The $5000 History Prize is Still Unclaimed - Correspondence Update on Edward White

In 2022, a book was published, Truth-Telling at Risdon Cove, which argued that the generally accepted narrative that the seminal ‘massacre’ of 20, 30, 50 or, as some even say, 100 Aboriginal people at Risdon Cove in Tasmania in 1804 was in fact false.

The authors of the book, Scott Seymour, George Brown and Roger Karge argued that the official death toll of 3 Aborigines killed, as recorded at the time and in the Historical Records of Australia was in fact correct.

A main proponent of the ‘massacre’ theory, and a death toll of 30-50, is Professor Lyndall Ryan who oversees the Colonial Massacre Map Project at the University of Newcastle. She has kindly agreed to engage in a correspondence debate on this topic, and we (the authors) present our on-going correspondence here.

To encourage debate as widely as possible, we have offered the ‘$5000 Edward White History Prize’ to the first person who can prove that our claims in our book, Truth-Telling at Risdon Cove, are incorrect.

So please join the conversation below and try to claim the prize yourself!

Posted 6 March 2023: This Post is the reply to the two emails we received from Professor Lyndall Ryan, namely Correspondence Trail #1 on 12/11/2021, and Correspondence Trail #2B on 7/10/2022.

Our responses below are thus #1A and #2C.

Starting Correspondence Trail No. 1 - [12/11/2021] - Emeritus Professor Lyndall Ryan, historian at the University of Newcastle kindly responded in late 2021 (prior to our book being published) to some questions posed by one of our contributors, Robert.

On Friday, 12 November 2021, 6:36:45 pm AEDT, Lyndall Ryan wrote:

Dear Robert

Thank you for your email and material information about the Risdon Cove massacre.

For archaeological evidence of the massacre, I would like to draw your attention to the report by Angela McGowan, ‘Archaeological Investigations at Risdon Cove Historic Site 1978-1980’, Occasional Paper No.10, Hobart: National Parks & Wildlife Service, 1985. Among other items, the paper lists a cannon ball found at the site. The paper also gives a comprehensive history of the site after it was formally abandoned in July 1804. [see Point 1 below]

Are you suggesting that Edward White did not exist? Absence of evidence about his arrival at Risdon Cove in 1803, is certainly not evidence of his absence. [see Point 2 below] .

If he did not exist, how then did he get to give evidence at the 1830 Inquiry? [see Point 3 below]

All the people who gave evidence about the massacre had known each other since 1804. [see Point 4 below]

It is unlikely that an imposter would have presented evidence. [see Point 5 below]

Yours sincerely, Lyndall Ryan. [our emphasis, and our responses to each point are below]

Our Responses #1A on 6/3/2023]

Point 1 - Archeological Evidence

On Professor Ryan’s suggestion we consulted archeologist Angela McGowan’s report, ‘Archaeological Investigations at Risdon Cove Historic Site 1978-1980’, Occasional Paper No.10, Hobart: National Parks & Wildlife Service, 1985. We also had a meeting with McGowan in Hobart to discuss her findings.

Figure 1 - Angela McGowan is an Australian archaeologist known for her work on Aboriginal and European heritage and culture in Tasmania. Photo credit: here

Figure 2 - Cover of our copy of Risdon Cove Archaeological Report by Angela McGowan

Figure 3 - Cover of our copy of Pinjarra WA Archaeological report by N Contos, et al.

We also compared the archaeology of the Risdon Cove site with that of another confirmed, so-called ‘massacre’ or ‘battle’ site, that of Pinjarra in WA in 1834, where some 20 (estimates vary from 15 to 30) Aboriginal people were killed in a clash with a government force.

Our aim in making this archaeological comparison was to see if the archaeological detritus of the Pinjarra site, a site where it is confirmed that at least 15 Aboriginal people were killed, matched that of the Risdon Cove site.

If the death toll at Risdon Cove had really been, as Professor Ryan claims 20, 30 or 50 (instead of the 3 that we claim), then one would expect that the number and type of archaeological items recovered at Risdon Cove to be at least comparable to the number of human remains and conflict detritus (muskets balls etc) that was actually found at Pinjarra.

As summarised in the table below (Figure 4), the comparison of the archaeological results for Risdon Cove with those of Pinjarra, suggests that the affray at Risdon Cove was less severe than that at Pinjarra.

Firstly, the official reports, at the time of each of the incidents, reported that 15 Aboriginal bodies were accounted for at Pinjarra, compared to just 3 at Risdon Cove. Over the intervening years at Pinjarra, some four lots of skeletal remains of six bodies, some with musket balls still lodged in the bones, were recovered. This compared to the Risdon Cove site, where no skeletal remains of Aboriginal victims have ever been found .

If the claims by the self-nominated, ‘eye-witness’ convict, Edward White were really true that, ‘there were a great many of the Natives slaughtered and wounded’ at Risdon Cove, then we would have expected that the Aboriginal skeletal remains, the musket balls and the lead-shot detritus found at Risdon Cove would have been expected to have been on a par with those recovered at Pinjarra, a known site where at least 15 people were killed.

In fact, Pinjarra had significantly greater amounts of skeletal remains and musket balls found in bones. Pinjarra was an un-settled site, whereas Risdon Cove was occupied as a settlement for a number of years after the 1804 affray, which probably explains why hunting lead-shot that was found at all.

Figures 4A,B,C,D&E - Table of comparison of the Archaeology of Pinjarra WA and Rison Cove Tasmania. Full table and links available for download here

In our opinion, based on the above archaeological comparison of the two sites and Angela McGowan’s comments, we do not believe that there was a ‘massacre’ death toll at Risdon Cove to rival that of the at least 15 killed at Pinjarra. Using this comparative methodology, we believe that the archaeological evidence for Risdon Cove does not support Edward White’s claim that, ‘there were a great many of the Natives slaughtered and wounded’

The discovery of the Cannon Ball

In her correspondence above, Professor Ryan cites as ‘archaeological evidence of the massacre’ [at Risdon Cove] the fact that a 12 pound cannon ball was found at the site’.

Figure 5A&B - The Cannon (Carronade) Ball and other small items recovered at Risdon Cove by McGowan’s archaeological dig. Source: On display at Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (TMAG) in Hobart, Tasmania.

Figure 6 - A Typical 12 pound Carronade of the times (this one ca1830 was not the one from Risdon Cove used in 1804, which has never been found, but is similar to it). Source: On display at TMAG Hobart

In our opinion, the finding of a single cannon ball is hardly evidence that a massacre occurred in which 20,30,50 or even 100 natives were ‘massacred’.

To support our opinion, we note the fact that a cannon ball was also found at the Wybalenna Aboriginal settlement in Tasmania (see Figure 7), but no one would ever claim that a ‘massacre’ occurred at Wybalenna, just because of that discovery.

It seems that dumped and/or lost cannon balls can be found on sites in Van Diemen’s Land, where Aborigines were known to have inhabited, without there necessarily having been an Aboriginal massacre on the same site.

In other words, just because a cannon ball has been found, it doesn’t necessarily mean that an Aboriginal massacre occurred.

Figure 7 - Details of the discovery of a cannon ball at Wybalenna Aboriginal settlement. Source

Point 2 - The Absence of Evidence Argument

Neither Professor Ryan nor any other historian has been able to locate any corroborating evidence that a man named Edward White was, or even could have been, at Risdon Cove on 3 May 1804.

To rely on the claim, as Professor Ryan does, that ‘absence of evidence about his arrival at Risdon Cove in 1803, is certainly not evidence of his absence’ , is a very unsatisfactory way to come to conclusions in historical research. It reminds one of that old Creationist defence used to support Intelligent Design over Evolution – ‘absence of evidence that God’s hand is at work in the evolution of life on earth is not evidence of God’s absence’ [see also the concept of Russell’s Teapot].

It is completely acceptable for people of faith to accept Intelligent Design over the scientifically proven ideas of Evolution - but that doesn’t mean the rest of us have to believe it too.

The only claim that an Edward White was at Risdon Cove in 1803 or 1804 was by the testimony of Edward White himself in 1830, when it was recorded that he testified before the Aborigines Committee and said he was an ‘eye-witness’ to the events at Risdon Cove 26 years earlier.

But what if he was lying? Remove this testimony from the ‘evidence’ and there are no other credible, corroborating facts to support that any man named Edward White was at Risdon Cove on 3 May 1804 [but see also discussion of Figure 16 below].

We believe that Professor Ryan is going a step too far in relying on the methodology that an ,’absence of evidence about an Edward White arriving at Risdon Cove in 1803, is certainly not evidence of his absence.’

Just because there is no evidence that someone was in a particular place, doesn’t mean that you can confidently write history as if he was there. Our rejoiner to this methodology would be that an, absence of evidence is not evidence of presence.

Interestingly, Australian historiography has been here before, as Professor Ryan might well recall. One of the most infamous claims of an ‘eye-witness’ not being where he said he was, is that of Lyndall Ryan’s one-time, academic supervisor, historian Manning Clark.

Like Edward White’s testimony, many historians were also convinced by Manning Clark’s ‘eye-witness’ testimony that he was in Bonn, in Nazi-Germany, on the morning after Kristallnacht in November 1938. Only that, just like Edward White, Clark’s claim was later proven to be a lie.

As writer David Marr related his story, in a SMH piece in 2007, we couldn’t help but notice the uncanny similarities between the revelations about Manning Clark and what we believe motivated our Edward White, which we have highlighted in bold in the following excerpt of Marr’s piece,

As an old man looking back on his life, Manning Clark claimed to have seen with his own eyes the horrors of Kristallnacht. Witnessing this notorious Nazi pogrom changed his life, said Clark, and made him the historian he was. It became the most famous story of a great storyteller.

"I happened to arrive at the railway station at Bonn am Rhein on the morning of Kristallnacht," he told the poet John Tranter in 1987. "That was the morning after the stormtroopers had destroyed Jewish shops, Jewish businesses and the synagogues. Burned them and so on … I saw the fruits of evil, of human evil, before me there on the streets of Bonn."

But Clark was not there that day. The historian's biographer, Mark McKenna, reveals this week in The Monthly that Clark did not reach Nazi Germany for another fortnight…It's not a small point. In the last dozen years of his life, Clark told the story on radio, on television and in newspapers…

McKenna was shaken by the discovery that Clark could not have been there that morning to see the wreckage that foretold the Holocaust. But there was no doubt about it. Working on the Clark family papers last year, McKenna found a letter Dymphna Lodewyckx had written from Bonn to Manning Clark in Oxford a couple of days after these events describing the smashed shops, the ruined synagogue and a rabbi's house in flames: "The violence was over when I came - but the crowds were everywhere - following the smiling SS men, children shouting in excitement, grown-ups silent …"

At first McKenna thought he had made a mistake. "Like many others, I had taken Clark at his word. I had even quoted the Kristallnacht story in my published work. I reread Dymphna's letter carefully, checked Clark's diary entries, and saw that it was impossible for Clark to have been in Bonn on the morning of 10 November. As his own diary confirms, he did not arrive in Bonn until 26 November."…

Presenting his Kristallnacht discovery for the first time to an academic conference last year, McKenna had no doubt the historian set out to deceive. "I am convinced that Clark chose deliberately to place himself on the streets of Bonn, knowing full well that he was not there.

This was Clark's inner lie. But he had also told the story in public, and traded on his audience's trust in him as a historian." McKenna asked: "Does this make Clark a fraud?" His answer then was yes and no: while inventing the details of that morning said a great deal about Clark's self-dramatising character, McKenna didn't doubt for a moment that what Clark learnt of the pogrom and what he saw of its aftermath a few weeks later had the profound impact he always claimed.

McKenna writes: "In this sense, there is no fabrication."…But in a chunk of the biography published this week in The Monthly, McKenna has taken a big step back from his original allegation of deliberate deceit. "I believe that the older Manning Clark did possess some awareness of the fact that he was not present on the morning after Kristallnacht," he writes. "But to claim to know the extent to which he was conscious of it is to claim to know the inner depths of his mind." The fallible memory of an old man must not be ruled out, argues McKenna. "I know I can never recover what he truly remembered, the memory of his inner voice, the voice only he heard."

The historian's son, The Australian Financial Review journalist Andrew Clark, has told the Herald, "Mr McKenna has discovered what he believes is a discrepancy in the dates of my father's visit to Bonn … He is not contesting that my father visited my mother in Bonn after Kristallnacht, just the precise date of his arrival." He argued that the fact his father was recalling events 40 or 50 years in the past "goes some way in explaining any alleged discrepancy in dates".

Clark faults McKenna for not providing readers with a full context of those events. "If he had done so, readers would have known that at the alleged time of my father's arrival in Bonn, the Nazis' murderous acts against Jews was still in evidence."… "He created himself as a myth, cultivating a theatrical persona of the people's priest and sage, telling history as parable. And as the Kristallnacht epiphany reveals, the moral of the parable always mattered more than the facts."

One wonders in fact, if many historians and commentators of today know, deep down in their inner thoughts, that Edward White’s testimony is ‘dodgy’; and professionally they should not really be relying upon Edward White and his testimony at all when they study the events of Risdon Cove. However, the parable of the ‘genocide’ of the Tasmanian Aborigines, needing to be shown to have started from the get-go of colonisation on 3 May 1804 at Risdon Cove, is what ‘always mattered more than the facts’ and so they self-censure, and say nothing against this new historical ‘orthodoxy.’

Point 3 - Professor Ryan asks us, “If he [Edward White] did not exist, how then did he get to give evidence at the 1830 Inquiry?

Our response is that we are not denying that an Edward White did exist. We agree that a man calling himself Edward White did give ‘evidence at the 1830 inquiry.’

What we are saying however, is that this 1830 man was not present at Risdon Cove on 3 May 1804. He existed in Hobart and Risdon Cove in 1830, but he did not exist in Hobart or Risdon Cove in 1804.

In fact, we believe that we have presented enough evidence in our book, Truth-Telling at Risdon Cove, to show that no-one called Edward White was present in early Hobart Town or Risdon Cove in the years 1803 or 1804.

Point 4 - Professor Ryan states that, “All the people who gave evidence about the massacre had known each other since 1804’.

In our opinion, there is not a lot of documentary evidence to support Professor Ryan’s claim that, “all the people who gave evidence … had known each other since 1804.”

The five men who gave evidence at the 1830 Aborigines Committee, regarding the affray at Risdon Cove, were two former convicts, Edward White and Mr W T Stocker, the Reverend Robert Knopwood, Mr Kelly [believed to be the Hobart habour-master James Kelly who was a 12-year old boy in 1804], and Robert Evans, a former marine Sergeant.

Of these five, only Edward White claimed to be in Risdon Cove on the day of the affray, 3 May 1804, and only he claimed to be an ‘eye-witness’ to the events. The other four were all in Hobart Town on that day and so could not vouch for White’s claims, and were not on-site, to ‘eye-witnesses’ to the events themselves.

It is easy to find independent, documentary evidence that four of these witness were contemporaries in Hobart in 1804.

For example, Rev Knopwood, Robert Evans and William Thomas (W.T) Stocker are listed on the 1804 First Settlers Association of Hobart list (here). Although we haven’t been able to find any documentary evidence that James Kelly was in Hobart in 1804 (he would have been a 12 year old boy at the time), there are records of him being an apprentice sealer from January 1804 to 1807 in Bass Strait, so it is quite possible he was in Hobart in May 1804. James Kelly afterwards spend most of his life in Van Diemen’s Land, principally in Hobart (See Figure 8).

Figure 8 - James Kelly and his family tomb in St David’s Park Hobart, showing the link of the Kelly family to Van Diemen’s Land

Thus, Professor Ryan would appear to be justified to claim that these four men probably ‘had known each other since 1804’.

But the fifth man, Edward White is the odd one out. We were unable to find any evidence linking him to these four men in 1804. Indeed, the first documentary evidence for any convict by the name of Edward White appearing in Van Diemen’s Land was on the Hobart muster of 1811.

We provided evidence in our book, Truth-Telling at Risdon Cove, that this 1811 Edward White was in fact a convict who was convicted in Ireland in 1804 and was transported to Port Jackson on the Tellicherry in 1806, two years after the Risdon Cove affray in 1804. We also provided evidence that shows that this 1811 Edward White was also the same Edward White who testified before the Aborigines Committee in 1830.

Thus, like Manning Clark and his Kristallnacht claim, the 1830 Edward White could not have seen that, ‘there were a great many of the Natives slaughtered and wounded’ at Risdon Cove on 3 May 1804, because he could not have been there at the time. He was still in Ireland.

In two publications, Professor Ryan attempts to further link together these five witnesses from the 1830 Aborigines Committee. We believe however, that her attempts are misleading.

In the first publication, from her 2004 paper, Risdon Cove and the Massacre of 3 May 1804: Their place in Tasmanian History, Professor Ryan tells us on page 115 that ‘Knopwood and White’ ‘toured the Risdon Cove site’,

Figure 9 - Excerpt from page 115 of Professor Ryan’s 2004 seminal paper on the Risdon Cove ‘massacre’, Risdon Cove and the Massacre of 3 May 1804: Their place in Tasmanian History.

This leads the reader to assume that the Reverend Robert Knopwood, one of the witnesses at the 1830 Aborigines Committee is touring the Risdon Cove site with another of the five witnesses, namely Edward White, who Professor Ryan just refers to as ‘White.’ This lends some credence to Professor Ryan’s response to us that, “all the people who gave evidence about the massacre had known each other since 1804.”

But is this true? Did Reverend Knopwood tour the Risdon site with Edward White?

As her source, Professor Ryan provides, in footnote #33, a citation to Rev. Robert Knopwood’s diary (Figure 10).

Figure 10 - The Footnote #33 citation refers to Knopwood’s diary [note in our copy, the footnote number “33” has been truncated during the copying process to just a “3”]

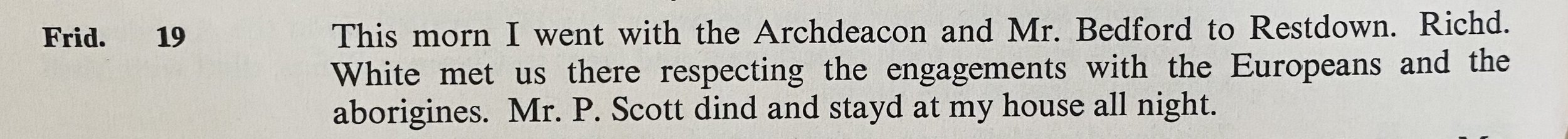

However, when we refer to Knopwood’s diary of 19 March 1830, we find that Knopwood says he met a Richard White there, not Edward:

Figure 10 - Excerpt from a transcription of Knopwood’s diary of 19 March 1830. Source: The Diary of the Reverend Robert Knopwood 1803–1838, Mary Nicholls (ed), Tasmanian Historical Research Association, 1977

Now maybe Knopwood made an error - maybe he did meet Edward White at Restdown [alternative name for Risdon Cove] on 19 March 1830, but he then mistakenly recorded his name as Richard when he came to write up his diary later that day, or in the next morning. In his testimony three days earlier, on 16 March 1830, Edward White did say, “I could show all the ground”, when questioned about the Risdon Cove site and the relative placement of the soldiers and the natives. Perhaps this offer of Edward White’s, ‘to show all the ground’, was taken up by the Committee and they visited Risdon Cove (Restdown) with Edward White.

But maybe they didn’t. Maybe it really was in the presence of a Richard White, whoever that may have been. Perhaps Richard White was a caretaker there or an employee of the current owner of the Restdown (Risdon Cove) farm. We have found the name Richard White in the records of the time, but we have been unable to link that name to Restdown or Risdon Cove.

But the important point is that Professor Ryan should have included this christian name discrepancy in her citation. Professionally, if she thought Knopwood made an error, she should have noted it as such in her citation. To just omit the ‘Richd’ and refer to him only as ‘White’ leads her readers to naturally assume it was our Edward White, the witness at the 1830 Committee. This is misleading.

In a second publication, her 2012 book, The Tasmanian Aborigines, Professor Ryan again attempts to further link the five witnesses to the actual ‘massacre’ site, and to each other, when she writes:

Figure 11 - Excerpt of page 51 from Lyndall Ryans, Tasmanian Aborigines, Allen & Unwin, 2012.

In our opinion, this text is misleading to Professor Ryan’s readers as it implies a much closer association between the five witnesses themselves, and with the site at Risdon Cove, than the evidence would seem to justify.

For example, firstly, Professor Ryan claims that the marine Sergeant Robert Evans, ‘visited the site of devastation shortly after’. We could find no evidence, either in Evans’s testimony nor in any other documentary source during our research, to suggest that this visit occurred. Instead, Evans told the Committee that he had just ‘heard’ of the events - that is, he was relying on hearsay and not a personal experience from having ‘visited the site’. His recorded testimony to the 1830 Aborigines Committee is in Figure 12.

Figure 12 - Testimony of marine Sergeant Robert Evans, as given to the 1830 Aborigines Committee. Source: Report of the Aborigines Committee, published in British Parliamentary Papers, Colonies – Australia, Volume 4, Irish University Press Series, 1970

Secondly, Professor Ryan claims that, 'a week later [after the so-called ‘massacre’] the youths, James Kelly and John Pascoe Fawkner, along with Robert Knopwood, rowed across the river from Hobart to the site.’

To our mind this appears to be a ‘fabrication’ by Professor Ryan. In our opinion, this ‘boat excursion’ appears to have been created by Professor Ryan to link Knopwood with both James Kelly, who would have been about 12-years-old at the time, and the future diarist, John Pascoe Fawkner, who published his memoirs in 1869, which included comments on the Risdon Cove affray.

We have searched far and wide trying find any documentary evidence to suggest that the Right Reverend Robert Knopwood in 1804 actually scooped up two 12-year-old boys from Hobart Town, popped them into a rowboat, and then rowed across the Derwent to visit Risdon Cove - but we could find nothing, there no record of this at all.

We then wondered why on earth would Knopwood select these two particular boys - one an apprentice sealer and the other the son of the still shackled convict, John Fawkner, for this day-trip?

It just does not seem to make sense. Unless of course, Professor Ryan was simply ‘setting up’ this boat excursion scenario because she knows that twenty-six years later, Knopwood and Kelly will be witnesses at the 1830 Aborigines Committee, and sixty-two years later in 1866, John Pascoe Fawkner will start to write a memoir, ‘Reminiscences of Early Hobart Town. 1804-1810’, covering his early life in Hobart Town in which he provides a version of the Risdon Cove ‘massacre.’

This ‘boat excursion’ thus creates an association between all these three men in 1804 at the time of the ‘massacre’ to show, as Professor Ryan then claims, that they ‘had known each other since 1804’.

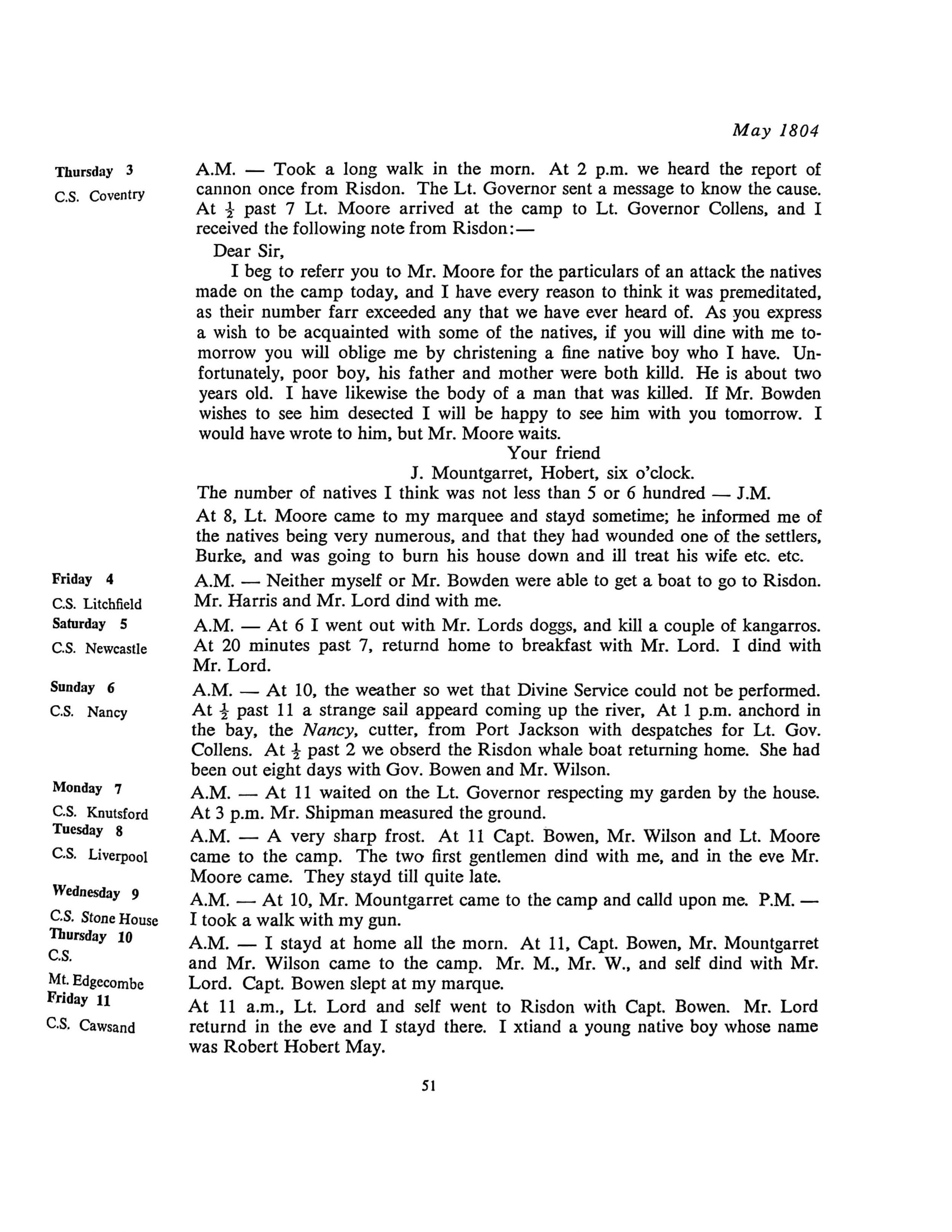

It is a nice try by Professor Ryan but, in our opinion, it is simply not true - there is no evidence that we could find, and Professor Ryan herself offers no citation either, that Knopwood rowed these two boys across to Risdon Cove as the Professor claims. Knopwood, who was a committed and detailed diarist, only noted that he, a Mr (Lt.) Lord and Capt. Bowen crossed to Risdon Cove on Friday 11 May 1804, a week after the affray. He stayed the night there and christened [xtiand] the orphaned Aboriginal boy, Robert Hobart May (see Figure 13 for Knopwood’s diary entries of 3 to 11 May 1804).

There is no mention in Knopwood’s diary entry of the two boys, Kelly and Fawkner, accompaying him. There is no mention of any Aboriginal bodies from the massacre, nor any mention of any burials. If there was a mountain of some 20, 30, 50 or even 100 bodies, or a field of gravesites, or a funeral pyre, then an observant and curious daily diarist such as Knopwood would most certainly be expected to have made a record of it.

But he didn’t, because none of this happened - no boys on a boat excursion and no massacre.

Figure 13 - Excerpt from Rev Robert Knopwood’s diary 3 to 11 May 1804. Source: The Diary of the Reverend Robert Knopwood 1803–1838, Mary Nicholls (ed), Tasmanian Historical Research Association, 1977

In our opinion, we also believe that it is misleading of Professor Ryan to attempt to link John Pascoe Fawkner to some of the other five witnesses to the 1830 Aborigines Committee. Fawkner was not a witness to the Committee, but he did leave a record of a version of the Risdon Cove ‘massacre’ in his later life, when he wrote his memoir in 1866.

It appears to us that Professor Ryan may be trying to lend credence to Fawkner’s version of the Risdon Cove events by firstly claiming that he was a 12-year-old contemporary to the witnesses, Knopwood and Kelly during their ‘boat excursion’ to Risdon Cove, and secondly by including Fawkner’s version of the ‘massacre’ in her passage above (Figure 11). By quoting Fawkner’s version along with the others, Professor Ryan leads the reader to believe that his testimony was also given to the 1830 Inquiry along with the others, despite her use of the qualifier ‘later’.

The reality is that John Pascoe Fawkner’s version of the events is wholly unreliable and based on hearsay, and was written very much later, indeed some sixty-two years later after the event !

Other historians take the claims of John Pascoe Fawkner with a grain of salt. For example, in an Introduction to an edition of Fawkner’s memoir, Reminiscences of Early Hobart Town, 1804–1810, (The Banks Society, 2007), the historian John Currey writes that,

‘As a preliminary to setting down his reminiscences Fawkner made several visits to Tasmania to refresh his memory and to talk to the aged survivors of Hobart’s early days’. (ibid., p11)

Currey then concludes that,

‘Despite his zeal for veracity, Fawkner’s account contains some glaring and significant mistakes, the result, probably, of accepting without question the history preserved among the surving settlers of early Hobart Town.’ (ibid., p11-12)

In our opinion, the reasons why Professor Ryan should not rely on John Pascoe Fawkner’s account of what happened at Risdon Cove on 3 May 1804 is because there is no third party corroboration to support Fawkner’s claims, and his account was based, as he admits, on hearsay.

Fawkner was a 12-year-old boy in Hobart at the time of the Risdon Cove ‘massacre’ and he started to write his reminiscences some sixty-two years later in 1866, when he was 74-years-old and three years away from his own death.

An excerpt of his account, in Figures 14A&B below, includes what Currey and many other historians see as, ‘significant mistakes.’

Figures 14A&B - Excerpts from John Pascoe Fawkner’s, Reminiscences of Early Hobart Town, 1804–1810, The Banks Society, 2007, p23-24 describing his version of the Risdon Cove affray (‘massacre’)

There are several obvious and ‘significant mistakes’ in Fawkner’s account.

For example, Lieutenant Bowen was not present at Risdon Cove on that day. All historians know from corroborating evidence that Bowen was away on an excursion. The camp commandant on 3 May 1804 was Bowen’s second-in-command, Lieutenant William Moore, who directed the operations during the clash between the settlers and soldiers, and the Aborigines. Fawkner could not even get such a basic fact correct.

Additionaly, there is no evidence in the records, or in other privately written accounts, to corroborate Fawkner’s claims such as: that the Aborigines were ‘engaged in dancing’; that both the carronades (cannon) on site were fired’ (only one shot was recorded as being heard); that they were loaded with ‘pieces of iron and broken bottles’; and that ‘about thirty bodies were found and burnt or buried’ to ‘clear the air of effluvia.’

In our opinion, it is unjustified for Professor Ryan to give such a prominent place in her account of the Risdon Cove affray to such an unreliable informant as John Pascoe Fawkner.

The Edward White References

An interesting question arises in Professor Ryan’s claim that, “All the people who gave evidence about the massacre had known each other since 1804.” This begs the question, why then didn’t Edward White use any, or all of, these people (the five witnesses to the Aborigines Committee) as references to support his petitions to the government for a pension, petitions he lodged straight after the hearings concluded?

If White was so well known to all five, why did they not vouch for him, especially the Reverand Knopwood, a most reputable reference one would have thought?

Our opinion, as presented in our book, Truth-Telling at Risdon Cove, is because we believe that people in Hobart Town knew that ‘Old Edward White’ was a local gossip, an ex-con liar and scammer and most probably did not arrive at Risdon Cove with the first settlement as he claimed. We now speculate that many in Hobart Town knew he was just a run-of-the-mill convict who had been transferred from Sydney for a further punishment just prior to the Hobart muster of 1811.

Figure 15 - An 1836 Hobart article referring to ‘Old Edward White’. Source: Colonial Times 29 Nov 1836

Perhaps the likes of respectable people such as the Reverend Knopwood, harbour-master James Kelly and ex-marine Sergeant Richard Evans were not willing to vouch for the character of the ex-convict, ‘Old Edward White.’

In the end however, Edward White was able to secure a mix of references, including that of fellow ex-convict, John Fawkner senior, who was John Pascoe Fawkner’s father.

Our claim that Edward White was lying about his presence in Risdon Cove and Hobart in 1804 has been allegedly been challenged by historian Phillip Tardif (see the commentary here regarding his forthcoming critique of our work in THRA’s April issue).

Tardif is said to have written in his THRA article that,

‘… the clear statement by long-term Hobart resident John Fawkner that he had known White for almost thirty years (i.e. since 1804), make for a strong case in his [White’s] favour.'

Yes, we do agree that of all the character references obtained by Edward White, this one by John Fawkner senior, dated May 27 1833 (Figure 16), comes the closest to corroborating Edward White’s claim that he was in Risdon Cove or Hobart in 1804, thus suggesting that, in terms of timing, he could have been an ‘eye-witness.’

Figure 16 - Character reference by ex-convict John Fawkner senior for Edward White (the petitioner) stating that he has known White ‘…for many years, nearly thirty…’. As this reference was dated May 27 1833, ‘nearly thirty’ puts their acquaintance back to ‘nearly 1803’ which would appear to cover ‘since 1804’, the year of the Risdon Cove affray. Source: Tas Archives, CSO1/655/1 File 14693, p112; Microfilm Z1905

But this reference still raises some questions. As we argue in our book, Truth-Telling at Risdon Cove, ‘nearly thirty’ years could easily mean anything from say, 26 years (1806) to 29 years (1804). In our own lives, when are asked when did we meet a particular person in the past, we rarely know the exact date or year. We could easily reply, ‘nearly thirty’ years ago for someone we remember meeting in the 1990s. We don’t recall the exact year - it could have been 1993, exactly thirty years ago, but then it may have been say, 1997, twenty-six years ago. Much easier to simply say, ‘nearly thirty years ago’ so as to encompass all of the 1990s, as we are sure it was some time then.

Another character reference provided for Edward White was by William Beaumont, who wrote:

I have known the petitioner Edward White above twenty years, and have always considered him to be a man of good character.

Wm Beamont , 27 May 1833 [Source file: Tas Archives, CSO1/655/1 File 14693, p112; Microfilm Z1905]

Beaumont probably uses the term, ‘above twenty years’, that is, sometime before 1813, because he too cannot remember the exact year. Was it 1804 as claimed by White (29 years ago,) or 1806 to 1811 (22 to 26 years ago) as we claim in our book? All of these are ‘above twenty years.’

There are two critical points with regard to the veracity of John Fawkner seniors ‘nearly thirty’ years reference.

Firstly, if it was true that Edward White was in the Risdon Cove or Hobart area in 1804 and knew John Fawkner senior at that time, then why is it that John Fawkner (Faulkner) the convict, and all his family (wife Sarah Faulkner (Fawkner) and children, Elizabeth and John) are listed on the First Settlers Association of Hobart List 1804, but Edward White is not? The records of the First Settlers Association are generally considered a complete list of all residents at that time in Hobart (and Risdon Cove) - John Fawkner and all his family are on the list, but not his friend Edward White. Why not?

As far as we aware, historians such as Professor Ryan and Phillip Tardif have not provided any reason to explain this significant discrepancy to Edward White’s story.

One reason for the discrepancy is because Edward White was lying - he wasn’t there in 1804. We believe that John Fawkner senior probably did first met White ‘nearly thirty’ years ago, but it was sometime in the period 1808 to 1811 (22 to 25 years ago).

Secondly, if it was true that John Fawkner senior, who was still a convict in 1804, knew Edward White, (who also was a convict at that time, if he was in fact even there), then presumably John Fawkner junior (he changed his name to John Pascoe Fawkner later in life) would have met, or at least known of, Edward White in early Hobart Town.

Hobart in 1804 was a small, penal settlement and one would have thought that most people knew, or knew of, most of the other inhabitants.

Additionally, Professor Ryan claims a young 12-year-old John Fawkner junior was taken for a boat visit to Risdon Cove in 1804 by the Reverend Knopwood. Presumably Knopwood would have obtained permission from young John’s parents? Presumably a young John would have rememebered this unusual boat excursion with Knopwood and the other 12-year-old boy James Kelly?

It is therefore very confusing to us as to why, when young John Fawkner grew up and published his reminiscences, as the 74-year-old John Pascoe Fawkner, he made no mention of either his father’s old friend Edward White, the key ‘eye-witness’ to the events at Risdon Cove, nor does he recall his supposed boat excursion to Risdon Cove with the Reverend Knopwood and the other boy, James Kelly.

Instead, John Pascoe Fawkner presents a unique and befuddled version of the affray at Risdon Cove, which no other historian has been able to corroborate with firm evidence.

This leads us to our speculation that the reference by John Fawkner senior, as to his knowledge of Edward White for ‘nearly thirty’ years, should not be taken as being anything more than one ex-con giving a reference to another ex-con. Edward White’s petitions all stressed the fact that he was one of the original inhabitants of Hobart - a long time, loyal resident - and therefore was entitled to a pension from Governor Arthur. Edward White needed friends to vouch for his long-time residency, even if it wasn’t true. John Fawkner senior provided that, couched in terms that were imprecise enough - ‘nearly thirty’ - so as to avoid censure if it was found out to be wrong, but close enough to keep his friend happy and support White’s claim that he was a long-time resident of Hobart.

We do not believe that John Fawkner’s reference is precise enough, nor credible enough, to place Edward White at Risdon Cove on 3 May 1804. Perhaps Governor Arthur also thought the same - he refused all of White’s petitions and did not reward him with anything based on White’s claims that he was an original resident of Hobart Town.

Point 5 below - “It is unlikely that an imposter would have presented evidence” [Prof. Ryan]

We are not saying that the Edward White who testified before the 1830 Aborigines Committee was an “imposter” - he really was an ex-convict whose name was Edward White.

But what we are saying is that he was lying. He only arrived in New South Wales in 1806 and then turned up in the Van Diemen’s Land records in the Hobart muster of 1811. He then lived in Van Diemen’s Land until he died, we believe, in 1841.

In 1830 he appeared before the Aborigines Committee and provided testimony, which we claim was a fabrication, based on the hearsay about the Risdon Cove affray that he had picked up over the many years he had lived in and around Hobart.

In our book, Truth-Telling at Risdon Cove, we provided the evidence regarding his many unsuccessful petitions to get a pension from the government in the years just after he gave evidence to the Committee, as he claimed, ‘to his most clear recollection.’

We claim, based on the evidence of his petitions, that the 1830 Edward White indeed had sufficient motive to lie to the Committee, and it was not ‘unlikely’ at all for a person of White’s character to do so. He was not an imposter but a liar.

Correspondence Trail No. 2 - [5/10/2022] - Roger Karge (co-author of Truth-Telling at Risdon Cove) submitted an on-line comment at the University of Newcastle Massacre Map:

Roger Karge Wrote:

We believe our original research confirms that the convict & ‘witness’ Edward White was lying about the events he says he saw on the day of the massacre on May 3, 1804. We believe that we have proven that he was not even in the colony at that time - he arrived in 1806 - so he could not have been a ‘witness’ to the events.

Thus the only two eye-witnesses to the event, who reported ‘3 natives killed and an unknown number wounded’ and ‘a small boy orphaned’ are the only historically contemporary and reliable sources.

Thus, we believe that, based on the definition of a massacre being ‘at least 6 killed’, this Risdon Cove event is no longer a true massacre but rather an affray or clash.

You do refer to our research in your Risdon Cove entry (the newspaper reference) and we urge you to study our research in detail. I will send you an August 2022 review by THRA of our book via your email address

2B Response from Prof. Lyndall Ryan [7/10/2022]

Dear Roger Karge, Thank you for your email.

I have a copy of your book and the review published in THRA.

Alas, I do not agree with your interpretation of White, which entirely depends on when he arrived in Tasmania. Your reliance on the shipping lists does not prove that he was not at Risdon Cove on the day of the massacre.

As you have found in your own research, convict records were imperfect at least until the mid-1820s. And even then, the names of some convicts slipped through the bureaucratic net.

It is possible that a record relating to Edward White was lost when Governor Collins’ papers were burnt upon his death, and other information may have been included in the missing 3 years of the diary of the Rev. Robert Knopwood.

We do know, however, that White sought the support of long term well known settlers when he requested financial help from Governor Arthur in the 1830s. I was surprised that you simply dismissed these men, who clearly knew White well and readily supported his request.

The conspiracy theory approach to history rarely achieves the desired outcome. Suggesting that White attended the Aborigines Committee before he gave his testimony, is pure fantasy.

Yours sincerely, Lyndall Ryan

Our Reply #2C Reply by Roger Karge [9/3/2023]

Dear Professor Ryan,

Thankyou for your prompt response.

I believe that the critical point here is that we have, in our bookTruth-Telling at Risdon Cove, provided enough documentary evidence to show that the 1830 ex-convict Edward White, testifying at the Aborigines Committee, was one-in-the-same convict Edward White who arrived in Sydney in 1806 on the Tellicherry. This Tellicherry Edward White could not have been at Risdon Cove in 1804.

You state that, “alas, I do not agree with your interpretation of White, which entirely depends on when he arrived in Tasmania”, - but isn’t that exactly point? If the testifying Edward White of 1830 is identified as arriving in the colony after 3 May 1804, he then could not possibly have been an ‘eye-witness’ to the events at Risdon Cove? In our opinion, the veracity of his claims very much depends on when he arrived in Tasmania.

You also state that, “And even then, the names of some convicts slipped through the bureaucratic net”. Are you able to provide evidence or examples of convicts to support this assertion?

Are you resting your historiography on a claim that a convict named Edward White ‘slipped through the bureaucratic net’? - that is, he was transported to the colony on a ship, which we do not know the name of, on a muster or indent list that has been lost or destroyed, who was not recorded on the comprehensive Hobart Town First Settlers association lists of either 1803 and 1804 and who then magically appears in the records of 1830 to give his eye-witness account to the Aborigines Committee?

Yes, we have relied upon shipping and muster lists to determine when this 1830 Edward White, and all the other convicts named Edward White, arrived in Australia. And none of them arrived alive early enough to get to Hobart by 1803 or 1804.

If your agrument relies on the fact that we may have missed another convict by the name of Edward White, you need to provide evidence of when and how he got to Hobart by 1804. You also need to explain how your ‘yet to be found 1804 Edward White’ was able to replace our 1830 Edward White, who we show was off the 1806 Tellicherry. It was our 1806 Tellicherry Edward White who testified at the 1830 Aborigines Committee - we believe our evidence shows this linkage.

We believe we have searched all the muster/indent lists for all the convict transports between 1788 and 1830 as listed in Charles Bateson’s, The Convict Ships, 1787–1868, (Brown, Son & Ferguson, 2014). If you think Bateson omitted a convict transport ship from his list, please advise us and we will attempt to track it down and locate the convict manifests/indents for that ship to see if they contain a convict named Edward White.

Even if some convict documents have been lost or destoyed prior to 1820, as undoubtably they have, it should not affect our research as we (along with many other researchers) have identified all the convict transport ships on Batesons comprehensive list and we have located all the Edward Whites on the musters/indents for those ships up until 1830. Thus, we believe we have collated and accounted for all the Edward Whites who arrived in Australia, even if subsequently their individual convict records were lost or destroyed. None of those Edward Whites on our list arrived and survived early enough to be in Risdon Cove by 1804. Additionally, the only Edward White that fits the description, and could be placed in Hobart by 1830 so as to testify, was our Edward White off the 1806 Tellicherry.

We have addressed the friends of Edward White in our commentary above. In our opinion, none of them provided enough detailed and dated information to prove that the 1830 Edward White was at Risdon Cove in 1804. Recommendations such as ‘nearly thirty’ years, or ‘above twenty years’ are far too vague for the question at hand here - did White’s friends know he was at Risdon Cove on exactly 3 May 1804? None of them ever gave a recommendation accurate enough to claim this as fact.

In our opinion, a Russell’s Teapot approach to historography - an absence of evidence is not evidence of absence - is a very unsatisfactory, and could be thought of as borderline denialism.

Based on the research we have presented, we believe it is time for the history profession to reconsider the events that occurred at Risdon Cove on 3 May 1804.

Rather than the current orthodox view, where Edward White’s testimony has pride of place amongst senior historians (See Tardif, Ryan, Reynolds, et al) we believe these senior historians, yourself included, should appreciate that absence of evidence is not evidence of presence.

The really critical point is that there is only one source of the claim that the 1830 Edward White was an eye-witness to the events at Risdon Cove on 3 May 1804, and that is Edward White himself. Today’s orthodox historians should put on the cap of the scientific method and ask themselves - “What if the 1830 Edward White was lying?” and “My orthodox theory says he was speaking the truth, so what research do I need to do to prove my theory wrong?”

This is the ‘scientific method’ that we have applied in our book,Truth-Telling at Risdon Cove, and we believe we proven, relatively scientifically using the data and evidence available in the existing records, that the ‘orthodox’ view wrong. Edward White was lying and he wasn’t at Risdon Cove on 3 May 1804.

Hence our call for a reconsideration of the events at Risdon Cove on 3 May 1804, which we hope you will initiate.