Was Lisa Jackson Pulver's Grandmother Aboriginal and Born under a Tree? - Part 6

In Part 5 of the Story of Lisa Jackson Pulver, we began the genealogical research into the maternal branches of Professor Lisa Jackson Pulver’s family.

In Part 5, it was shown that the records provided no evidence at all that the Professor’s maternal ancestors, the Smiths (via her Scottish grandfather), the Smidts (via her great-grandfather) or the Powells (via her great-grandmother) had any Aboriginal ancestry. All the ancestors of these families were from England or Ireland (See Figure 1).

In this post number 6 we will provide further evidence to show that the Cowper family from a branch on Professor Lisa Jackson Pulver’s maternal family tree were also not Aboriginal. Instead, the records show that they were of English descent and in fact, the Cowper family played a significant part in the story of the Colony of New South Wales.

Highlighted in yellow in Figure 1 are the Cowper family ancestors of Professor Jackson Pulver’s supposedly ‘Aboriginal’ grandmother, Clarice Mary Powell, who is highlighted in orange.

Figure 1 - Professor Lisa Jackson’s maternal grandmother, Clarice Mary Powell (highlighted in orange) is claimed by the Professor to be Aboriginal. Clarice’s father [Clarence J.A. Smidt] is not Aboriginal, but instead is of English and Irish descent. Clarice’s grandfather [Edward Richard Powell] is not Aboriginal - all his family are of English or Irish descent. Clarice’s mother [Ada Beatrice Powell] and her grandmother [Mary Eliza Matilda Cowper] are not Aboriginal via the Cowper family patriarch, Thomas Cowper, who was born in England (all highlighted in yellow). Sources: public records. File download here

Professor Jackson Pulver claims that her maternal grandmother, Clarice Mary Powell, was Aboriginal and that is how she inherits her Aboriginality.

In an interview on the 25th of February 2013[4] at the University of New South Wales, the Professor told her interviewer that,

‘… My mother was born a Smith and her mum was born up on the far north coast of New South Wales in an island in the mighty Clarence River and she fled to come down to Sydney and lived in Sydney as a Maori for a while and then, yes, eventually got back with her family and identified who she was. So that’s my mum’s side…

Similarly, in an interview with the Sydney Morning Herald on 8 March 2017, we learn that,

‘… Jackson Pulver never knew her grandfather and was brought up to say her grandmother was a "Maori princess", but both her maternal grandparents were Aboriginal.

She says her grandmother was paranoid. "We weren't allowed to take gifts from people, because they would be laced with poison. That was her family history coming out, because they were poisoning Aboriginal people when she was a wee kid…’

And in another interview, Professor Jackson Pulver told us that her grandmother,

‘…was born third tree from the left on a small island in the beautiful Clarence River, on the Northern New South Wales Coast.’ (listen here from 04:40)

Is what the Professor is telling us here in fact true, or is she mistaken in her beliefs?

The Cowper Family

Another diagram of the Cowper family branch of the maternal family tree for Professor Jackson Pulver has been prepared below in Figure 2.

Using the publicly available genealogical records, we have extended this branch right up to the Reverend William Cowper, who was invited to the Colony of New South Wales in 1809 as a chaplain by one of the colony’s earlier chaplains and magistrates, the infamous Samuel Marsden.

Figure 2 - The Cowper family branch of Professor Lisa Jackson Pulver’s maternal family tree. We have excluded from this branch, William Macquarie Cowper, who was the half brother of Thomas Cowper, and who was the dean and archdeacon of Sydney in the late 1800s [See Further Reading below] (Sources: public records)

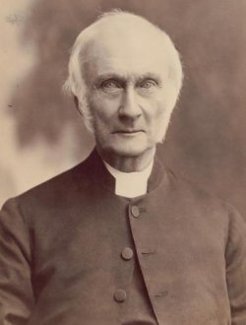

Figure 3 - Rev William Cowper (1778-1858), father of Thomas Cowper.

Rev. William Cowper was the third Chaplain to the colony of New South Wales. He was appointed to St Philip’s, Sydney in 1809 and served in that parish until his death in 1858. He was the 4X great-grandfather of Professor Jackson Pulver. Source: State Library of NSW

Rev. Cowper was Professor Jackson Pulver’s 4X great-grandfather. He migrated to the colony with his second-wife and three sons from his first marriage.

One of those sons was Charles Cowper, who went onto become Premier of NSW and was knighted as Sir Charles Cowper. He was thus the Professor’s 3X great-granduncle.

Figure 4 - Sir Charles Cowper KCMG (1807 - 1875), 2nd Premier of New South Wales (26 Aug 1856 – 2 Oct 1856). Brother of Thomas Cowper and son of Rev. William Cowper, and thus Professor Lisa Jackson Pulver’s 3X great-granduncle. Source: ADB

One of the other sons of Rev. William Cowper was Thomas Cowper, the Professor’s 3X great-grandfather of whom she is a direct descendant.

The Professor thus expects us to believe, without offering any independent evidence, that her grandmother was the Aboriginal great-granddaughter of Thomas Cowper and the 2X great-granddaughter of the Reverend William Cowper (later an Archdeacon).

Figure 5 - Purported to be an image of Thomas Cowper, Professor Jackson Pulver’s 3X great-grandfather. The Professor claims that his great-granddaughter was Aboriginal. Source: Ancestry.com user vgowans_1 originally shared this on 10 Oct 2009

Figure 6 - Purported to be a photograph of Thomas Cowper, Professor Jackson Pulver’s 3X great-grandfather. The Professor claims that his great-granddaughter was Aboriginal. Source:Ancestry.com user gasman35 originally shared this on 03 Jul 2015

The Cowper family were very prominent in the life of the early nineteenth century colony of NSW and many historical records survive which detail various aspects of their lives. However, we could find no record that mentions that one or more members of the family were Aboriginal.

Instead, records exist that indicate that the Cowpers were specifically not Aboriginal. For example, the records show that one of the duties of Rev. William Cowper was to administer to the needs of the Aborigines. The records don’t talk about Rev. Cowper administering to the needs of his people.

During our research his name appeared in such places as being on the 1815 committee (Figure 8) that oversaw Governor Macquarie’s attempt to establish the, ‘Black Native Institution’, at Parramatta in 1815 (Figure 7).

The full Rules & Regulations are an interesting read and can be viewed online here.

A short history of the Black Native Institution is here.

Figure 7 - Front page of the Rules & Regulations of the 1815 Black Natives Institution in Parramatta. Professor Jackson Pulver’s ancestor, Rev. William Cowper was on the Committee that developed these Rules & Regulations. Source: State Library of NSW

Figure 8 - Professor Jackson Pulver’s ancestor, Rev. William Cowper was on the Committee that developed the Black Native Institution Rules & Regulations. Source: State Library of NSW

Another place where the name of Rev. William Cowper was recorded was in relation to the, “Mission to the Aborigines. Report of the Aboriginal Mission, at Wellington Valley, for the year 1836 : Compiled from the Statements of the Rev. W. Watson”, which was mailed as a letter by Rev. William Cowper, Sydney, to Danderson Coates, Secretary of the CMS in London, the last side with address panel addressed in Cowper’s own hand, ‘D. Coates, Esq., Church Mission House, Salisbury Square, London’.

This item is on sale for $12,000 at the antiquarian book-seller Douglas Stewart in Melbourne (as of Dec 2022).

Figure 9 - Letter concerning ‘Mission to the Aborigines’. Mailed as a letter by Rev. William Cowper, 1836

Source: Douglas Stewart in Melbourne (as of Dec 2022)

The report makes for interesting reading and mentions the problems encountered at the mission such as,

‘… a deplorable intimacy existing on all hands, between European men and Aboriginal females…’ which the misionaries were trying to overcome…’

Another interesting comment shows that ‘humbugging’ was even a problem in the early days for those Aborigines who wished to enter the local colonial society and economy, but were dragged back by the demands of their relatives:

‘Several of the young men appear to be weary of the bush life, and manifest a desire to possess property of their own: but they are afraid that other natives would soon dispossess them of what they might acquire.’

A summary of the fate of the mission (written by the bookseller) and a transcript of the report can be read here.

The Rev. William Cowper also attended the four Protestant men out of the seven that were convicted and hung for the Myall Creek Massacre in 1838 (Reference 1, p30).

The Cowper Family and Land Grants

On the 24th of July 1820, the Governor of NSW, Lachlan Macquarie, proclaimed the accession of the new King, His Majesty George IV.

Part of the proclamation reads that the,

‘… inhabitants of [His Majesty’s territory of New South Wales and its Dependencies, etc] do now hereby, with one Voice and Consent of Tongue and Heart, publish and proclaim the High and Mighty Prince, George Prince of Wales, is now by the death of Our late Sovereign [George III] of happy Memory, become Our only lawful and rightful Liege Lord, George the Fourth … To whom we do acknowledge all Faith and constant Obedience …’

Amongst the prominent Inhabitants of the Colony who signed and subscribed to the Proclamation was Professor Jackson Pulver’s 4X great-grandfather, the Reverend William Cowper (see full Proclamation here).

In the same month as Governor Macquarie made his Proclamation, Thomas Cowper ‘requested a piece of the new King’s territory’ (Ref. 1, p17).

In the July 1820 files of the New South Wales, Colonial Secretary's Papers, we located a memorial from Thomas Cowper in support of his land grant application, a transcript of which reads,

Figure 10 - Memorial by Thomas Cowper for a land grant. Source: State Archives and Records Authority of NSW; Series: NRS 899; Reel or Fiche Numbers: Fiche 3001-3162. Accessed via Ancestry.com

July 1820

To His Excellency Lachlan Macquarie Esqre Governor & Commander in Chief in & over H. M. Territory of N. S. wales and its Dependencies

The Memorial of Thomas Cowper

Respectfully States

That your Excellencys Memorialist is second Son to the Revd W. Cowper [?] Chaplain at Sydney.

That memorialist is now arrived at the age of 18 and having been 2 ½ years employed for his own benefit and willing to make every exection [sic] in his power to prevent his being burdensome to his parent – has induced your Memorialist to solicit your Excellency would be pleased to indulge him with a Grant of Land with a view to settle and cultivate the Same,

And as in duty bound …..

The grant was recorded as being granted in 1822 - see the first entry in the table of Figure 11.

Figure 11 - Entry #79 in the Land Grant records of NSW, 1822 showing Tho(mas) Cowper’s land grant of 500 acres in the District of Camden. Source:1822 Land New South Wales, Australia, Registers of Land Grants and Leases, 1792-1867

The point that we are making here is that all these records concerning the Cowper family show that none of these men were Aboriginal. Instead, the Rev. William Cowper and his son Thomas Cowper were Englishmen, who were heavily involved in the colonial project of NSW. The research we have collected here on the Cowpers is a 10,000 word archive of their trials and tribulations in the Colony of NSW.

This research shows that the Cowpers were in correspondence with Governor Lachlan Macquarie, from whom they received very large land grants, and they had established themselves in the Camden district of the colony as a, ‘certain type of Englishman’ - The Englishmen of the Cowpastures - also known as ‘the Cowpastures gentry, a pseudo-self-styled-English gentry’ according to a local history group.

Based on this prominence of the Cowper family, it does seem hypocritical for Professor Jackson Pulver to make public pronouncements regarding the dispossession of Aboriginal peoples when her own Cowper family were so heavily involved in what the Professor believes is the ‘dispossessing’ colonial project.

For example, in 2008 Dr Lisa Pulver Jackson (as she then was) made a ‘Submission to Legislative Council Standing Committee on Social Issues Inquiry into Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage in NSW 29 February 2008’. She so-authored this submission in her ‘private capacity’.

In the submission, Dr Lisa Pulver Jackson quoted Prime Minister Paul Keating’s 1992 speech where he claimed that,

‘It begins, I think, with the act of recognition. Recognition that it was we who did the dispossessing. We took the traditional lands and smashed the traditional way of life’ (ibid., p4.).

In the body of the submission, the Professor supports the ideas that,

‘… governments must: acknowledge that current Indigenous disadvantage is a direct consequence of past government laws, policies, practices and attitudes…’ (p5.), and that ‘the ‘causes of the causes’ for Aboriginal Australians’ incarceration are manifold. They commenced with colonization and dispossession…’ (p24.)

The Professor thus appears to be a supporter of Keating’s claim that ‘we’ [that is, the non-Aboriginal Australians descended from the colonisers] and ‘our governments’ were responsible for the ‘dispossession’ of Aboriginal peoples of their lands.

However, nowhere could we find any record of the Professor herself acknowledging the part her own Cowper family played in this ‘dispossession’.

Surely the Professor must see that when her 3X great-grandfather, Thomas Cowper, was given a land grant in 1822 from King George IV, this must have directly led to the ‘dispossession’ of the tribal lands of the local Aboriginal people?

Has the Professor made [or should she?] a personal atonement for these historical actions of her own Cowper ancestors?

Mary Cowper

The next generation descended from Thomas Cowper is his daughter, Mary Eliza Matilda Powell (nee Cowper). A photograph purporting to be her exists, which clearly shows a woman from the middle class society of colonial NSW (Figure 12). This is Professor Jackson Pulver’s 2X great-grandmother.

From her obituary we learn that she too was born in Tyndale a small community on the banks of the Clarence River at Woodford Island, ‘an island in the Clarence river’, a location that Professor Jackson Pulver also claims as being the birthplace of her own ‘Aboriginal’ grandmother (see her claims above).

Figure 15 is a map of the Clarence River region showing the names of towns and islands which feature in the genealogical records of Professor Jackson Pulver’s Cowper ancestors - the ‘islands in the Clarence’ , Woodford and Harwood, the towns of Maclean, Tyndale and Grafton. In addition, there is even a small town called Cowper, which was named after Professor Jackson Pulver’s 3X great-granduncle, the 2nd Premier of New South Wales, Sir Charles Cowper KCMG (1807 - 1875). [See further reading below]. Is the Professor claiming that a town was named after her particular Aboriginal ancestor? That would probably be unique in Australian history?

Figure 12 - Said to be a photograph of Mary Eliza Matilda Powell, Professor Jackson Pulver’s 2X great-grandmother. [Mary Eliza Matilda Powell (nee Cowper) 1858-1929 - Date unknown].

The Professor claims that this woman’s daughter, Ada Beatrice Powell, gave birth to an Aboriginal girl ‘under a tree on an island.’ That baby the Professor claimswas her ‘Maori-looking’ grandmother. Source: Ancestry.com user gasman35 originally shared this on 23 Jun 2017

OBITUARY MRS. M. POWELL [Mary Eliza Powell (nee Cowper)]

The death occurred at Coraki on Tuesday, at noon, of Mrs. M. Powell, widow of the late Edward Powell. Both Mrs. Powell and her late husband were well known on the Lower Clarence.

Mrs. Powell, who was 72 years of age, was born at Tyndale, Clarence River, and was a daughter of the late Thomas Cowper. She resided in the district to within 10 years ago, when she went to Coraki to live with her sons.

… Mesdames H. Reeves (Sydney)*. J. Connolley (Kyogle), T. Robson (Woodburn). Chas Robson (Ruthven), and O. Connolley (Palmer's Island), are daughters, and Messrs. Richard (Toowoomba), Morris (Lismore), James, Roy, Jack and Darcy (Coraki), are sons of the deceased.

The remains were brought to Maclean on Tuesday night and interred in the Church of England cemetery on Wednesday morning, beside those of her father. The Rev. C. Rowe officiated.

Both the late Mr. and Mrs. Powell did their share of pioneering work in the early days. They lived in the district when there was very little settlement, her father being at Tyndale as far back as the fifties [1850s]

* [this the married name of Ada Beatrice Powell]

Source: 1929 Obituary, Daily Examiner (Grafton, NSW), 14 June 1929, p. 4

Mary Cowper was born in 1858 but her birth was not registered until 1860 (Figure 14). Her birthplace is recorded as Summervale. This is most likely the name of her parents house or property although we have not been able to confirm this. Some researchers might be tempted to conflate the ‘Summervale’ of Mary Cowper’s birth place with the ‘Summervale’ that was an Aboriginal Mission in NSW [the Walcha Aboriginal Reserve], but we believe the two locations are unrelated.

Figure 13 - Excerpt from the List of Aboriginal Reserves of NSW. Walcha is located about two hundred kilometers south west from the Clarence River region, where Mary Cowper was actually raised. Source: Wikipedia

Figure 14 - Birth and Baptism record for Mary Eliza Matilda Cowper. Source: NSW Births Deaths & Marriages

Figure 15 - Towns and Islands in the Clarence River region. Source: Googlemaps

The daughter of the above Mary Eliza Matilda Powell (nee Cowper), was Ada Beatrice Powell [1880 - 1969].

Professor Lisa Jackson Pulver has claimed at various times that this Ada Beatrice Powell gave birth to an Aboriginal girl, who was

‘… born third tree from the left on a small island in the beautiful Clarence River, on the Northern New South Wales Coast.’ (listen here from 04:40)

or was

‘… born up on the far north coast of New South Wales in [sic] an island in the mighty Clarence River’ ( interview )

That supposedly Aboriginal girl, the Professor claims, was her ‘Maori-looking’ grandmother, Clarice Mary Smidt (nee Powell), a photograph of whom the Professor has supplied purporting to be her (Figure 16).

Figure 16 - An excerpt from a 2020 Presentation by Professor Jackson Pulver, which shows a photograph of a woman from the ‘Powell’ family who the Professor claims is her ‘Maori-looking’ Aboriginal grandmother, ‘born on an island in the Clarence , claimed to be her Aboriginal grandmother ‘born up on the far north coast of New South Wales in [sic] an island in the mighty Clarence River’. Source: Interview

Clarice Mary Smidt (nee Powell) was born in 1900 and passed away in 1986. We find it very hard to believe that this woman, coming from the colonial Powell and Cowper families, was ‘born under a tree on an island in the Clarence River’ in 1900.

Prominent colonial families did not allow their daughters to give birth under trees.

It is our speculation that Professor Lisa Jackson Pulver is ‘just making up’ this family myth to add narrative to her claim that Clarice was Aboriginal. We suspect that the Professor thinks that her readers might be more convinced that her grandmother was Aboriginal if they believe the story that she was born under a tree on an island.

But just how likely is it that this woman was an Aboriginal girl born under a tree in 1900?

She came from a long line of the Cowper family, who were celebrated at a 2009 Civic Thanksgiving service where Sydney’s Archbishop Peter Jensen praised the Rev. William Cowper as a "sensational nation-builder, making sure that the true Christian gospel was written into the title deeds of the new nation".

This 2009 Cowper Bicentenary was organized by his descendants and included historical talks, a family picnic and the Civic thanksgiving attended by NSW Governor Professor Marie Bashir.

As reported on the Sydney Anglicans website,

‘William Cowper arrived in NSW on 18th August 1809. As minister of St Phillip's Sydney for 49 years, he must have baptised, married or buried, most of the population. Cowper was instrumental in setting up many of the social institutions that helped NSW move from a penal colony to a nation. It is a gauge of his significance that when he died in 1858, Sydney closed down and 25,000 people lined the streets for the funeral. Archbishop Jensen spoke of Cowper's pivotal role in institutions such as the Benevolent Society and the Bible society, but also his work among aborigines.

"At a time, believe it or not, when many people regarded the aboriginal people of our land as though they were merely a link between the animal and the human kingdom, extermination and murder were practiced, Cowper stood valiantly for truth and love. Here is a part of his vision for who we should be, that is yet to be fulfilled. The original people of Australia must always be given a special place of honour and affection. In word and deed, Cowper testified to that in his day and he still speaks to our consciences." - The Sydney Anglicans

As far as we were able to determine, none of the Cowper descendants at this 2009 Civic thanksgiving raised the prospect that they were Aboriginal.

The Cowper family operate a website on their extensive family tree and if there was Aboriginality in the family then there should be a record of it in this independent family research. In the family branch of Thomas Cowper, Professor Jackson Pulver’s 3X great-grandfather, there is no mention of any of the descendants being Aboriginal. In particular, there is no mention of Ada Beatrice Powell giving birth to an Aboriginal girl under a tree on an island in the Clarence River.

Similarly, we have found no evidence that Professor Lisa Jackson herself attended this Thanksgiving as an Aboriginal member of the Cowper family.

Now, maybe we are wrong because we don’t know of some deeply hidden secret in the family - perhaps, for example Ada Beatrice Powell had a secret affair with an Aboriginal man and the issue, baby Clarice, the Professor’s grandmother, was in fact Aboriginal by descent. Or maybe baby Clarice was the result of an illicit relationship between one of men of the Powell household and an Aboriginal woman and Ada agreed to ‘adopt’ the child into the family as her own.

Without the discovery of say, a personal diary detailing these events, we just can’t know if these are valid reasons as to why Professor Jackson Pulver believes that her grandmother Clarice was Aboriginal. Certainly the Professor herself has never publicly provided any real or documentary evidence to support her Aboriginality claims for her grandmother.

So, to summarise this Part 6 post of the Professor Lisa Jackson Pulver story, we have constructed te following partial alleged maternal family tree up to the branch of Mary Eliza Matilda Cowper (Figures 1 & 2). All family members researched so far have their ancestry originating in England or Ireland. There is no evidence of any family members so far having any Aboriginal ancestry.

So, if Professor Jackson Pulver is telling us the truth, that she is in fact Aboriginal on her mother’s side, then the last remaining branch of the family that could provide any Aboriginality is the via the Small family [see Eliza Small in Figure 1].

Was Eliza Small Aboriginal?

We will provide our research findings on what proved to be the fascinating story of Eliza Small and her family in our next and final installment of the Family Tree of Professor Lisa Jackson Pulver.

Reference 1 - Bolt, Peter, G., The Indispensable Parson, William Cowper (1178-1858), The Life and Influence of Australia’s First Parish Clergyman, 2009.

Further Reading

1. William Cowper Dean and Archdeacon of Sydney

William Macquarie Cowper, who was the half brother of Thomas Cowper, and who was the dean and archdeacon of Sydney in the late 1800s. He was thus, Professor Jackson Pulver’s 3X great half-uncle. There is no evidence that he identified as Aboriginal.

Figure 17 - Photograph of William Macquarie Cowper, Dean and Archdeacon of Sydney. Source: ADB

2. Aboriginal Childbirth

Figure 18 - Aboriginal woman in labour, Central Australia, ca1930, photographer unknown

The following description of Aboriginal childbirth is from a book by the anthropologists Ronald and Catherine Berndt [with John Stanton], ‘A World That Was’ [MUP, 1993]. From the book cover,

‘In 1939 Albert Karloan, a Yaraldi man, urged a young anthroplogist, Ronald Berndt, to set up camp at Murray Bridge and record the story of his people. Karloan and Pinkie Mack, a Yaraldi woman, possessed through personal experience, not merely through heresay, an all but complete knowledge of traditional life. They were virtually the last custodians of that knowldge and they felt the burden of their unique situation. This book represents their concerted efforts to pass on the story to future generations.’

This description of Aboriginal childbirth is of interest to this post on Professor Lisa Jackson Pulver because it perhaps can provide readers with some idea of how the Professor’s Aboriginal grandmother may have been ‘born under a tree on an island’, if indeed that claim is true.

The two informants for the Berndts, the Aboriginal man, Albert Karloan, and woman, Pinkie Mack were born in 1864 and 1869 respectively. (ibid. p. xxi).

They were thus contemporary with the Cowper and Powell women in Professor Jackson Pulver’s family, who were presumably involved with the birth of the Professor’s Aboriginal grandmother Clarice Clarice Mary Powell (Smidt), ‘born under a tree’ on Harwood Island, Clarence River, in 1900, the daughter of Ada Beatrice Powell, born in 1880 from her mother Mary Eliza Matilda Cowper, born, also on an island in the Clarence River, in 1858.

‘Albert Karloan was the last man alive (in 1939) to have gone through the whole Yaraldi initiatory sequence, which he completed in 1882; and Pinkie Mack, who was born in the bush, had also gone through an initiation ritual, albeit in an abridged form’ (ibid. p. xxi). At this time the Yaraldi society and culture (in South Australia) was being transformed by European influences so the ‘traditional’ knowledge held by Karloan and Mack may have been not completely ‘pure.’

Nevertheless, their description of childbirth we believe may be a useful, general proxy for the childbirth practices for ‘traditional’ Aboriginal women in say, the Clarence River region on NSW, where the Professor claims her Aboriginal grandmother was born. We will leave it up to our readers to decide, based on the photographs and the history of the Cowper and Powell families we have provided, whether the Professor’s female ancestors were actually Aboriginal and born in the bush, under a tree’ in the traditional Aboriginal way.

From the Berndt’s book,

‘In spite of the dangers facing an embryonic child, most, we were told, achieved entry into Kukabrak society. Prior to its arrival, however, the pregnant woman would be kept under surveillance by the older women of her camp who were acquainted with all the movements she would be likely to make…

[the older women of the camp would say -mentioning the name of a pregnant woman -] mimini poliwolin. "Yarandun ngaleiin?'' A a, kruwui-ungk djining: mantin knokin itjin miwi landjalan.' - 'That (name] l woman child-forming', one would say to the other. ‘How do you know?’, would ask the other. [Exclamation], menstruation after copulates; slowly see that one's stomach swelling.'[Note that for stomach' the word miwi is used.]

During pregnancy a woman could carry out more or less the same tasks as she did ordinarily, although she would rest more during the final stage. Also, as already mentioned, she tended to eat more than she normally would:

‘Talwu tak nguntuwal' Meind?''Indanjeri wiranind [aulwa] 'Yarap wirin puli?' *Krungan krantewolini!''A! Talwai tak maltewar, ngaraiyu, tak wonitji buli tapurani nangkeriwolin.'A! - Don't eat too much', she would be warned. Why?', she would ask. Because [it is this way that] you will become ill', she was told. How bad [for] child?', she would ask. Listen [become too] big! [Exclamation]. She would continue, Do not eat too much; be careful: eat so that the child will come out easily”. The expectant mother would reply, [Exclamation].

The matter is not to be left there. As will be recalled, a pregnant woman was forbidden (arambi) to eat several different foods, especially those that were fatty. These were classified under yilkunin itjanan miwi narambi (move that stomach taboo).

In the contact period, as in the early 1940s, pregnant women would not usually eat mutton, lamb, veal, beef or pork because of their fat. The pailpali (fat) taboo was enforced about two months before the birth was due; the eating of any kind of purgative root was also strictly forbidden, since these could cause a miscarriage or at least injure the unborn child permanently.

Sexual relations would continue intermittently until the fourth month of the pregnancy, although as soon as she became dilated the man would not lie on her. Instead, she might lie back on the ground, resting on her elbows, with knees drawn up and legs apart, and the man would kneel between them as she raised herself somewhat by using her elbows as a lever: he would lean forwards, effecting entrance while supporting himself with his knees and hands on each side of her body. The other way was for a woman to kneel with legs apart, bending forwards, resting upon her hands and elbows. The man would kneel behind her, moving forwards to adjust his penis; he might or might not rest his hands on her back. After the fifth month, a man would usually limit intercourse with his wife to two to three times a month. In all cases, he would be careful not to force his penis too far into her vagina because any movement against the murilbilin might injure the foetus.

During the latter part of pregnancy, when a woman was less interested in sexual relations, she welcomed her husband's attention to other women and encouraged him to avail himself of the kuruwolin. Towards the eighth month, it became 'dangerous' for a prospective mother to have coitus. It was said that if she did the child might slip and the result would be a miscarriage.

However, about a fortnight to a week before the impending birth a husband had what can perhaps be called ceremonial intercourse with her, taking the first position mentioned above. The intention was, supposedly, for the semen either to enter the uterus or to be lodged within the vagina and not to be released until birth took place. It was believed to help in ensuring a comparatively easy delivery, because the channel through which the child was to pass was rendered slippery. Karloan said he had been told about this by Elizabeth Maratinyeri, a Tangani who died during the 1920s and the wife of Peter Gollin.

She was a well-known putari and midwife who had served her apprenticeship with Yaraldi and Tangani female putari. This also brings up a further point: there was no embarrassment in the part of men and women discussing such intimate details.

From the time she was big with child, a period designated by the expression ‘when the uterus falls', a woman was instructed by a putari (or by a mother's or father's sister or an elderly friend) to lie only in specified ways when resting, since to be careless in this respect could injure the unborn child. She would be advised:

Tal thropa inandju wirangungai mari; lambak mangkewolamb, buritj itji boli tarpu talwuritji pinkil wirangwolin thumpu itji thalpuli. - Do not lie [thus] because of illness coming; this way is good, so that the child coming out does not fall wrongly [but] alive that one comes.

She would reply:

A ikapa lewani nangkewolani. - Yes, I will sit correctly.

A pregnant woman was to lie not on her belly or on the left side, but on her back or on the right side to prevent the child from ‘falling' (pinka itji puli, fall that child).

During the period of her pregnancy she would remain in the camp that she shared with her husband even to give birth. However, in some cases she was taken into the bush to a specially prepared camp. Meyer, reported that a Ramindjeri woman near her confinement would leave the encampment, with some of the women to assist her. We were told that a birth would take place eight to nine months after conception: if it were earlier, premature delivery would be involved. Under such circumstances, there was always the risk of the child's death or injury.

Beyond the normal period of expectation,the birth of a child was bound to be difficult. So, an easy birth depended on a range of factors: on the avoidance of fatty foods, on adherence to the narambi taboos, on prenatal care including the diminution of sexual activity, and on the general physical condition and health of the woman.

Taplin said that although native women suffered considerably in childbirth (some more than others) they generally suffered less than 'white’ women. Be that as it may, there is no reliable evidence to enable us to gauge the relative suffering of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal women in such circumstances. (Ourselves, we would suggest that such a distinction cannot be drawn.)

Apart from questions of health and the physical care of an unborn child, attitudes towards childbirth were significant. Yaraldi, from what we can gather, regarded childbirth as a natural occurrence, not something to be avoided - unless other factors intervened. It was considered to be a fulfilment of an important part of a woman's marriage arrangement and also to be of vital concern to the enhancement of her personality a means through which she attained status as an adult and a woman.

Some women were quite calm right up to the actual labour pains and went on with the making of a mat or net; others were much less so.

Taplin noted that instances of death in women during childbirth were rare (Diary and Point McLeay marriage and birth Register): he referred to three, of whom two were sisters, both named Pitembiteperi; one married Old Fred Wassa and the other married Loru Nompe, called Old George Harris.

The cause of their deaths, he said, was obstinate metritis, which set in immediately after the children were born.

The information on birth was primarily from Karloan, who obtained it from his wife's (Flora Kropinyeri) mother, Jean Perry, the sister of Peter Martin and Tommy Martin and the daughter of Old Dick Martin; she married William Kropinyeri and was recognized as an excellent midwife. The information was supplemented by details given by Pinkie Mack.

The usual pattern of the birth was that, on feeling the onset of labour pains, a woman would sit down in her and her husband's camp while he left to sit on the opposite side of the main camping area or at least some little distance out of sight behind a windbreak. Some men, at such a time, would prefer to go out hunting or fishing to take the matter off their mind and be diverted from worrying.

Others, we were told, would be quite apathetic about the impending event. Anxiety on the part of a man depended on whether or not the child to be born was his first; men whose wives had had several children would take it in their stride and laugh at an anxious expectant father, saying he would not be so worried when the had experienced this situation several times. Old men too would reassure him of a successful outcome.

There were cases in which no other woman and no putari were available when, for instance, a man and his wife were on walkabout, unaccompanied by other persons. In such circumstances, it was necessary for him to deliver the child. However, such examples were rare and people usually did not travel alone especially at such a time without another woman who could help in an emergency.

The posture of a woman in giving birth was to kneel with legs apart, sitting back on her heels with the feet resting on the ground, soles uppermost. (Taplin, mentioned a similar way of sitting in this context.) She would lean back against a squatting woman immediately behind her, usually one who was an apprentice to the putari in attendance and was gaining practical experience. The putari would feel the mother's abdomen by passing her hand gently over it, as well as the vulva which had become dilated with the impending birth.

This was done in order to see whether the child was ready to come out. If it was, the putari turned her towards the left side, with the apprentice drawing the woman well back and holding her firmly with both arms around her waist.

On occasion, the putari might need to put her hand inside the muli (vulva) in order to turn the child around so that it would emerge head-first. As the child was about to come out, the apprentice would press her knees into the woman's back, at the same time holding her securely so that the child would be delivered without delay; the afterbirth fluid (called prenguki), in which it was said the child floated while in the uterus, also came out at this time. The putari would ease out the child and break the umbilical cord (bulangi) with a twist of her hands.

That was the conventional scene. Pinkie Mack said that before the last three pains, the putari would call to the child to come without delay. She also said that the mother's abdomen was massaged and, if necessary, the putari would put her hand into the vulva to help the child, lifting it and saying, Munga-atler - Keep quiet for a while.

As the apprentice held the mother tightly and pressed her knees against her, the putari pulled taut the skin on the upper part of the abdomen, holding it (perapun mungkeri; Piltindjeri dialect - to lift up the stomach) in order to feel the child move further down into the cup (i.e., the pit of the abdomen).

The mother cried out (kaikundul) in pain for the child to come. The child heard this and came more rapidly.

“Today', Pinkie Mack said, 'the child does not hear its mother's cry’; the reference in the phrase, Kaikundawun kung kungambulaan polul' - You call out he will hear that child - was to the old days. ‘This is a sad thing', she added, because not having heard its mother's voice at delivery the child will not be good, for the voice of its mother makes them good'.

Pinkie Mack had acted as a midwife at Point McLeay Mission and had been responsible for attending to the birth of seventy-two babies. The newborn child was placed on a fur skin prepared for the occasion. It was not washed but before being wrapped in the fur, the part of its navel cord that was still attached was tied with a piece of fibre. If this were left too long the navel would protrude when the child grew; if too short, it would retract, leaving a deep depression … a fragment of the navel cord was either buried or used to create or reinforce a ngengampi relationship.

After the birth the mother would lie back exhausted in the arms of the apprentice. The latter would ease her up and pressing her hands on the woman's left side above the thigh would force out the afterbirth blood (mawandi-kruwui) and liquid (buli) the latter was considered to be the semen from the woman's act of ceremonial coitus a week or two before the surplus menstrual blood unused by the growing child (kruwui) and the afterbirth (nawandi, so named after the uterus). All of this would be buried in a scooped-out hole, burnt in a fire or, preferably, put in a tied-up skin and disposed of out in the bush.

The mother did not normally squat over a fire after giving birth, but when there was a severe haemorrhage she would do so. Usually she was quite worn out after her experience, especially when the birth was a difficult one, and she was sometimes supported by the apprentice holding her up from under the armpits. This occurred, however, only in those instances when the mother was depressed, when she said, Wirina ngap prat-thulin - Bad me to give birth thus. Yet this soon passed, so we were told, and a haemorrhage rarely lasted beyond a day.

Taplin commented that the mother of a newly born child generally recovered rapidly, and added that he had known a woman to walk two miles on the day following her confinement. Much depended on the woman's health. We were told that she would rest for two or three days before taking up her normal routine tasks and looking after her child, but that some women did not need this short period of recuperation. After completing her duties, the putari and her assistant would cleanse their hands thoroughly with wild witjeri (pig-face) which grew plentifully in nearby swamps where samphire bush was to be found. [Witjeri was used generally for cleansing the hands as well as other parts of the body: the spongy leaves were squeezed and their salty water acted - so it was said, like magnesia. The hands and/or body were wiped with soft wolokaii grass.]

The father was informed of the result soon after the actual birth. He was, in ideal terms, pleased that the crisis was over and that his wife was no longer in pain. Although people emphasized that the child's sex was irrelevant, that its parents were equally pleased whether it were a boy or a girl, male members of the father's clan had a preference for a male child. In most cases, a father would not need to be informed if the child were healthy and had cried out on birth if the crying was delayed, the cause would be put down to the fat a mother had eaten.

On hearing the crying, he and his wife's father would call out to the mother, Pritjinin mutj poli ngatji ngirin - Strong child of me crying. All the people in the vicinity would comment on this, laughing among themselves and saying, "What a happy child it is!'

If the child did not cry or only whimpered a little, they would say, Muritjil naramb?' - Why is it quiet? ie. naramb narambi, taboo, silent or constrained - and they would shake their headsin sadness implying that they all knew why-the mother had eaten some fat, not enough to make the baby sickly but enough to make it uncomfortable.

Soon after this, however, a father would go over to his camp to see the child and the mother: he would comment on the healthy appearance of the child and tell his wife what a fine baby it was. Usually some older men (his own and his wife's relatives) would walk over with him and they would talk about the child, predicting what kind of an adult it would turn out to be.

For the first couple of days, a father's mother or mother's mother or father's sister or mother's sister of the mother would care for the newly born child until the mother was ready to take over these responsibilities; one of these relatives would also obtain and prepare her food. Generally, she would not breast-feed it for at least a day after the birth when the child was categorized as ngumbuli (given milk).

While the cries of a newly born child were welcomed, such cries were not considered so desirable afterwards. Some babies were touchy - they would cry all day as well at night. Everyone would be tired of the noise.

In desperation and not knowing why it cried and being unable to soothe the child herself, a mother would cry out, ‘Tanath ian bantul!' - Would not that [child] been born. In surprise a grandmother (or one of the woman's clan relatives) would ask, 'Meind?' - What for?. The other would reply, ‘Perkul ngirin’ - Too much crying.

The grandmother would say, Ur!' (an exclamation indicating surprise mingled with a warning, but not uttered in anger because she knew the mother did not mean what she said). Then she would continue, ‘Inumba ikan-ngani-in p’rumpan unguk ngarakal’ (We will smoke him later on tomorrow).

The next day the grandmother would build a fire upon which were piled leaves or branches of the watji (polygonum bush) with a covering of light branches: this would cause billows of smoke. The child would be held over this and, breathing in the smoke, would stop crying. After that experience the child supposedly would cry for only a little while, but never sufficiently to annoy its mother or other camp members.

There was no ritual at the birth of a child, except indirectly through the ngengampi. The natural act of giving birth was in itself a ritual manifestation which brought together the physical and spiritual attributes of a human being. The implications of his and her life were foreshadowed in his and her first appearance from the womb, as a crying or uncrying child, as noisy and active or quiet, constrained and naramb. These were contrasts which in themselves exemplified the basic qualities of Kukabrak men and women. With that composition, Kukabrak children entered their social world.

- ‘Childbirth’ from A World That Was, Berndt, R.M., Berndt, C.H. & Stanton, J.E., MUP, 1993, p.140-44.

Figure 19 - Source: Childbirth’ from A World That Was, Berndt, R.M., Berndt, C.H. & Stanton, J.E., MUP, 1993

Figure 20 -Source: Childbirth’ from A World That Was, Berndt, R.M., Berndt, C.H. & Stanton, J.E., MUP, 1993

Figure 21 -Source: Childbirth’ from A World That Was, Berndt, R.M., Berndt, C.H. & Stanton, J.E., MUP, 1993

Figure 22 -Source: Childbirth’ from A World That Was, Berndt, R.M., Berndt, C.H. & Stanton, J.E., MUP, 1993

Professor Jackson Pulver has not, to our knowledge, provided any detailed information about the birth of her Aboriginal grandmother beyond the fact that she was ‘born under a tree on an island.’ This is a little surprising to us given that the Professor strongly identifies as an Aboriginal herself and is a university lecturer and scholar and makes claims such as,

‘… two of my grandmothers are Aboriginal … yeah, so I'm proudly standing here … fiercely Aboriginal and don't anyone forget it … eeeee’

We would have thought that a scholar, such as the Professor, would have been able to research the birth of her Aboriginal grandmother a bit more thoroughly than just she,

'… was born third tree from the left on a small island in the beautiful Clarence River, on the Northern New South Wales Coast.’ (listen here from 04:40)

The Professor has provided no cultural details or records of her grandmother’s birth confirming her Aboriginality. However, we do know that there was interest in the Aboriginal women of the Clarence River region in the same period as Professor Jackson Pulver’s maternal ‘Aborginal’ ancestors were being born there.

In the late 1800s, a famous series of historic photographs was produced by the German photographer John William Lindt. In 1873, he photographed a number of Aboriginal subjects from the NSW north coast, in particular of the people of the Clarence Valley.

Lindt created what many believed to be the realistic depiction of what traditional life had been like for Aboriginal people before and during the early years of colonisation of the Clarence River region in the mid to late 1800s.

In the Figure 23 below, the Aboriginal woman in traditional dress photographed by Lindt, ‘Mary-Ann of Ulmarra’ is believed to have been the Mary Ann Cowen

Figure 23 - Simply called 'Mary-Ann of Ulmarra', this was one of 36 portraits taken by German photographer John William Lindt in 1873. (John William Lindt). Source: ABC

Figure 24 - Said to be a family photo of Mary-Ann Cowan [in normal colonial dress] feeding the chooks on the far north coast of NSW which helped identify one of the Lindt photographs.(Source: Cowan family ABC )

The Town of COWPER - Named After Professor Lisa Jackson Pulver’s 3X great-granduncle, Sir Charles Cowper KCMG (1807 - 1875), 2nd Premier of New South Wales (26 Aug 1856 – 2 Oct 1856).

The Village of Cowper is situated on the right bank of the Clarence River, at the point where the ana-branch, known as the South Arm, leaves the main stream. It is sixteen miles below Grafton, and within the Municipality of Ulmarra. When land in the district was thrown open for selection, the site of Cowper was reserved for a township, and during the Cowper Ministry, in 1870, it was surveyed and named after Sir Charles Cowper. In August, 1870, the allotments were submitted to public auction, but it is only within the last twelve mouths that its actual settlement may be said to have commenced. During the year 1873 a neat and well furnished Public School was erected, but it was not opened until July, 1874, and since that time an average of about 40 scholars has been regularly maintained ; lately, a valuable addition in the shape of a weathershed has been made. Attached to the school is a comfortable teacher's residence ; altogether the building reflects much credit on the inhabitants of the neighbourhood. The business community is at present not very large, but buildings are rapidly springing up, and from its pleasant and central position, it is destined to become at no very distant period a prosperous and important township. The principal products of the locality are maize and sugar-cane. Source