy satisfies the ‘3-part rule’ for Aboriginality, with her great-grandmother Olive providing the necessary component of ‘Aboriginal descent’?

Sadly not.

In fact, Olive Deliah Speer (nee Thomas) was to prove a most remarkable and praiseworthy woman, a descendant of pioneering colonial stock - a highly successful example of the ‘pioneering’ and the ‘colonial’ projects. These family tree branches of the Speers and the Thomas’s, were undoubtably a great influence on young Miss Shirley Beed, when she wrote in her prize-winning 1943 essay,

‘… Tumut was made known to ambitious settlers and many people turned south [from the Sydney district]. In 1830 the first white child to be born in the new locality was at Darbalara. The pioneers of these parts of the Colony were wonderful people, who make one proud to think they were our ancestors…The aboriginals were troublesome and savage and were always causing trouble ...’

- Miss Shirley Beed, from paragraphs two and three in her essay on the front page of the Tumut and Adelong Times, 16 march 1943 Source: The Tumut and Adelong Times, Tue 16 Mar 1943, p1. Full essay here

It seems that Professor Troy’s mother Shirley was fully aware of her family’s pioneering and colonial past.

Olive Deliah Speer (nee Thomas) - Professor Jakelin Troy’s great-grandmother

Olive was born in relative obscurity in 1884, ‘in a remote valley deep in the Snowy Mountains at Lobs [Lobbs] Hole’ (see Biography below), which is on the road to Kiandra, or as as Professor Jakelin Troy might prefer to describe it, ‘on Ngarigu Country’ at Kiandra.

However, by the 1930s under her second married name, Matron Olive Angermunde had become almost a house-hold name in Sydney where she was feted, by the rich and well-connected, and in the press, for her extraordinary nursing skills, political activism and organisational skills in fund-raising for the poor and needy.

Figure 3 - Matron Olive Angermunde [nee Speer, Thomas] ca1932. Source Entry 1903

The Croker Prize for Biography is a competition for members of the Society of Australian Genealogists who submit a researched biography of one of their own family members. In 2019, the prize called for submissions under the theme of, ‘A Woman of Influence’.

Entry Number 1903 was by a genealogist with a familiar surname, Terry Beed.

His submission was an excellent and detailed biography of one Olive Deliah Angermunde (1884-1960) titled, Newtown’s Noble Woman. His entry to the Croker competition met the conditions of the competition, namely that he had to be related to the subject - in fact she was his grandmother, just like she was a grandmother to Shirley Troy (nee Beed)

In fact, Terry Beed was the brother of Shirley Beed and therefore an uncle to Professor Jakelin Troy. This is corroborated by their own mother’s death notice (Sylvia Beed) where the names of both Terry and Shirley are listed as two of her children (Figure 4).

Figure 4 - Death notice for Sylvia Beed (nee Speer) mother to both Shirley Troy (nee King, Beed) and Terry Beed. Sylvia was the daughter of Olive Delilah Angermunde. Source The Sydney Morning Herald, 3 May 1980, p132

Terry Beed provided a lot of detail in his biography on the fascinating life of his grandmother, Olive Deliah Thomas, whose,

‘first and second marriages came to an early end with the untimely deaths of her first husband after 7 years of marriage (William Speer, NSW Death Registration 1911/011667) and her second after only 8 years (Theodore Angermunde, NSW Death Registration 7277/1923) … Olive did not marry again until 1947 (NSW Marriage Registration 12514/1947’ [to William Forsythe McMiles];

Terry Beed’s biography of his grandmother, who is Professor Jakelin Troy’s great-grandmother, can be read here. A presentation of his biographical work was also presented at the Australian Society for the Study of Labour History, 16th Biennial Conference Trades Hall, Perth W.A. 3 – 5 October 2019.

At no point in Terry Beed’s biography of his grandmother does he imply, or provide any evidence, that she has any Aboriginal descent.

All the Speer ancestral lines go back ultimately to Ireland (Figure 2) and Elizabeth Ball’s ancestors go back to Ireland and England (Figure 5). Therefore, there is no indication in this line of the Speer and Ball family tree that there is any Aboriginal ancestry.

We can therefore conclude that Shirley Beed and her daughter Professor Jakelin Troy have no Aboriginal descent by this line.

Figure 5 - Elizabeth Ball’s ancestors go back to Ireland and England. These are direct lines for Professor Jakelin Troy’s ancestry and do not indicate any Aboriginal descent at all.

To determine whether Olive Deliah Thomas had any Aboriginal descent from her Thomas line of ancestry, we checked the family tree of her father, John Thomas and her mother, Mary Jane Belcher. We found no indication of any Aboriginal ancestry in John Thomas. His father had been born in England and arrived as a convict and his mother was born in Ireland. Interestingly, both of his parents died ‘on Ngarigu Country’, at Lobbs Hole, Kiandra.

Olive Deliah Thomas’s mother, Mary Jane Belcher, likewise appears to have no Aboriginal ancestry - her father John Belcher being born in the USA, and her mother, Fanny Nancarrow in Ireland, although she too died ‘on Ngarigu Country’ in Kiandra (Figure 7).

Figure 6 - The family tree of Olive Deliah Thomas (Matron Angermunde), Professor Troy’s great-grandmother.

Figure 7 - Family tree of Mary Jane Belcher, who was the mother of Olive Deliah Thomas and thus great-great-grandmother of Indigenous Professor Jakelin Troy

At this stage of our story, our readers might be wondering if Professor Jakelin Troy is merely making her claim that,

‘Kiandra the high plains of my Country, Ngarigu … Shirley Troy our Country and today is my grandmother’s birthday she loved this Country and knew it all’

is based solely on the fact that her ancestors in this region were colonial pioneers and settlers. They were some of the earliest settlers, to arrive at Lobbs Hole Kiandra, to be born there, live there and to die there. But they were not Aboriginal people.

We have been unable to find any records showing any Aboriginal ancestors in these branches of Professor Troy’s family tree.

The photographic records also provide some corroborating evidence that these branches of Professor Troy’s family tree were good, solid pioneering and relatively respectable, settler people. Reluctantly, we need to use the parlance of the new Apartheid times in which we find ourselves today and note that they were also white, with their ancestors easily traced back to the white societies in Britain, Ireland and the United States.

Figure 8 - Professor Troy’s great-grandmother, Matron Olive Angermunde (left, ca1932), her grandmother Sylvia Beed (neeSpeer) (middle, ca1940s?) , herself with her mother Shirley Troy (King, nee Beed) (right, 2013). Photo sources - Olive (Terry Beed ‘s biography), Sylvia (Ancestry user bwall9999 originally shared this on 01 Mar 2014), Jaky & Shirley (Lyn Mills, Source.)

Figure 9 - No photo is available of William Speer, Olive’s first husband and Professor Troy’s great-grandfather who died in 1911, aged 35 years. This is a photo however, of his brother James Speer, who shared the same mother and father, and who was 4 years younger than William. James is in the back row, far right. He was an Alderman in Hay from the early 1920s and served for 22 year. Source - Ancestry user bwall9999 originally shared this on 09 Feb 2014. See also Note 1 in Further Reading.

The pioneering spirit of Professor Troy’s ancestors is well illustrated by her great-great-grandfather John Thomas (Olive Deliah Thomas’s father). An illuminating obituary appeared for him on the front page of The Wyalong Advocate on 23 July 1926.

Figure 10 - Said to be a photograph of John Thomas, pioneer of Kiandra and father of Matron Olive Angermondy [sic]. He was the great-great-grandfather of Professor Jakelin Troy. Source - Ancestry user centre41 originally shared this on 18 Jul 2017

Figure 11 - Burial plaque for pioneer John Thomas.

A PIONEER PASSES - Death of John Thomas

The death of Mr. John Thomas, which occurred at the residence of his son (Mr. C. J. Thomas) on Wednesday last, removes one of the oldest and most respected residents of the district and one who was identified with the early pioneering days of the State. He was 81 years of age, but retained all his faculties and was remarkably active right up to the time of his death. He suffered from bronchitis during the winter, and about noon on Wednesday last, he complained of feeling faint, and was caught by his son Len who put him to bed. He remained conscious for a few minutes, then lapsed into unconsciousness and died peacefully.

The late Mr. Thomas was born at Camden in 1845. When he was 13 years of age, he used to accompany his father on long treks with bullock teams from Circular Quay, Sydney, to the various goldfields with provisions, notably Beechworth. (Victoria), Tumburrumbah, Morockle, and Kiandra.

In 1860 he selected land at Kiandra, and followed grazing pursuits there till he came to the Wyalong district in 1913. He could tell some very interesting stories of the early mining and bushranging days, and the hardships and difficulties which the early colonists had to contend with. Of a quiet, unassuming but kindly and generous disposition, the late Mr. Thomas bore the hall-mark of the sturdy pioneers who have developed the outback portions of the State. He was a regular attendant at St. Barnabas' Church of England, and rode his horse to Church as usual last Sunday night.

The Rev. W. J. Conran held a short service at Mr. C. J. Thomas' residence on Thursday, after which the remains were convoyed to the railway station and entrained for Tumut, to be interred alongside those of his late wife. The local funeral arrangements were conducted by Mr. Mills.

Deceased was twice married. The sons and daughters of the first wife are Mr C. J. Thomas, West Wyalong; Nurse Angermondy, of the Royal Hospital for Women, Sydney; and Mrs. B. Bellingham, of Muswellbrook. The sons of the second marriage are Harry, of Goulburn, and Leonard, of West Wyalong. [But as is often the case in Life, there was a twist - see our next post in the series on John Thomas] [Death NSWBDM# 15459/1926]

So there you have it, Professor Jakelin Troy is correct to claim that her family does have a deep connection with the high-plains of Kiandra and the region where the Ngarigu Aboriginal people traditionally lived. But as the Speer, Thomas and Beed branches of her family tree show, this family connection was as colonising pioneers and selectors (Note 3). Her ancestors from these family branches concentrated around Lobbs Hole near Kiandra and also in Tumut.

These ancestors from this part of her family tree were white. The Ngarigu Aboriginal people at the time were on their own path to integration and assimilation into the new Australian society that was developing on their traditional Ngarigu land. The Ngarigu Aboriginal people were well established and recognised in the area as shown in Figure 12. If Professor Jakelin Troy’s ancestors from these Speer, Thomas and Beed branches were part of this local Aboriginal Ngarigu society we would most certainly find some mention of them in her family history, in the local newspapers or in government records. We found none.

As the photographs of her family from these branches show, they don’t seem to look anything like the real Ngarigu people who were living there at around the same time. In fact, there is no mention anywhere that we could find that says these Kiandra-based branches of Professor Troy’s family tree had any Ngarigu [Ngarigo] ancestry.

Figure 12 - These Ngarigu [Ngarigo] people were photographed at around the time Professor Jakelin Troy’s pioneering settler family were being born, living and being buried on Ngarigu Country. Source

But our investigations do not end here.

As we dug deeper into Professor Troy’s remarkable family tree and all its branches, some fascinating stories began to emerge, which we will discuss in our next post.

Notes and Further Reading

Note 1 - The following biographical details were located on James Speer who was William Speer’s brother.

Figure 13 - Source: Ancestry user bwall9999 originally shared this on 09 Feb 2014

Note 2 - Local News 1942

Figure 14 - The Riverine Grazier, Tue 11 Aug 1942 , Page 4 , Doings in Different Districts

Note 3 - Is Professor Troy Indigenising Her Family’s Past ?

In 1956, Professor Troy’s great grandmother, Olive Angermunde provided details on her family history deep in the Snowy Mountains. Of her father it was noted in this 1956 report, The House on Sheep Station Hill (1884-1956), by Margaret Hudson for the COOMA-MONARO EXPRESS of 30 AUGUST 1956, that,

‘Seventy years ago, the sheltered valleys of the Yarrongabilly River supported one of the many lusty pioneering communities that toiled and sweated their way through Australia's early history. The soft deep folds and sheer rock walls of the surrounding hills echoed with the crack of whips and the ring of axes; the rivers were splashed with and muddied with the crossing and recrossing of bullock teams; and the gravel and rocks of the valley floor were crushed and washed for gold. And in the mornings, the warmth of the sun spreading from the mountain ridges down to the pastures below brought to these courageous people a deep love of the valley that was their home.

The valley sheltered them; the valley provided water and food for their stock and timber for their homes …

One of these early settlers was John Thomas of Camden who came to Lobs Hole in late in the 1840's [Olive Angermunde’s father and Professor Jake;in Troy’s great great grandfather]’ - (see also our Part 5 post )

But sixty-odd years later in 2019, Professor Jakelin Troy now describes her feelings as Indigenous First People person when thinking of the disrespect for trees by ‘the invading British,’

The last time I went back to my Country in the Snowy Mountains, I noticed tree after tree felled, chopped down seemingly without thought.

For me, it was unfathomable. First Peoples worldwide have fundamentally and always understood trees to be community members for us – they are not entities that exist in some biological separateness, given a Linnaean taxonomy and classed with other non-sentient beings. Trees are part of our mob, part of our human world and active members of our communities, with lives, loves and feelings … Trees provide us with inspiration for our art and give us the aesthetic of the landscape. When the invading British, as one of their first acts on our Country, cut them down, we wept and cried with the trees, sharing their pain and shielding them with our bodies.

When we destroy trees, we destroy ourselves. We cannot survive in a treeless world … Scientists conceive they know more about trees and plants because they study them and give them scientific names. We, the indigenous peoples of the world, have a deep-seated understanding of what this foreign science means. However, we understand it without disconnecting ourselves from the plants and trees around us.’ - The Guardian 1 April 2019

Professor Troy’s Guardian piece was published on April Fool’s Day 2019 - it has to be a joke yes?

In true Bruce Pascoe Dark Emu style, she is just making all this up, isn’t she?

Her pioneering Thomas ancestors were heavily involved in cutting down trees to provide the wood for their huts, stock-yards and for use in the mines. They also cleared the land to establish pasture for their stock. More recently, her Beed and King ancestors were involved in setting up one of the first ski lodges at Thredbo, with all the intended destruction of trees that entailed to establish the buildings, roads and ski runs.

But now she expects us to believe she is a weeping Indigenous First Nations woman who thinks, ‘when we destroy trees, we destroy ourselves.’

But if we don’t destroy the trees Jaky, how are the ‘snow-bunnies’ going to be able to hit the slopes of ‘The Great Snowy Hypocrisy Ski-Run’ at Thredbo, and then retire for drinks on the family ski-lodge balcony to admire the view of the cleared mountain-side runs?