Spiritual Subsistence or Heroic Materialism? It's Our choice

Heroic Materialism (Note 1)

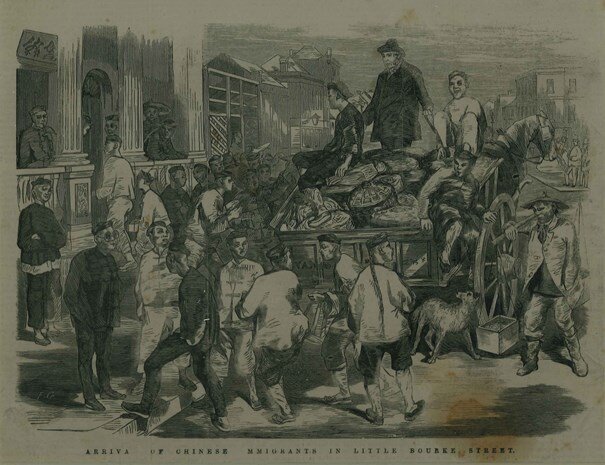

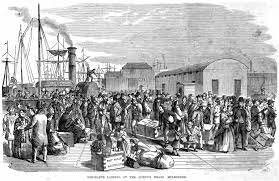

Imagine an immensely speeded-up movie of Melbourne during the last two-hundred years. It would look like a frenetic rush of man and crane, fuelled by the wealth from sheep, wool, grain and gold. This tremendous upheaval, lurching forward by boom and bust, and at times brutal and violent, can’t be dismissed or sneered at because, in the end, it has lifted countless millions of immigrants and ordinary people out of poverty and allowed them, their families and their society to flourish.

Modern Melbourne

Melbourne 1841 (State Library Victoria)

Artist’s impression of Melbourne in 1835, as seen from "the Falls". Source: Gordon H. Woodhouse, photographer, and Schell, Frederic B. artist, circa 1925, State Library of Victoria.

However, as British art-critic and author, Kenneth Clark tells us in his book, and the BBC television series, Civilization, when speaking of New York (we use Melbourne as our proxy),

“New York was built to the glory of mammon - money, gain, the new god of the nineteenth century. So many of the same human ingredients [that were used to build the Gothic cathedrals] have gone into its construction that at a distance it does look rather like a celestial city. At a distance. Come closer and it's not so good. Lots of squalor, and, in the luxury, something parasitical. One sees why heroic materialism is still linked with an uneasy conscience. It has been from the start. I mean that historically the first discovery and exploitation of those technical means which made New York possible coincided exactly with the first organised attempt to improve the human lot.” - (ibid. p 322 and video clip here)

Immigrants flocked to Melbourne and, despite life for many of them starting in the slums, ultimately the productivity and the progress achieved by Melbournians has lifted everyone out of poverty and provided a permanent safety net for those that still fall through the cracks. Melbourne is a shining example of Clark’s, ‘organised attempt (and success) of improving the human lot'.’

We now need to ask ourselves, with respect to Melbourne, could ‘heroic materialism’ still be ‘linked with an uneasy conscience’?

To us at Dark Emu Exposed, the answer is an obvious no. We are all heroic materialists now, for better or worse. And for anyone who wants to reject this ‘materialism’, our society is so rich that the opportunity exists for those rejectionists to set up a ‘materialism-free’ lifestyle somewhere in Victoria - on a farm, in a city commune, in a religious sect, or even in a hermit’s shack in the bush or by the coast, should they wish to do so.

But is this enough for the committed anti-capitalists and political opportunitists within our society? Do they still want our society to maintain an ‘uneasy conscience’? In our opinion they do, and they are using a re-interpretation of our Aboriginal and Colonial history, and the new ‘sustainability meme’, to do it.

This is why, it seems to us, authors such as Bruce Pascoe in his book Dark Emu, overly emphasize, ‘The Land Grab’, the ‘Frontier Wars’ and the ‘Aboriginal massacres’ that supposedly led to the ‘dispossession’ of Aboriginal peoples in places such Port Phillip, and where Melbourne now stands. We are constantly being reminded by our taxpayer funded ABC, SBS and NITV that we need ‘truth-telling commissions’; our Victorian Labor government has stoked our ‘uneasy conscience’ by initiating the ‘treaty’ process; and a new, reverse-land grab is under way, under the banner of the slogan, ‘Always Was, Always Will Be’ Aboriginal land, despite what International Law, Commonwealth Law and indeed our own home Certificates of Land Title, with its prominent Victorian Crown Land Title stamp, tells us is decidedly not Native Title or Aboriginal land.

It seems to us that the activists are deliberately endeavouring to resurrect a new ‘uneasy conscience’ to push their political agenda along, and remind us of the supposedly ‘Aboriginal nirvana’ that was in place, and then destroyed, when Melbourne was founded in 1835.

In 1835, John Batman, the leader of the Port Phillip Association signed an agreement or ‘Treaty’ (later repudiated by the British Colonial Governor) with local Aboriginal people for use of the land that was to become Melbourne.

Early Pre-colonial Melbourne : Aborigines on Merri Creek by Charles Troedel

Spiritual Subsistence instead of Heroic Materialism

The Aboriginal societies living in the Port Phillip region had survived brilliantly as hunter-gatherers for tens of thousands of years. Their societies however, were based on what could be called ‘spiritual subsistence’. They produced just enough food and material goods, enabling them to survive day-to-day, using what they believed were spiritual means (increase ceremonies). They then spent the rest of their time and energy on family and kinship issues, and art, cultural and spiritual interests. They did not embrace ‘heroic materialism’, either by choice or by accident; and that was fine as it worked well for them for generations - until one day when another culture of men, who were heroic materialists, arrived on their shores.

This arriving British culture was spiritual as well, it being based on the Christian religion, but it also had embedded within it, ‘heroic materialism’ in the form of the biblical, ‘go forth and multiply.’ In addition there was another spiritual element within this new colonisation in the form of ‘evangelicalism’, the desire to offer the Christian God and spirituality to the Aboriginal peoples .

Aboriginal societies found to their detriment that they could not withstand the consequences of this new heroic materialism and its Christian spirituality. Within two or three generations, the traditional Aboriginal societies of the Port Philip region, the Boon wurrung and the Woi wurrung had collapsed.

Palm-held tools of Mankind : Hand-held ground-edged stone axe made by one man of the Kurnai - found in the 1970s near Foster, Victoria after being hit with a mower (see steel blade cut marks) and a computer mouse - the product of literally thousands of men and women from dozens of countries and cultures.

In the overwhelming of cases, when two societies clash, or come into conflict over resources, the victor is almost always the society with the superior forces, materials and systems.

Australian Aboriginal society may have been the world’s first inventor of a major piece of technology that fitted into the palm of a man - the ground-edged stone axe; but it failed to develop it much further. Consequently, Aboriginal society was no match, in 1835, against a materially much richer, European, colonial society, a society that had the steel-axe, but also all the elements which ultimately lead to the production of a palm-held device with staggeringly huge power - the computer mouse.

One of the reasons why Aboriginal societies ‘failed’ to produce a material kit showing not much more complexity than a stone, ground-edged axe was that they did not develop more advanced ‘divisions of labour’ within their economy.

In pre-colonial Aboriginal societies, the division of labour was rudimentary - men, women and children each had their own unique, well defined labour duties within the society. Each man was a self-contained generalist who made all his own material tool kit, although there were a few individuals who added some additional specialist skills, such as being medicine-men and women, pituri and quarry-stone custodians, sorcerers and mid-wives. It was also extremely rigid, with severe penalties, including death, for those buddying ‘entrepreneurs’ who ever attempted to undertake roles or jobs, which were outside their allowed initiation level or allotted tribal career paths.

As a way of comparison, consider the crafting of an axe. In traditional Aboriginal society each individual man made his own stone axe by selecting the required stone, working and grinding it with his own hands over very many days, while he sung the required chats to imbue it with the required spiritual properties. A European craftsman however, fashioned his much stronger and sharper steel axe with materials, equipment and technology supplied by a hundred other people, some in Europe, (machine makers and designers) some in Australia (miners of the iron ore) and some in Asia (factory workers who blasted the iron-ore to make the tensile steels). The productivity of the European compared to the Aborigine (see Note 2) was phenomenal in that he could produce a steel axe head in a matter of minutes, albeit with the indirect assistance of hundreds other people in a supply chain built on the division of labour.

As this video below shows, is it any wonder that Aboriginal society just did not have the material means to prevent the colonisation of Melbourne in 1835 by the materially advanced British?

There is nothing wrong with admitting that a stone-age Aboriginal craftsman was anything but a highly skilled, one-man manufacturing machine - making one tool at a time, imbuing it with special operating spiritual ‘powers’ by singing a chat as the stone was ground. But despite this attention to detail and care, the final product was still “primitive”, when compared to a steel axe, fashioned by an industrial-age craftsman using the technology developed by hundreds of other humans, each drawing on the knowledge of several civilizations. A stone axe was to be no match for a steel axe produced with metallurgy, electricity, mathematics, chemistry , physics and machines.

Aboriginal societies were brilliant hunter-gatherer economies that were able to survive on this most inhospitable of continents for some 50,000 years. But if the intellectuals and activists of today want us to believe that Aboriginal Society was a ‘civilization’, and of equal worth in promoting the welfare and flourishing of mankind then, in the words of the inimitable Darryl Kerrigan, ‘they’re dreaming’.

And the proof is in the pudding - no Australians, let alone the intellectuals, ensconced in their cushy ivory towers in Melbourne, choose to live a traditional, pre-colonial life today. We have all voted with our feet, in varying degrees to adopt heroic materialism as our preferred way of living.

To our minds, here at Dark Emu Exposed , cultural relativism might look good on paper to an intellectual or activist, but in real life it is just a myth, or even a Sacred Cow, which mainstream Australians are too polite (or afraid?) to question in public. Privately however, we all know that, ‘the world’s oldest continuous culture’ had its deficiencies, which ultimately lead to its demise when faced with a more materially powerful British culture [which by the way is the survival product of the same length of time, 70-100,000 years, and so it too could be called one of, ‘the world’s oldest continuous cultures’ (as also for the rest of mankind given that we all did originate at the same time in pre-historic Africa - but we will leave this ‘problematic’ point to be addressed in another future blog-post)].

Note 1 - Based on Kenneth Clark’s, Civilization, Harper & Row, 1969, page 321ff

Note 2 - It appears that Aboriginal society may not have appreciated the value of the concept of ‘productivity’. For example, when an Aboriginal tribe, the Yir Yoront on the west coast of Cape York, were given a much more efficient steel axe, which reduced the amount of time it took cut trees compared to their usual stone axes, it was found that,

‘Any leisure time the Yir Yoront might gain by using [a] steel axe or other western tools was not invested in “improving the conditions of life,” nor, certainly, in developing [any] aesthetic activity but in sleep–an art they had mastered thoroughly’. - Source , page 6.