Why Isn't There Any Physical Evidence of the So-called 'Frontier Wars'?

This post is the second in our series on the so-called ‘Frontier Wars’ - Truth or Fiction? [Part 1 here]

Professor Pascoe is a believer of the idea that there was a violent dispossession of Aboriginal peoples during the settlement of Australia, leading to their removal from their tribal lands, or their outright killing by the settlers. (See Professor Pascoe’s book, Convincing Ground as well as numerous interviews and lectures).

One of the main academic sources of this version of our colonial and Aboriginal history is Professor Henry Reynolds. Reynolds has been the main proponent of the ‘Frontier War’ theory, which contends that Australia had a very violent frontier history, resulting in a very high number of Aboriginal deaths due to indiscriminate shootings and massacres.

Indeed, Reynolds goes further and says we need to face up to this very violent past and hold certain people to account and we today need to take responsibility for their supposed actions,

“We really have to look at and take responsibility for those who were responsible for the settlement, if you like, the conquest of north Australia after 1850; and in particular, after the Australian colonies became self-governing. So that the responsibility for Queensland and the Northern Territory belongs to those colonial politicians who represented democratically elected parliament…say…Samuel Griffiths [was particularly] responsible for the conquest of north Australia because Queensland had a much larger population [of Aborigines] and the settlement there was particularly violent.

It was the most violent place in Australia and Samuel Griffiths, unlike many of the frontiersman who probably thought it was quite legal to shoot Aborigines, to shoot the blacks, Griffiths was a great jurist; and he was of course, the founding chief justice of the High Court of Australia…and yet as a colonial politician in the 1870s and the 1880s, he was directly responsible for massive killing out in the frontiers. And we just have to come to terms with that.’

- Henry Reynolds interview with Philip Adams on Late Night Live. 9th Feb 2021 here from 12:00.

Now, as ‘we’ understand it, Professor Reynolds has only relied upon the written records - the archives of colonial newspapers, journals, memoirs, photographs and government and anthropological reports - to come to his conclusions regarding a supposed ‘Frontier War’, with its high level of violence and killings. Perhaps he has also examined museum artifacts, visited actual, alleged massacre sites and spoken to Aboriginal people to learn of their oral-histories regarding massacres.

But it seems to us, that if the ‘Frontier Wars’ were so bloody, where are the remains of the ‘thousands’ of bodies? Where are the bone fragments and skulls showing gunshot wounds and sabre cuts? Where are the copies of police records, medical records, newspaper reports and settler journal entries describing wounded Aborigines and their treatment? Where is some corroborating physical evidence? If there is no archaeological evidence to support Bruce Pascoe’s and Henry Reynolds’ claims for the ‘Frontier Wars,’ maybe they didn’t really happen? Or maybe the conclusions of historian Keith Windschuttle are correct,

‘…the British colonization of Australia was the least violent of all of Europe’s encounters with the New World. It did not meet any organised resistance. Conflict was sporadic rather than systematic. The notion of ‘frontier war’ is fictional. The claim that the colonists committed genocide is unsupported by the historical evidence.’

So, Where is the Archaeological Evidence For Aboriginal Massacre Sites?

While researching this article we came across an academic paper that addressed this very issue. The paper’s Abstract and Conclusion only confirms what many normal, mainstream Australians, like us here at Dark Emu Exposed, are very concerned about. Namely, are our historians, archaeologists and anthropologists of today acting in good faith with regard to ‘truth-telling’? Are they really producing objective, accurate and truthful accounts of our country and our history? Or are they acting in ‘bad-faith’ by being very selective, or even manipulating the facts, when they publish their narratives that Australia’s history was one of a violent ‘Frontier War’ in which very many thousands of Aboriginal people were supposedly massacred?

The paper is by, Litster, M., and Wallis, L., Looking for the proverbial needle? - The archaeology of Australian colonial frontier massacres (Archaeol. Oceania 46 (2011) 105–117). The Abstract and Conclusion are as follows [with our emphasis]:

The Abstract : ‘Amongst other issues, the ‘History Wars’ raise the question as to whether or not sites of conflict on the Australian colonial frontier will be preserved in the archaeological record. We explore this question through a consideration of what the expected nature of any such evidence might be, based on general and specific historical accounts and an understanding of site formation processes. Although limited success has been achieved to date in locating definitive evidence for such sites in Australia, we conclude that there are some specific situations where archaeology could usefully be applied to give rise to a more multi-dimensional understanding of the past’.

Conclusion : ‘…building a case for the identification of a massacre site will be challenging and require multiple lines of evidence so as to be convincing. The general paucity of published information hinders attempts to systematically review archaeological investigations of massacre sites to date. And although…such studies are too risky to attempt as they ‘could ultimately fail, because even if evidence is found, it is unlikely to be of the kind that will be unequivocal’, we argue it is important to make explicit the complexities of such approaches to avoid their subsequent misuse by ‘deniers’.

By critically examining available historical accounts in combination with a consideration of taphonomic process, we can better understand what physical evidence is likely to be incorporated into the archaeological record and therefore minimise the risk that revisionists will make uninformed use of such studies…

It should be remembered that because of the factors we have outlined in this paper, massacre events are unlikely to be found through random chance, and archaeological evidence alone is unlikely to provide a line of evidence sufficiently robust to silence critics who doubt the ubiquitous nature of such violence.

We underline the importance in presenting a case adopting multiple lines of evidentiary support – a hierarchy of documentary sources, oral histories, material cultural evidence and skeletal remains themselves that may allow for a massacre location to be determined at a ‘possible’, ‘probable’ or ‘highly likely’ level.

Providing a detailed understanding of why evidence of a forensically acceptable level is unlikely to be preserved archaeologically may persuade some critics to accept a lower threshold for evidence of a massacre than would be required in a contemporary legal setting. Of course there will be many instances where the archaeological evidence may be lacking entirely, though given an understanding of site formation processes as we have outlined in this paper, any such absences of evidence cannot be taken as support for proving a massacre did not occur.’’

- See full paper here

The tone of this Conclusion suggests to us that the authors are advising researchers to present as much documentary, oral history and cultural (whatever that is?) ‘evidence’ as possible to ‘puff-up’ their case because the real, hard, archaeological evidence is probably non-existent. This sounds like alien UFO research - there is no end of documentary, oral, cultural (fuzzy film footage) ‘evidence’ available. But we still haven’t been shown an actual UFO, principally because we would suggest….there are no UFO’s - their existence is just made-up.

Presumably also, we here at Dark Emu Exposed would be regarded, as the paper describes, as ‘deniers’, merely for asking the question, ‘Ok, so you claim that there were 20,000 Aboriginal Australians killed or massacred in the Frontier Wars. Is there any physical evidence, such as the victim’s skulls and bones with sabre cut markings, or bullet holes?’

Are we not even entitled to be labelled as ‘skeptics’ rather than be branded outright ‘denier's’?

We here at Dark Emu Exposed actually have an open mind and agree that there is a considerable amount in the historical record to show that killings and some massacres of Aboriginal people did occur. However, without a convincing amount of confirmatory physical and archaeological proof, we are still very ‘skeptical’ that the so-called ‘Frontier Wars’ were anything other than sporadic, uncoordinated clashes. There has not, as yet, been made available enough evidence to say that there was actually a ‘Frontier War'.

What Evidence Do We Have So Far in Support of the Frontier War Theory?

The Historical Aboriginal Massacre Records

Professor Lyndall Ryan with the map of the Colonial Frontier Massacres (c) Rolla Films

Professor Lyndall Ryan, of The University of Newcastle, has published a Colonial Frontier Massacre Map. This covers her definition of ‘massacres’ in Australia from 1788 to 1930 and is designed to provide a national picture of the extent of Aboriginal and settler violence.

Professor Ryan’s map is here, but even though it cost some A$1million to produce, it is rather ‘clunky’ to use so, for our purposes, we find the ‘slicker’ exact copy that has been reproduced by The Guardian here to be more convenient to use.

The Guardian tells us that,

‘The massacre map now details about 250 massacres that meet strict criteria of standards of proof (Note 1), covering every state except Western Australia. The estimated death toll from those incidents is about 6,200 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and fewer than 100 colonists, with an average of 25 Indigenous people killed in every massacre. The map of the massacres of Indigenous people reveals an untold history of Australia, painted in blood. The lead researcher, Prof Lyndall Ryan, said that she believed the updated map only listed about half of the massacres that took place on the Australian frontier, and that the real figure was closer to 500.’

The Guardian Headlines :

Forced to build their own pyres: dozens more Aboriginal massacres revealed in Killing Times research.

The Pinjarra massacre: it's time to speak the truth of this terrible slaughter - Though it’s portrayed by some as a battle, the overwhelming evidence can leave no doubt as to the nature of these extrajudicial killings.

Blood, brains and foul murder: evidence of Australia's massacres is in its newspapers The frontier massacres were very public murders – known about, sometimes complained about – but the killings went on.

So the historians have been very busy detailing the recorded instances of large-scale killings of Aboriginal people and a sympathetic media is keen to promote the narrative of the very violent ‘Frontier War.’

Based on the Professor Ryan’s data showing 6,200 Aboriginal deaths (Note 2) and her comments that she thinks she has collated only about half the massacres that occurred, then her potential total massacre death toll is say, 2 x 6,200 = 12,400. To this figure needs to be added all the Aborignal, non-massacre killings, that is, when the incident’s death toll was less than six. Let’s guess this to be say, 8,000 Aboriginal people killed, which then brings the total death toll to around 20,000 which is about what historian Henry Reynolds is claiming.

Note 1: Our initial work so far on Professor Ryan’s and The Guardian’s Map has located a number of errors and we would suggest that some entries fail to pass the so-called ‘strict criteria of standards of proof.’ We have a blog-post on this topic in progress and will post in the future. We are also wary of any work the Professor Ryan does that involves the handling of numbers after she told Helen Dalley in an interview on Nine’s Sunday program in 2003, “Ryan replied: "Historians are always making up figures."

Note 2: Professor Ryan’s argument is that her documented Aboriginal death toll of 6,200 (so far) is evidence that a state of ‘Frontier Warfare’ existed between the ‘opponents’ - the Aborigines and the settlers. However, if she wants us to accept this, then wouldn’t it be justified to claim that ‘Warfare’ was endemic in Aboriginal society anyway given that a crude tally of the recorded inter-tribal killings for the 120 years between 1803 and 1923 comes to 3433 by our calculations? (See here). And that is just the tally of inter-tribal deaths that were recorded where settlers were living amongst Aboriginal peoples. For the rest of Aboriginal Australia, far ahead of the frontier and away from the settlers and their note-pads, the inter-tribal death toll might have been truely horrific.

So maybe Aboriginal ‘Non-Frontier Warfare’ was about as deadly as colonial ‘Frontier Warfare.’ Perhaps for Aboriginal people there was not much of a change at all in the annual death tolls pre- or post-colonisation - the only change being the skin colour of their opponents.

Indeed, by a perverse fluke, Reynolds’ death toll of 20,000 in northern Australia is say, 10% of the total Aboriginal population in the north, which accords well with the actual observations of anthropologists such as Lloyd Warner, and estimates by historian Geoffrey Blainey, on the death tolls of inter-tribal warfare in pre-contact Aboriginal societies [references to come in a future blog-post-Ed.].

Is there Illustrative Evidence for Aboriginal Killings and Massacres?

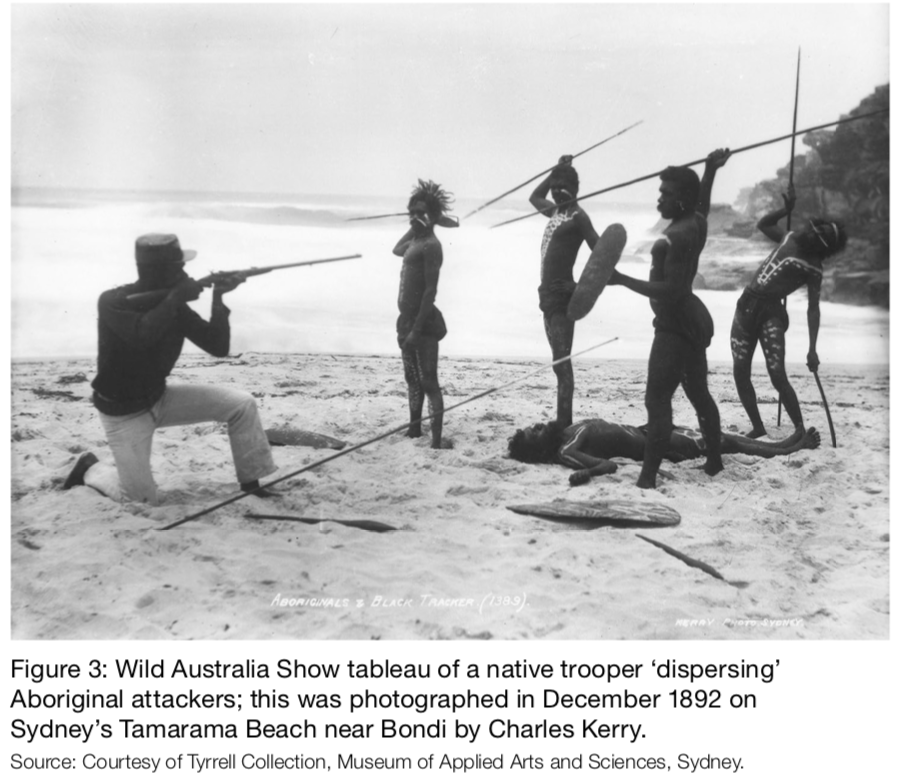

There are quite a few ‘artistic’ representative illustrations of Aboriginal killings that were published in colonial times. For example, Figures 1 to 4 below were published as being based on ‘real’ events, but it is very difficult to know how accurate they are especially with regard to the number of Aboriginal casualties. In general, these illustrations are not made by eye-witness artists, or even related by an eye-witness to the artist. Rather, they are compositions by an artist imagining what the incident would have looked like, if indeed it even occurred.

It is not our position here to deny that the practice of what was euphemistically called, ‘dispersing the blacks’ (ie: the killing and massacre of Aboriginal people) did actually occur in parts of northern Australia. What we are concerned with is determining whether it was a full-on bloody ‘Frontier War’ or instead, a series of sporadic clashes and skirmishes principally involved with property (stock, stores, women) theft and/or resources competition for waterholes, hunting grounds and grazing lands.

Fig. 1 - This is said to be, ‘Mounted Police and Blacks' depicts the massacre of Aboriginal people at Waterloo Creek by British troops. Tinted lithograph Held at Australian War Memorial - Source

Fig. 2 - An illustration from the large folio, ‘A Picturesque Atlas of Australiasia, Vol II, p340.’ This depicts the supposedly widely known practice of what was euphemistically called, ‘dispersing the blacks’ (ie: the killing and massacre of Aboriginal people)

Fig. 4 - A drawing from the book by Norwegian scientist, Carl Lumholtz, 'Among Cannibals’, 1889, p383. There is a large backstory to this illustration which we will describe in a future post. Suffice to say here that it is a contemporary illustration of the views of some that there were indiscriminate killings of ‘blacks’ in Qld by the Native Police.

Illustrations by ‘Eye-witnesses’

It is possible to locate a very few illustrations by ‘eye-witnesses’ who were on the frontier in the time when the bloody, raging “Frontier Wars’ were meant to be underway. Figure 5 below is a pencil drawing form 1843 which we understand was by Thomas Taylor, who was either an eye-witness himself, or was close enough to an informant to be able to accurately depict this incidence of a ‘dispersal’. But one sketch doesn’t make a ‘war.’

The other sketch, is by Aboriginal artist Tommy McRae who was born ‘on the frontier’ in southern Australia. He was a relatively prolific artist who left many drawings of Aboriginal life on the frontier and how it interacted with the settler wave sweeping his ancestral lands. Despite McRae leaving many depictions of inter-tribal violence like Figure 6 below, we have been unable to locate even one where MacRae shows settler-Aboriginal violence, as would be expected during a sustained ‘Frontier War.’ Obviously in his part of the country there was presumably no “Frontier War”.

Fig. 5 - Pencil drawing by Thomas J. Domville Taylor (1817-1889) of ‘Squatters attack on an Aboriginal camp, One Tree Hill, Queensland, 1843’ (Source National Library Aust)

Fig. 6 - Aboriginal man Tommy McRae (c.1835–1901) was an Aboriginal artist who lived on the ‘frontier’ in the Upper Murray district of Australia. He recorded a number of inter-tribal fights or ‘wars’ such as the above. He did not depict even one ‘massacre’ or ‘Frontier War’ between Aboriginal people and settlers as far as we can ascertain.

Is there Photographic Evidence of Massacres & Killings?

Figure 7. - Photograph of adventurer Julius Popper posing over a dead Selk'nam (an indigenous people in the Patagonian region of southern Argentina and Chile, including the Tierra del Fuego) killed during a fight in 1886. Source : Photographer unknown : Photo album donated to then-president Miguel Juárez Celman. The picture is available at The Museum of World Cutlure (Världskulturmuseet) as no 008218. Julius Popper during one of his Indian hunts. A naked aboriginal, murdered by his militiamen, at Popper's feet.

As far as we have we can find, there are no photographs of actual killings or massacres of Aboriginal people. This is surprising, given that one would expect that if there was a genuine ‘Frontier War’ raging across colonial Australia, photographers would have been in the ‘thick-of-it’ with their new recording medium.

In other parts of the world, at about the same time as when we are led to believe a bloody ‘Frontier War’ was raging across northern Australia, some photography does indeed exist showing the results of a genuine bloody encounter between an indigenous hunter-gatherer people and European settlers and their agents.

For example, in the late 19th century in Patagonia and Terra del Fuego in South America, Julius Popper, a Romanian Jew, received in 1886 a permit from the Argentine Government to form an exploration company to mine for gold. He led an 18-man expedition into Patagonia, where he and his men were allegedly attacked by eighty Selk'nam warriors armed with bows. The adventurers responded by firing their Winchester rifles, killing all but two of the Selk'nam. After the fight, Popper "posed his men in the attitude of troops repelling a charge, took a position himself astride one of the dead Indians, and then had the outfit photographed for subsequent use." Source Wikipedia.

As far as we have been able to ascertain, there are no such gruesome ‘trophy’ photographs depicting successful ‘dispersion’ raids on Australia’s frontier, despite the claim that there were hundreds of massacres and thousands of Aboriginal people killed. At this time a number of photographers, such as Paul Foelsche (1870s) and John Lindt (1870s) amongst others, were active in photography in northern Australia. Why didn’t they leave a record of some of the ‘bloody battles’ from the ‘Frontier Wars’? Maybe because there weren’t any ‘wars’ to photograph?

Figure 8 - Aboriginal (?) skulls and bones in a cave in central- west Queensland.

The closest photograph we have been able to locate of what may be an indication of an Aboriginal massacre is the photograph of a pile of skulls and bones that is said to have been published in the 1933 book by Hudson Fysh, Taming the North. (Angus & Robertson).

Cairns based historian, Timothy Bottoms says of this photograph of a pile of skulls and bones,

‘Hudson Fysh identified these skulls and skeletal remains as ‘A Native Burial Place’ in his ‘Taming the North’ (1933, first ed., p162 but was deleted from later editions). No Aboriginal mortuary practices in the region of Alexander Kennedy’s stations buried their dead in this manner, so it appears to have been done by a white man. To local Cloncurry district Aboriginals it would have been sacrilege to pile skulls in this way'.’

- Bottoms, T., Conspiracy of Silence - Queenslands frontier killing times, Allen z& Unwin, 2013, plate 21.

So maybe this photograph represents hard evidence of a massacre during the ‘Frontier Wars’; but then again it would appear to us to be inconclusive as there is no way of knowing. Maybe someone has gathered these bones from several, differently aged, grave sites; maybe they are murdered white settlers or Chinese ‘over-landers’ who perished on the way to the Palmer River gold-fields? And then these fourteen skulls don’t add up to Henry Reynolds’ ‘Frontier War’ death toll of 20,000.

Figure 9 - Photograph of ‘War” dead on an American civil War battlefield (1860s) - why are there no equivalent photographs from Henry Reynold’s ‘Frontier Wars’ in Australia?

Figure 10 - ZULU WAR Isandlwana Battlefield of 1879 shortly after the famous battle showing abandoned supply wagons. Reference - why are there no equivalent photographs from Henry Reynold’s ‘Frontier Wars’ in Australia?

Further Evidence of Henry Reynolds’ ‘Word-Creep’ - changing ‘Frontier Clashes’ to ‘Frontier Wars’

To our mind, looking at how colonial settler governments responded to their indigenous populations provides further evidence to support Keith Windschuttle’s view that,

…the British colonization of Australia was the least violent of all of Europe’s encounters with the New World. It did not meet any organised resistance. Conflict was sporadic rather than systematic. The notion of ‘frontier war’ is fictional. The claim that the colonists committed genocide is unsupported by the historical evidence.’

The images below describe how each of the colonial settler governments of the United Sates, New Zealand and Australia (Van Dieman’s Land) officially dealt with conflict between the settlers and the indigenous population. The United States undertook a series of officially declared ‘wars’ with certain groups of American Indians (but not all tribes). The defeated Indian enemies were treated as virtual ‘war criminals’ and often executed, most notably in the hanging of the Dakota 38 in 1862.

In the New Zealand Wars, which took place from 1845 to 1872, the New Zealand Colonial government and allied Māori on one side fought with Māori and Māori-allied settlers on the other. They were previously commonly referred to as the Land Wars or the Māori Wars and often consisted of pitched battles against strongly defended and fortified Maori Pa, or defensive settlements. No ‘battles’ or ‘wars’ of this scale and complexity ever occurred between Aboriginal and settlers or government forces in our Australian colonial history.

How the colonial governments of Australia officially treated violence between the Aborigines and the settlers is perfectly illustrated in The Proclamation Board (Figure 13 below). Aboriginal people were not regarded as enemies. They were regarded as British subjects and, as far as was practicable, the legal ‘equal’ of the settlers. The government’s position was that you cannot legally be at ‘war’ with your own subjects - you can have violent ‘clashes’, skirmishes, murders and plunder, but the transgressors (either Aboriginal or settler) are not ‘war criminals’. They were criminals and needed to be dealt with via the criminal justice system, not military tribunals.

This is one of the main reasons why, although Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islanders are recognised at the National War Memorial as members of Australia’s Military forces, on an equal footing with all other servicemen and woman, there is no formal memorial to recognise any so-called ‘Frontier War’ between Aboriginal people and the first colonists and settlers. There was no ‘war’ as we legally and historically understand the meaning of that word.

So once again, there appears to be a lack of physical evidence to support Henry Reynolds ‘Frontier war’ theory.

Figure 11 - The Dakota War of 1862, also known as the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862, or Little Crow's War, was an armed conflict between the United States and several bands of Dakota (also known as the eastern Sioux). After the war ended with the defeat of the Dakota and a trial by a military court, 38 Dakota men were hanged on December 26, 1862, in Mankato, Minnesota. This was the largest one-day mass execution in American history. - Source Wikipedia

Figure 12 - THE 1863 ASSAULT ON RANGIRIRI During the Maori Wars BY THOMAS REDMAYNE. COURTESY OF ALEXANDER TURNBULL LIBRARY - Source

The New Zealand Wars took place from 1845 to 1872 between the New Zealand Colonial government and allied Māori on one side and Māori and Māori-allied settlers on the other. They were previously commonly referred to as the Land Wars or the Māori Wars. At the peak of hostilities in the 1860s, 18,000 British troops, supported by artillery, cavalry and local militia, battled about 4,000 Māori warriors.

The Māori were able to withstand the British with techniques that included anti-artillery bunkers and the use of carefully placed pā, or fortified villages, that allowed them to block their enemy's advance and often inflict heavy losses, yet quickly abandon their positions without significant loss. - Source Wikipedia

Figure 13 - The Proclamation Board of Governor George Arthur (1784-1854) to the Aborigines. The Board presents a four-strip pictogram that attempts to explain the idea of equality under the law. Those who committed violent crimes, in Van Diemen’s Land, be they Aboriginal Australian or European settler, would be punished in the same way. - Source

Is there Archaeological Evidence of Killings and Massacres - Bullet Wounds and Sabre Cuts in Bones?

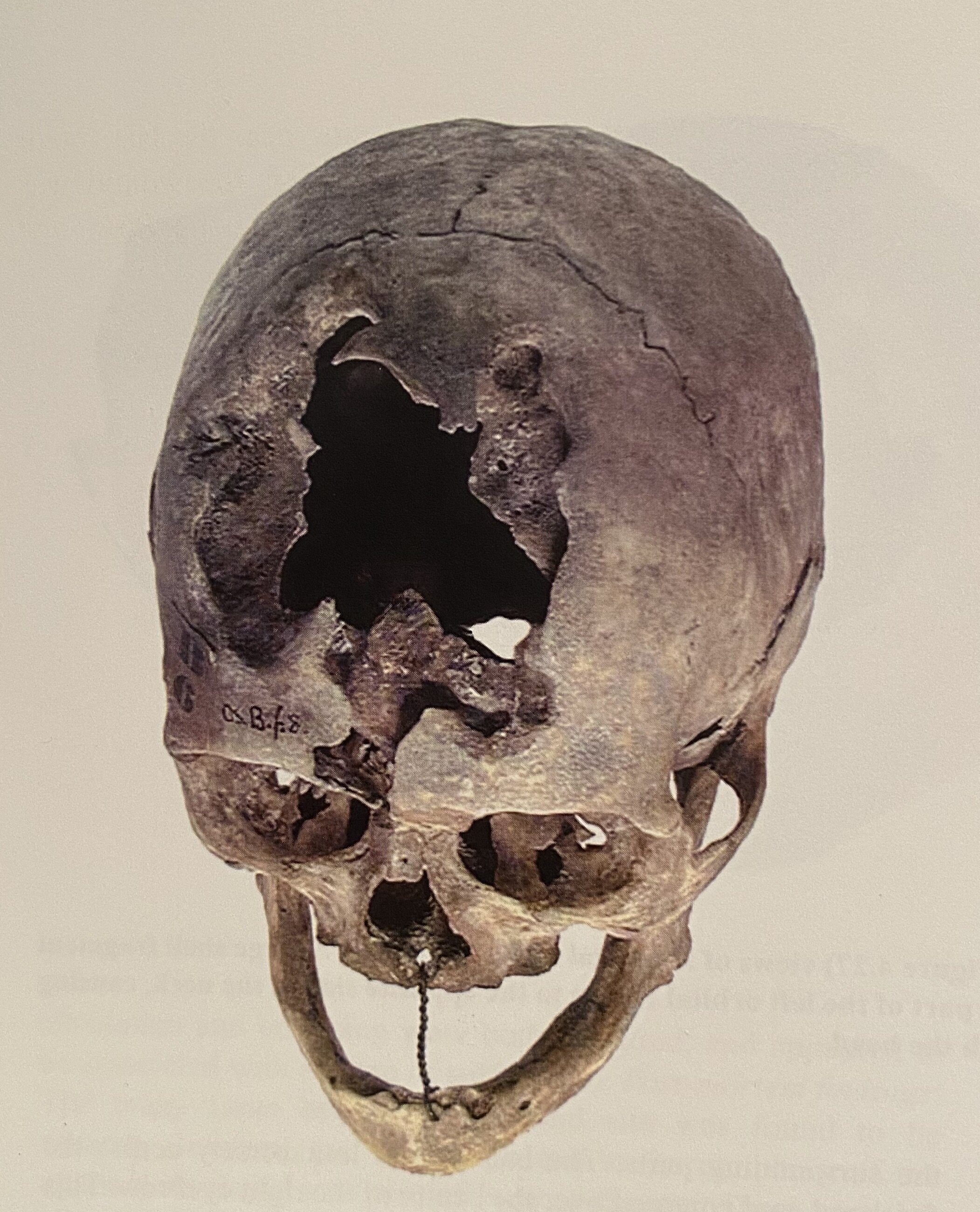

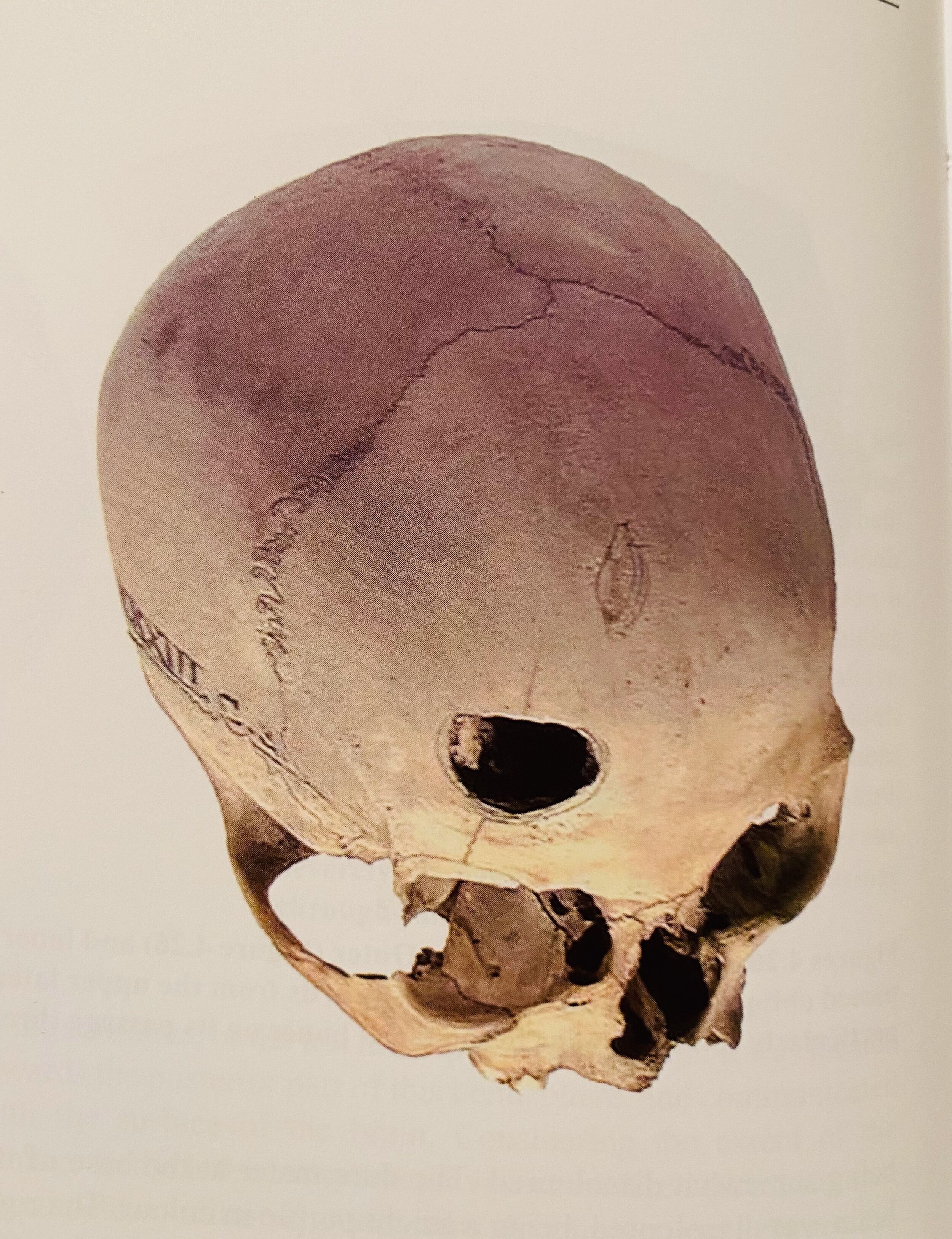

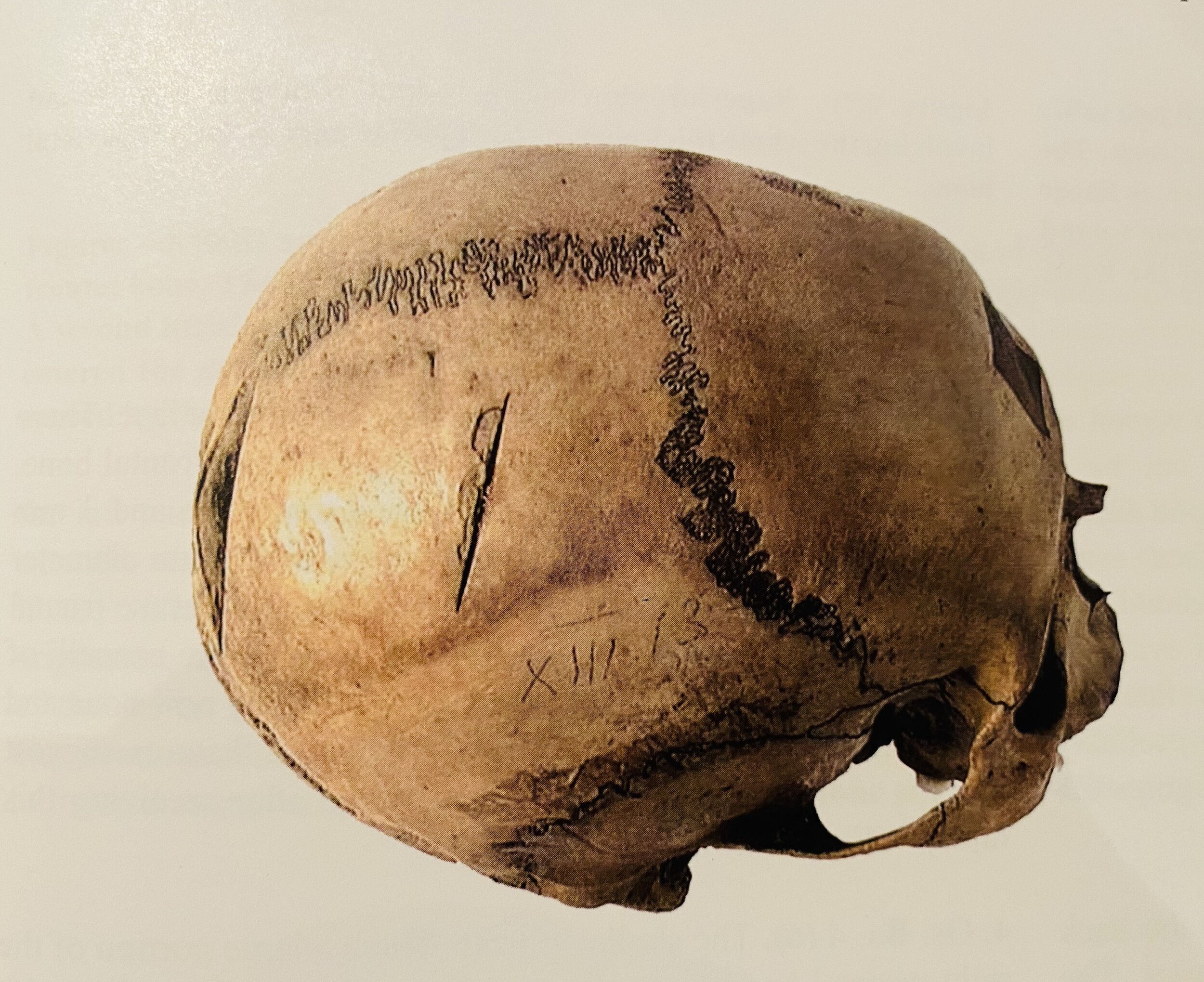

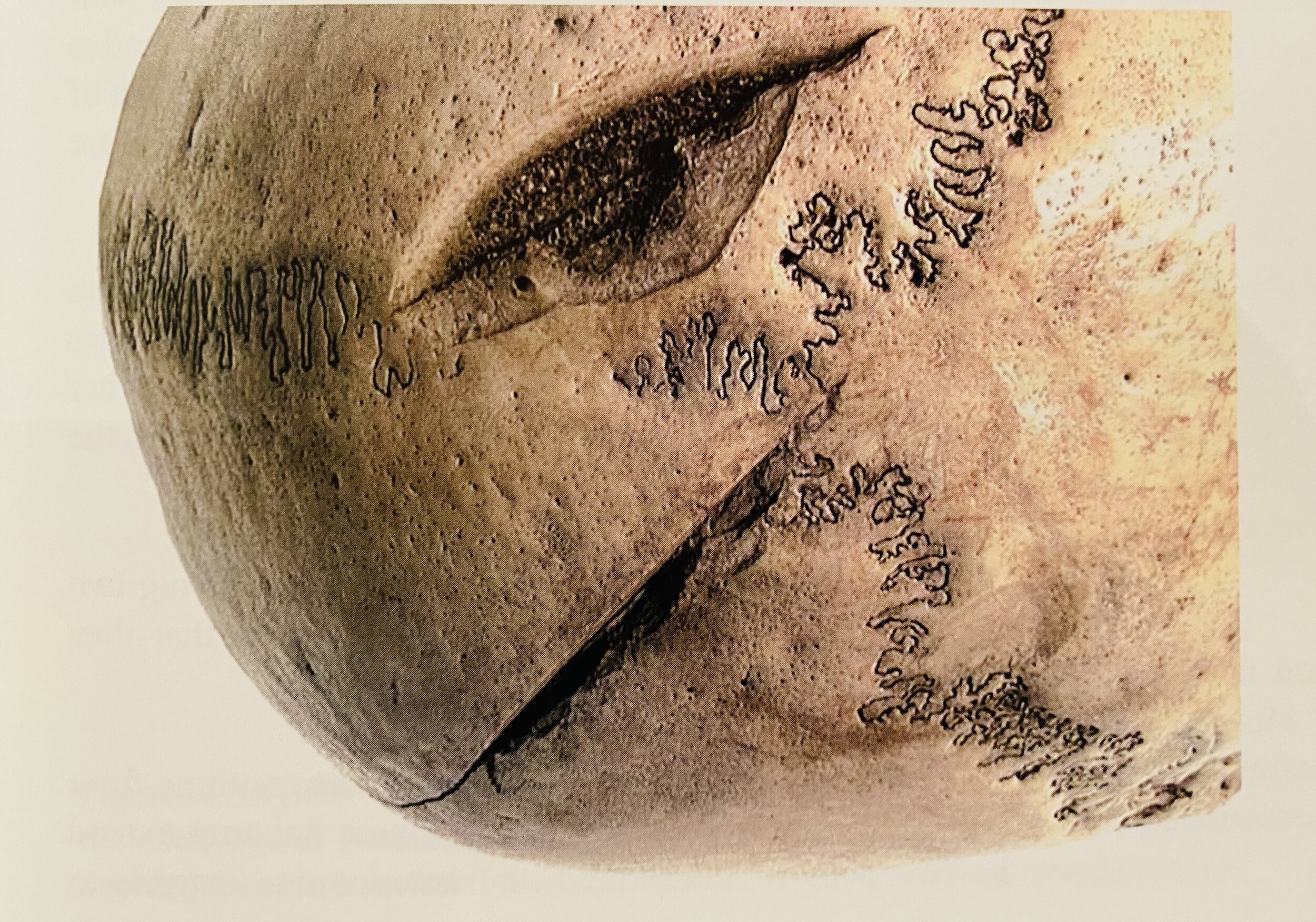

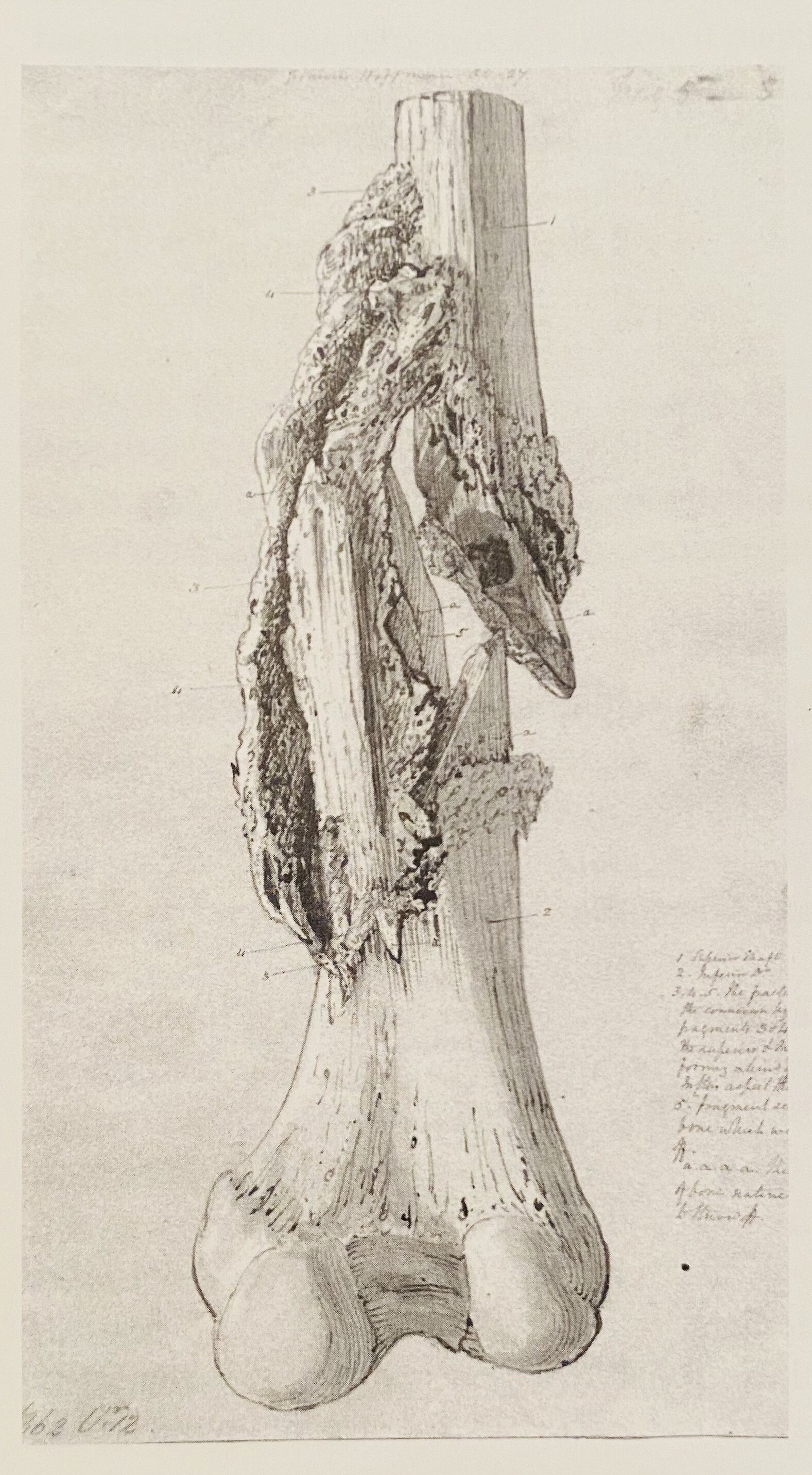

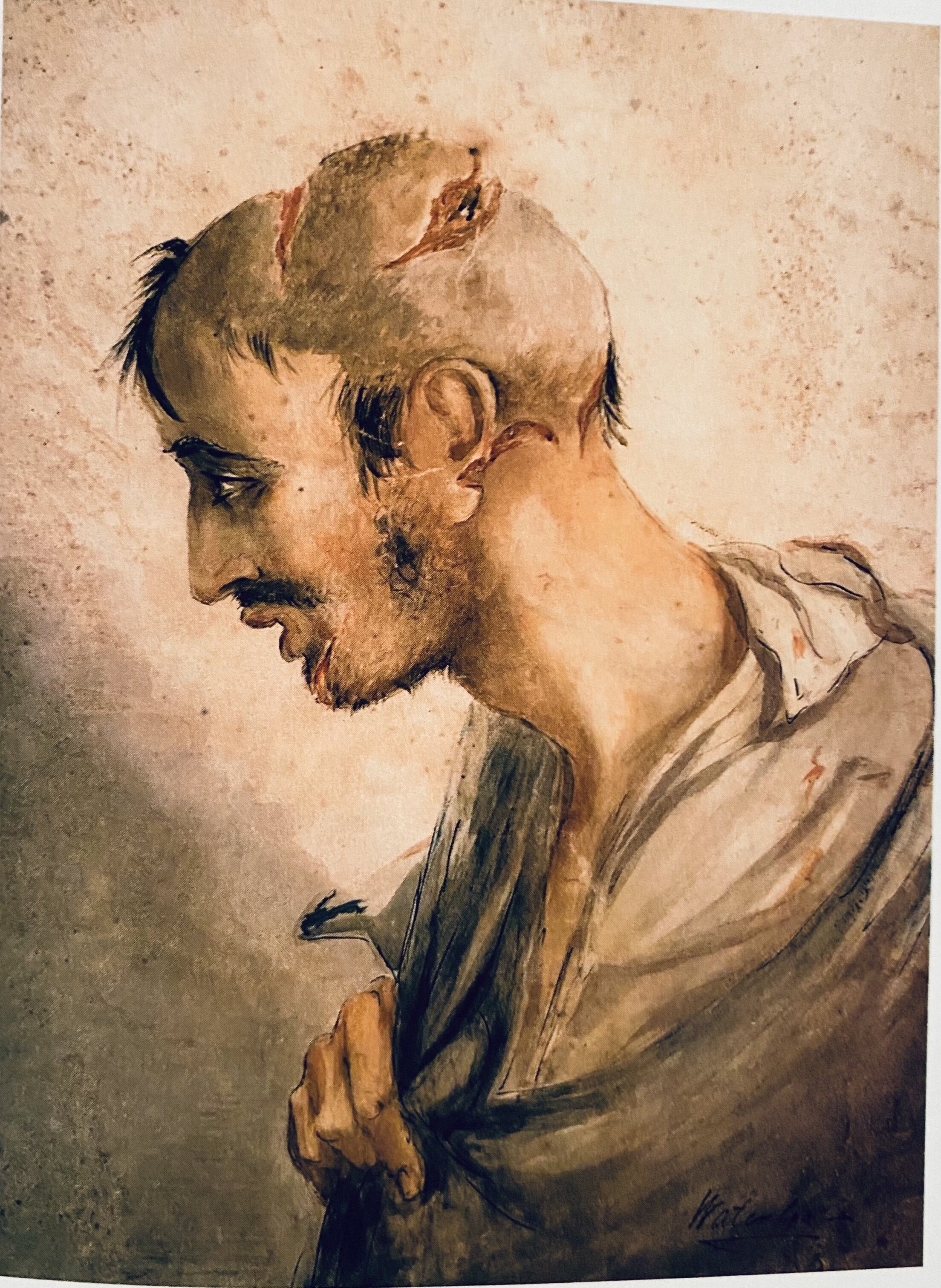

The Illustrations below are from the book, Musket-ball and Sabre Injuries from the First Half of the Nineteenth Century (Kaufman, M., Royal College of Surgeons, Edinburgh, 2003) and graphically illustrate the damage done to victim’s bones by musket shots and sabre cuts.

Now, it seems a fair question to ask,

‘If there was, as Henry Reynolds claims, a bloody ‘Frontier War ‘going on for some 80 years in colonial Australia where 20,000 Aboriginal people died, wouldn’t one expect to find at least some archaeological evidence of the victim’s skeletons, skulls and bones showing musket and rifle bullet wounds and sabre cuts?’

And indeed, wouldn’t wounded survivors have gone on to live for a period of time, perhaps years, after their attack and wouldn’t their fate have been recorded in journals, mission, medical or police records?

Incredibly, Fig. 1 below is of a skull showing extensive ulceration of the frontal bone from a gunshot received at Waterloo. The patient, a field officer in the army, survived for many years after receiving this injury, but had repeated bouts of epileptic fits. The lack of many of his teeth confirms that he lived to a very old age. Why don’t we seem to find any records of Aboriginal people wounded like this? If Reynolds says 20,000 Aboriginal people were killed, there must have been this number again, if not very many more, who were wounded to various degrees, but survived by fleeing.

The following images are of wounds that were incurred in the battle of Waterloo, and subsequently treated at the British Military Hospital in Brussels, in June 1815.

To give the reader some indication of the complications and inevitable pain and suffering caused by these wounds, we have included the clinical case notes for some of the above Figures:

Fig. 3. John Gibson - an artillery-man, aged 23. Gunshot wound-induced compound fracture of the tibia. He was wounded on 28 May, the skin being grazed by a ball. He progressed well throughout July, but the wound site assumed the character of an ulcer. On 30 August, the wound site appeared very unhealthy, although during the early part of September, there was a general improvement in his condition. By 25 October, a large portion of the lateral part of the tibia appeared to be exfoliating, and the surrounding tissues appeared unhealthy. Shortly afterwards, part of the exfoliated bone was exposed, and a probe could be passed a considerable distance in all directions over the diseased bone. Two other fistulous apertures appeared in the overlying skin, and a considerable discharge of pus came from one of these openings, running in the direction of the popliteal fossa. By 7 November, bone was now exfoliating through the wound site. On 23 November, it was necessary for the wound to be enlarged both upwards and downwards in an attempt to remove the sequestered bony fragments that had become loose - but these could not be removed. On 8 January, a large sequestrum of bone was removed from the wound after the latter had been enlarged again - the bony fragment was about two by one and a half inches in size, and consisted of most of the anterior surface of the tibia. On 23 January, he was feverish, but sent for convalescence. On 6 March, he had to be re-admitted because of a profuse foetid discharge from the leg wound,and the exfoliation and discharge of more bony fragments from the bottom of the wound site. His general condition was poor. By 15 March, his general condition improved, and this continued. During the early part of April, he had a poor appetite and suffered from lack of sleep. By 7 April, he was feeling much better, coughing less and his appetite had improved. After almost a year in hospital, on 13 May, he was eventually sent to Santander for convalescence. While this would appear to be an amputation preparation, no information is available in the clinical notes to indicate when this preparation might have been obtained.

Fig 6. George Cusack, aged 36. Clinical case history: Penetrating gunshot wound of the thorax, fracturing the 11* rib, with the ball lodging in the body of the last dorsal (i.e. thoracic) vertebra. He died on the 11 th day after receiving this injury. A musket-ball entered the chest about three inches to the left of the spinous process, at the edge of the 9th-11t ribs on the right side. It fractured the neck and angle of the 11* rib and lodged in the angle of the last dorsal (i.e. thoracic) vertebra. The external wound was about the size of a half-crown. On admission to hospital, he had difficulty in breathing and acute pricking pains in his ankles and feet. He was bled 20 ounces, and given several doses of an antimonial mixture of opium. On the 2nd day, he was delirious and the pain in his feet continued intermittently to the last. On the 3rd day, 20 ounces of blood were again withdrawn from the arm, to good effect, and he was both quieter and less confused. He had retention of urine, and this was relieved when a catheter was passed. During the night, he was hot and feverish. During the succeeding days, he had intermittent bouts of restlessness and was also delirious. On the 10 day, he had difficulty in opening his mouth, and from about 4 o'clock in the morning had complete trismus. He also had occasional bouts of opisthotonus. He died on the following day. Post-mortem findings: the entry site was next to the spinal canal, and projected a little into it, the ball having perforated the right lung during its passage. This lung was found to be adherent to the wound site, and yellow turbid serum was found in this region. When the lungs were infated with a bellows, air could be heard escaping from a minute opening, although its exact location could not be discovered. The head of the 12* rib was dislocated onto the body of the succeeding vertebral body. The diaphragm was torn near the 12* thoracic vertebra, and there was superficial ulceration of the liver and kidney, probably caused by the passage of the ball. The spinal cord was ruptured and portions of the fractured spongy bone had passed inwards into it. These bony fragments were found entangled within the substance of the spinal cord. The coverings of the cord were infamed below the level of the lesion. The brain was healthy, but a considerable effusion of serum was found around the base of the brain. Yellowish lymph-like fluid surrounded the damaged spinal cord, and extended distally as far as the cauda equina.

Figure 10. - Soldier of the 1st Dragoon with a head sabre cut: “a portion of the skull at the vertex is completely detached by the sabre cut. The soldier could not speak and stooped languidly with a vacant and indifferent expression of countenance.”

Why Don’t we Find the Remains of Buried Aboriginal Massacre Victims?

On rare occasions even today, a casualty of the battle of Waterloo in 1815, 200years ago, has been discovered, with the fatal musket-ball still clearly visible in his skeleton. Why don’t we find buried Aboriginal massacre victims like this, many of which we are told were killed only 100 years ago?

The 200-year-old skeleton found under a car park on the site of the Battle of Waterloo has been identified as a Hanoverian with a hunchback, fighting to liberate his homeland from Napoleonic occupation.

Military historian Gareth Glover believes the soldier to be Friedrich Brandt, 23, a private in the King’s German Legion of George III, who was killed by a musket ball that was still lodged between his ribs when he was found in 2012.

The soldier was unearthed in 2012 when a mechanical digger excavated an overspill car park near the Lion’s Mound, a well-known area to those who have visited the historic battleground south of Brussels.

The only references we can find of Aboriginal remains that may contain bullet wounds are those that are (were - some 1,600 have been returned to Australia) in museum collections, some of which were said to contain ‘bullet holes” (Tuniz, C, et al , The Bone Readers, Allen & Unwin 2009 p206). Other large collections of skeletal remains, such as the Murray Black Collection of more than 1,600 skeletons that were exhumed from burial mounds along the Murray River in the 1930s and 1940s may have wounds caused by the ‘raging’ “Frontier War”. But then again maybe not. Given the general inability for researchers nowadays to scientifically examine Aboriginal remains, it is most likely we will never know.

But Maybe we Have Found a Victim ?

In 2012 a skeleton of an Aboriginal man was discovered with a long gash in its skull. The bones were found eroding out of a riverbank in New South Wales' Toorale National Park. The skeleton — a male, likely between 25 and 35 years old when he died —was well preserved and appeared to have been carefully buried in a tightly flexed position. He was nicknamed ‘Toorale man’.

Maybe finally here was the ‘smoking gun’ - archaeological proof of the violent ‘Frontier Wars.’ The first researchers on the scene certainly thought so when they reported,

‘An Aboriginal skeleton found on the banks of the Darling River in far north-western NSW and bearing what appear to be sword wounds is raising questions about the date of first contact with Australia’s First Peoples.

Dr Michael Westaway, an expert in Aboriginal archaeology from Griffith University’s Environmental Futures Research Institute, told the ABC’s Catalyst program that the wounds were indicative of an “aggressive and hostile attack with the intent of murder”.

State of the art science is being applied to solving the mystery of the so-called Toorale Man, whose remarkably well preserved remains were discovered in 2012 by a Baakandji tribal elder, Badger Bates, in what is now part of Toorale National Park.

Initial speculation was that the man’s death was one of thousands that occurred during frontier violence waged between Aboriginals and Europeans after white settlement. - Griffith University News.

But what is the real story? Is this just another Pascoesque beat-up to show how terrible the ‘murderous’ Colonials were?

Watch the following video to find out - and notice the ‘number-creep’ of Professor Reynolds, who now claims up to 50,000 Aborigines may have been killed in the ‘Frontier Wars’! And his very Pascoesque claim that there is no skeletal evidence because, it was destroyed by the colonials (of course it was Henry, just like when Uncle Bruce tells us, ‘the evidence of the Aboriginal farmers was destroyed by the colonials’!) [Full Catalyst film program available at ABCiview].

Hmmmm, despite the program trying to paint the killing as being a result of a ‘Frontier War’[with the obligatory dropping in of words like ‘genocide’, frontier war, violent colonials, ‘steel edged weapon’, etc] the evidence shows it was a pre-colonial killing. We can almost hear their deflated sigh of disappointment when they learn that the age of the killing is some 700 year ago. Those nasty colonials can’t be blamed, not even for supplying a steel-edged weapon to the killer Aborigines. Poor old Badger just can’t believe that his people killed his people - ‘there must be something wrong somewhere’, he says shaking his head. No support here for the violent ‘Frontier War’ theory.

So what evidence do we have so far to support Henry Reynolds’ claim that there was a violent ‘Frontier War’ during the settlement of Australia that resulted in 20,000 or more Aboriginal deaths, and presumably 20,000 to say, 40,000 wounded Aborigines? (observing that in war there tends to be significantly more wounded casualties than deaths)?

In summary we have,

historical written records - Yes, but Reynolds has not produced details of his tally of 20,000 deaths based on these records;

illustrative records (drawings, sketches, etchings, paintings, staged photographs) - Yes but only very few;

photographs of victims - None that we can find and are proven;

Aboriginal artworks and drawings - None, despite examples of inter-tribal warfare being depicted, and

Archaeological evidence of bones with bullet wounds or sabre-cuts - None so far.

One does wonder about the relatively high number of newspaper reports of killings and massacres, which don’t seem to be matched by correspondingly high numbers of physical and archaeological evidence. Perhaps there was somethimg else going on in colonial Queensland? Maybe the level of frontier violence being reported was greatly exaggerated to ‘keep the pot of racial conflict on the boil’? [and to provide ‘colonial click-bait’ so as to sell more newspapers?].

Maybe Professor Reynolds has been misled by his identification of the large number of colonial newspaper records into believing life on the frontier was a lot more violent and energetic than it really was? Some other researchers perhaps thinks so :

Cole, N., Battle Camp to Boralga: a local study of colonial war on Cape York Peninsula, 1873–1894, Aboriginal History, Vol. 28 (2004), p170

But fear not, the ‘Toy-town Academics’ are on the case to find the evidence!

For the cost of a ‘mere’ $800,000 this Flinders University project is on the hunt for the physical evidence of the ‘Frontier War.’ So let’s nip down to Bunnings and buy a shade tent and start scratching in the soil in outback Queensland and see what we can find.

Archaeologists and students excavating at the Native Mounted Police camp at Burke River in southwest Queensland. Source & Photo Andrew Schaefer.

A team of archaeology researchers dig at a site on the Cape York Peninsula - Lots of buttons and bits of crockery, but no skeletons or bullet wounded skulls or bones?

Weaponry is the 'smoking gun' - While digging at the sites, The Team discovered artefacts that further confirmed the existence of the Native Mounted Police camps.

"What we actually excavate that tells us that are things like Snider [Snider-Enfield] ordnance … things like Snider cartridges and bullets," Professor Barker said.

“Little evidence of massive bloodshed

The forces led counterattacks against the Aboriginal resistance, killing many Aboriginal people across Queensland. "We know from the documentary record that massacres and frontier violence were relatively widescale," Professor Barker said. "Throughout the 19th century whenever massacres became public, there was often an inquiry." But locating massacre sites is often difficult because of the nature of the conflict.” [ or maybe because in reality the ‘war’ was really just a series of sporadic clashes? - Editor]

Here’s the archaeologists story of the Woolgar Massacre of 1881, but where are the bodies, the bullet-ridden skulls, the broken bone fragments as evidence?

The bits and pieces unearthed by The Team to support the theory of the ‘Frontier Wars’. But no ‘real’ evidence of mass graves or skeletal remains with bullet holes and sabre cuts.

- The archaeology of the 'Secret War': The material evidence of conflict on the Queensland frontier, 1849-1901, July 2020 Queensland Archaeological Research 23:25 here

Our taxes at work - $811,000 dollars to prop up the theory that,

“Historians such as Noel Loos, Henry Reynolds, Ray Evans and Timothy Bottoms (amongst others) have demonstrated convincingly that there was substantial conflict on the colonial Queensland frontier.”

But we ask, ‘where is the real evidence’? No bodies, bullet and sabre smashed skulls and broken bones. None.

And the Team’s Conclusions?

The Bruce Pascoe Defence - The Evidence was Destroyed

"Native Mounted Police would ride through a camp, perhaps shoot two or three people and everyone would run off into the bush," Professor Barker said.

"Quite often those bodies were burned or the people would come back afterwards and traditionally inter them, so it's very unlikely that you're going find mass graves of massacred people."

The Evidence Is There We Know it, But It’s Hidden

Conclusion of the Team’s paper, Archaeology and the Teaching of Frontier Conflict in Australia, Lynley A. Wallis, Heather Burke, Noelene Cole and Bryce Barker,

‘The history of frontier conflict in Australia is at once all around us, yet at the same time still literally and figuratively hidden from view. Ongoing debates about whether what happened really constituted a ‘war’, how many people might have been affected, and whether contemporary Australia should recognise or refute such research, complicates the way we look upon the past…’

This doesn’t sound very convincing to us. Plenty of emotion that there must have been a raging ‘Frontier War’ in northern Australia, but where is the physical evidence? Professor Henry Reynolds wouldn’t be just making this up would he?