How Low Can a Writer Go in Re-writing our Colonial History?

A major theme in Mr Pascoe’s book, Dark Emu (Magabala Books, 2018 Reprint), is that pre-Colonial Aboriginal society was heavily involved in agricultural grain production (ibid., p13pp), but that,

‘it was convenient for many European settlers not to acknowledge the evidence of an Aboriginal [agricultural] economy…” (ibid., p27).

Mr Pascoe tries to support his argument, ‘that Aboriginal people…did sow, irrigate and till the land…’ by quoting, he says, the journals of the early explorer, Thomas Mitchell. In a blog post on Dark Emu Exposed, we have since shown that Mr Pascoe was wrong to draw this conclusion. In fact he was just using selective and inaccurate quoting to support this false narrative.

Mr Pascoe also produces what he says is a map of the, ‘aboriginal grain belt - after Tindale’, based on the works of the anthropologist, Dr Norman Tindale, and the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (RIRDC).

However, on fact-checking, we find that Mr Pascoe’s map is a wildly inaccurate representation, which just looks like some dodgy hand-drawn sketch to make the grasslands, where Aborigines had a high reliance on grass seeds in their diet, look much larger than Tindale and the RIRDC both said that it was.

These are two examples of errors in Dark Emu that can only be described as, ‘very concerning’. These errors potentially bring into question the whole veracity of Mr Pascoe’s argument in Dark Emu regarding Aboriginal farming and grain production.

We have now uncovered a further example, which leads us to ask the question, did Mr Pascoe really read the references he claims to have read, or is he ‘just making stuff up’?

In the Dark Emu chapter on Agriculture, Mr Pascoe claims that after reading an article by Ian Chivers, Adjunct Professor at Southern Cross University in 2012, some two years before the publication of Dark Emu, Mr Pascoe contacted Chivers to discuss, ‘how involved Aboriginal people had been with grain usage and planting’.

Mr Pascoe writes that,

‘Chivers was interested in the idea of Aboriginal grain management, but his focus had been on the economic potential for native grains in contemporary markets. A book referred to me by Chivers’ research partner Frances Shapter, ‘Australian Grasses’ by Fred Turner doesn’t mention Aboriginal people at all, but a more recent paper by Chivers argues that, ‘In Australia, we have stunning examples of long term grain food production that has no degrading impact on the environment, that did not require expensive fertilizers or pesticides, and grew without the need for irrigation water’. (ibid. p42-43).

Immediately on reading this, the warning bells started to go off in the offices of Dark Emu Exposed. This is because we just happen to know something of the life of the legendary Frederick (Fred) Turner, (1852 - 1939), F.L.S., (Fellow of the Linnean Society of London, 1892), F.R.H.S., (Fellow of the Royal Horticultural Society, London, 1888), etc.,

Let us unpack what Mr Pascoe is actually saying here and we will demonstrate how he quotes selectively, omits relevant information and indeed, 'just makes stuff up’ about our Colonial history, so as to suit his false narratives.

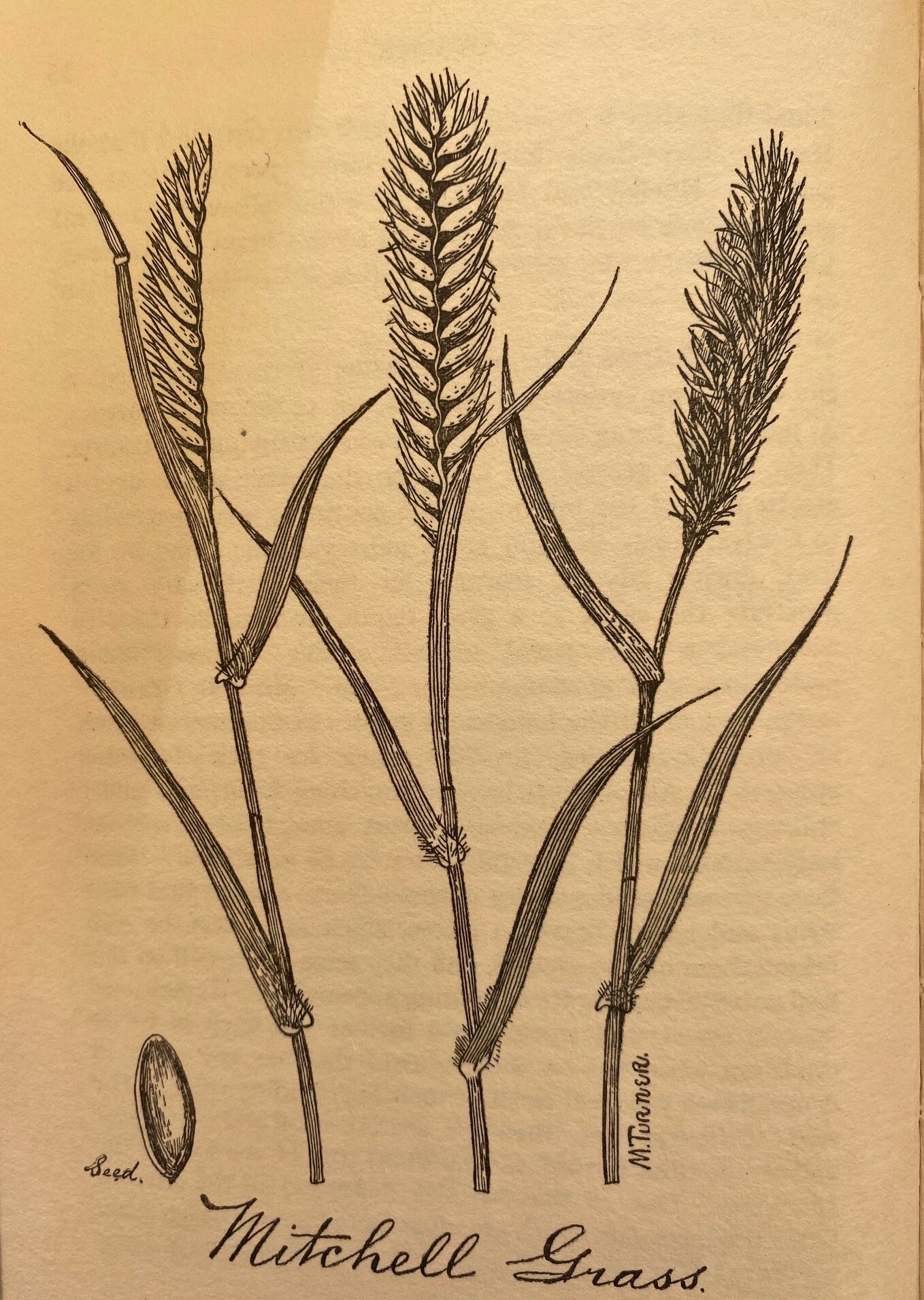

We actually have a copy of Fred Turner’s 1921 book, Australian Grasses and Pasture Plants, Published by Whitcomb & Tombs Ltd, which is similar to Turner’s 1895 edition of Australian Grasses, but has been expanded to include Pasture Plants. In addition, we accessed an online version of the 1895 Australian Grasses, less illustrations, here.

Australian Grasses & Pastures, by Fred Turner, 1921 Edition.

Mr Pascoe writes in Dark Emu that,

‘…Australian Grasses by Fred Turner doesn’t mention Aboriginal people at all’.

Well, we at Dark Emu Exposed, counted twelve times that Turner mentions ‘the aborigines’ in our 1921, expanded edition of the book.

We also counted eight times that Turner mentions ‘the aborigines’ in the online 1895 edition, when we did a word-search here.

Therefore, for Mr Pascoe to be able to write,

'‘…Fred Turner doesn’t mention Aboriginal people at all…’ [in his book Australian Grasses],

implies that Pascoe must have read the book.

So we ask, ‘what is the truth, Mr Pascoe’?

Did you read the book and see that Fred Turner, a Colonial, did mention Aboriginal people and recommended the use of their indigenous grasses (see below), but you left this out because it does not fit your narrative that the Colonials and settlers, who came after the first explorers, were either blind, or dismissive, to all things indigenous?

Or did you not even read Fred Turner’s book to see if Aboriginal people were mentioned, it being much easier, and better fitting to your narrative, for you just to say they weren’t even mentioned? In this way you and Professor Chivers look like the original leaders in discovering the benefits of indigenous grain grasses.

Either way, this is a major failing in an author who’s Dark Emu book is promoted as a Truer History to our children and actively promoted by ‘Our’ ABC.

Was Mr Pascoe Trying to Bury the Legacy of Fred Turner’s Work?

Some may say that Mr Pascoe was being dismissive of Fred Turner, the Colonial botanist and horticulturalist, who was writing about the benefits of cultivating indigenous grasses more than 100 years before Mr Pascoe’s book Dark Emu appeared, because he did not want his readership to know of Turner’s earlier writings.

Consider what Turner was writing in 1895,

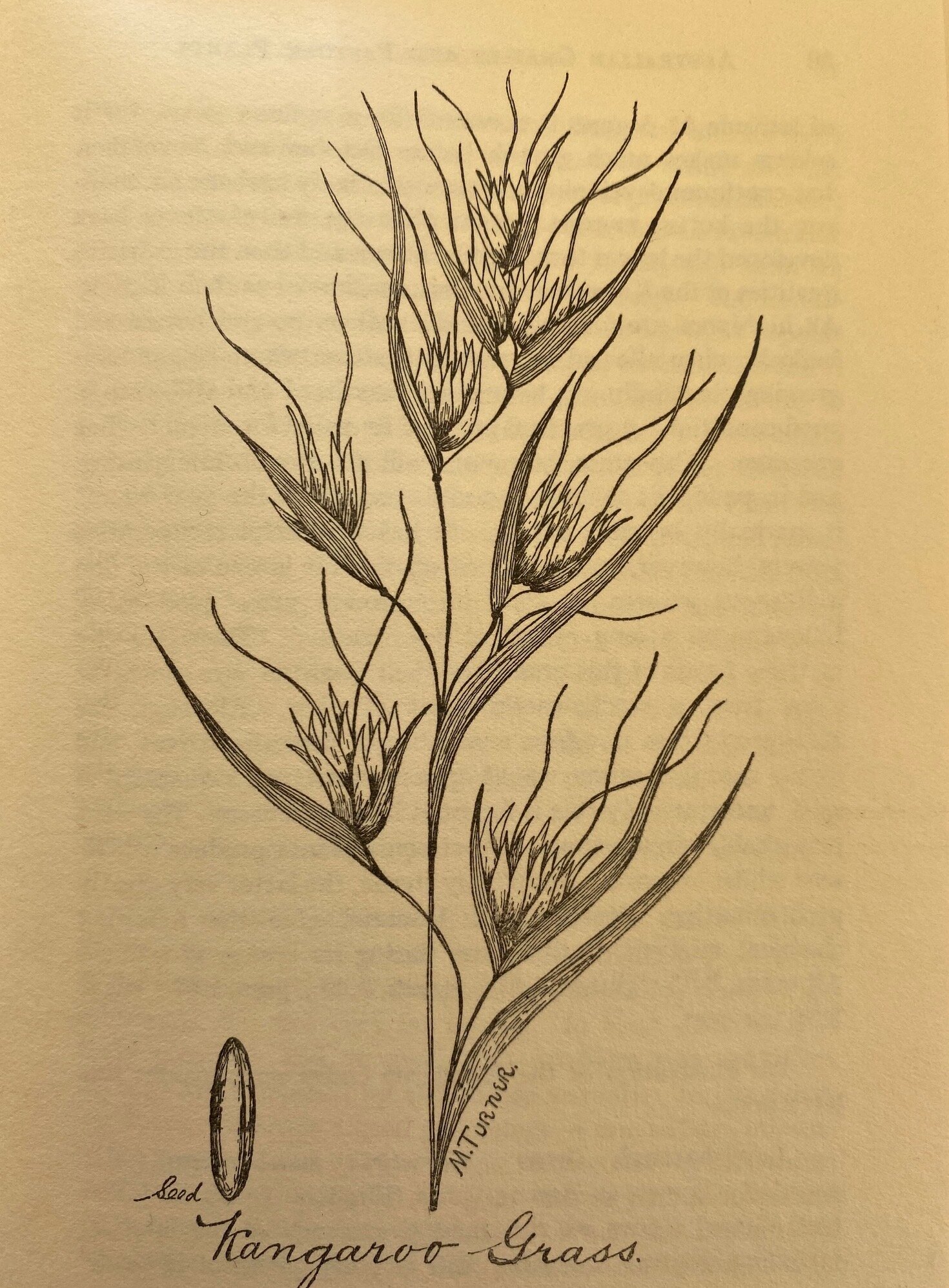

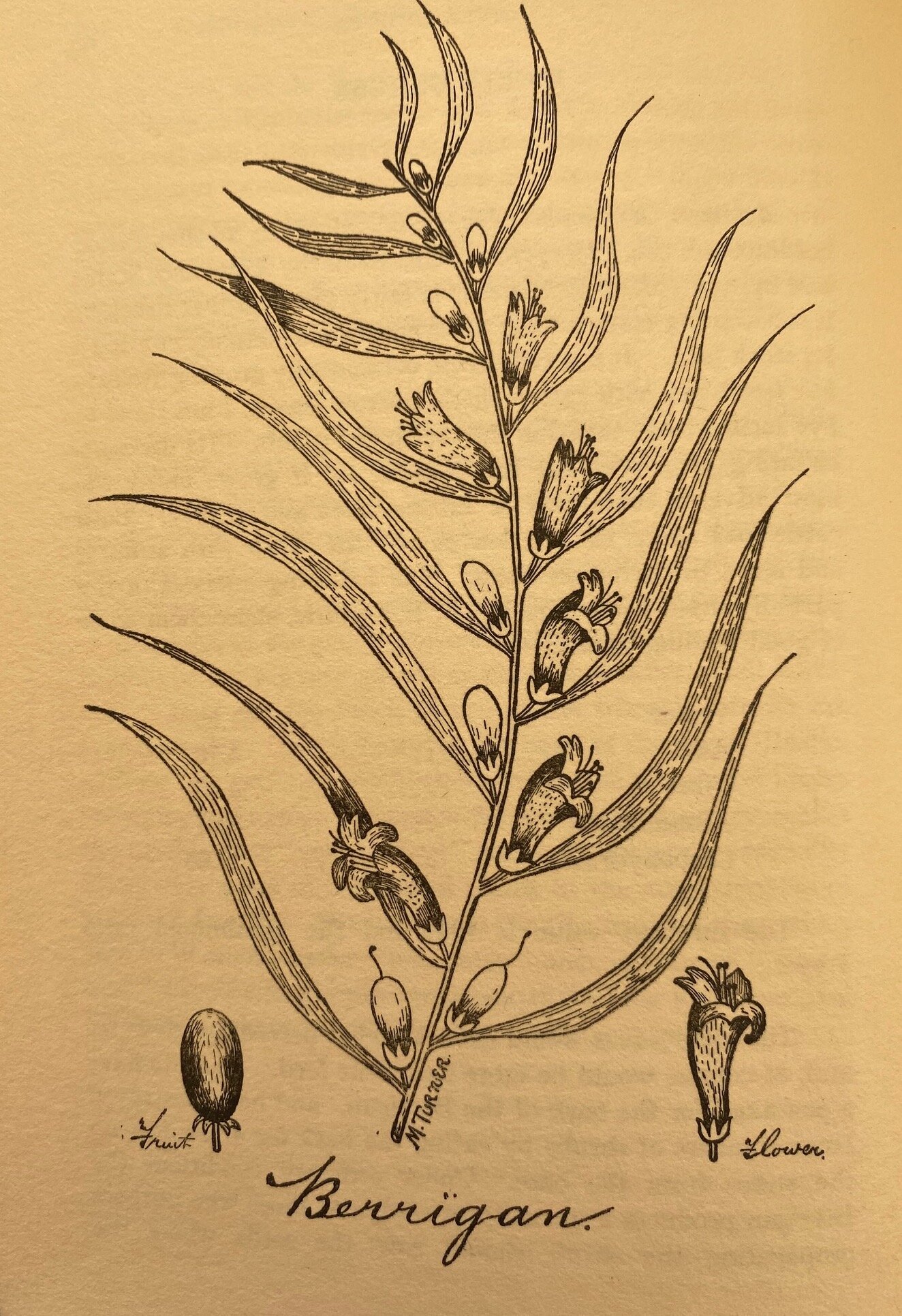

‘This valuable grass [Australian Millet, Panicum decompositum] is found all over Australia from the coastal districts to the far interior, and in some places it is very plentiful. It was collected by the Elder Exploring Expedition in Central Australia. In moist places and by the side of watercourses, I have seen this grass growing 4 feet high; on the plains, however, it rarely exceeds 2 feet in height. In all its varied forms it yields most valuable herbage which stock of all kinds are remarkably fond of, and fatten on. I have had the "Australian millet" under experimental cultivation for several years, and the amount of herbage it yielded in a few months was really astonishing. The hay that was made from it was equal to three tons per acre. I can highly recommend it for systematic cultivation either in the eastern or central portion of the continent. When allowed to grow undisturbed for a time it produces a great amount of seed…At one time the aborigines used to collect the seeds in great quantities, grind them between stones, make them into cakes, and use them as an article of food. Sir Thomas Mitchell ("Three Expeditions," vol. I. pp. 237 and 290), alluding to this grass, says : "In the neighbourhood of our camp the grass had been pulled up to a very great extent and piled in hay-ricks, so that the aspect of the desert was softened into the agreeable semblance of a hay-field. The grass had evidently been thus laid up by the natives,…we found the ricks, or hay-cocks, extending for miles,…’ - from Australian Grasses, online at section/page 36 - (our emphasis).

Not only does Turner mention the aborigines, but also the fact that they collected great quantities of the seed, and that he was also doing experiments to propagate the plants. This sounds very similar to what the ABC reported in June 2020 regarding,

‘Boonwurrung and Yuin man, Bruce Pascoe, [who] has taken a pioneering role in bringing these native grains to the dining table, with his social enterprise developing and commercialising Indigenous food, on his property at Mallacoota’.- Note 1

And if you think the Sir Thomas Mitchell quote used by Turner in 1895 looks familiar, you are not mistaken. It is the same abridged quote used by Mr Pascoe in Dark Emu! (ibid., p15).

No wonder Mr Pascoe does not want to bring the modern reader’s attention to the work of Fred Turner - Turner has been there before him!

Dark Emu has a massive bibliography of references, but one name is missing. You guessed it - there is one dismissive reference to Fred Turner, and his Australian Grasses, in the text of Dark Emu, but no mention in the bibliography of any of Fred Turner’s books or writings, of which there at least four books and hundreds of papers and articles on indigenous plants, grasses and forage.

Why would a modern writer omit any positive reference to the giant in the field of Australian indigenous grasses? We will let the reader make up their own mind as to what motivates Mr Pascoe in this regard.

Introductory page 1 of Fred Turner’s Australian Grasses & Pasture.

Another reason Mr Pascoe may want to keep the work of Fred Turner quiet is because one of the themes running through Mr Pascoe’s Dark Emu is that the first settlers ignored indigenous knowledge and the benefits of the plants that they found here.

Not so.

As Fred Turner tells us in his Introductory, Captain Waterhouse [who arrived on the First Fleet, and was responsible for the first imports of, ‘the famous ‘Spanish breed’, forebears of the modern merino’ sheep to the colony, which he sold to John Macarthur and was therefore, ‘the true initiator of Australia’s fine wool industry.’ - Ref 1], spoke very highly of indigenous pasture grasses.

His good opinions of indigenous grasses had stood the test of time through the whole Colonial period of over 100years. This makes a mockery of Mr Pascoe’s claims that early Australian settlers, farmers and pastoralists failed to appreciate the value indigenous plants and knowledge.

Frederick (Fred) Turner (1852-1939), horticulturist and botanist, born Yorkshire, UK. In 1874 he left the Royal Vineyard Nursery, London, to work at the Brisbane Botanic Gardens.

It is highly disrespectful for Mr Pascoe to write-off the legacy of Fred Turner as just some Colonial author of a book on Australian Grasses that ‘doesn’t mention Aboriginal people at all’, (Dark Emu, 2018 reprint, p43).

This is doubly disrespectful given that, not only did Fred Turner refer to ‘the aborigines’ in his writings, but the Australian Dictionary of Biography tells us he actually undertook extensive botanical excursions on which he spent six weeks with the Aborigines.

Fred Turner was very highly regarded in his time and is still today, by those in the field, as evidenced by the fact that researchers even referred Mr Pascoe to Turner’s book.

From the Australian Dictionary of Biography we learn that, Fred Turner,

started work in botany and horticulture at the royal nurseries at Handsworth, Yorkshire, and Hammersmith, London.

He collected plants in Britain, Europe, the Canary Islands and South Africa.

In 1874 he left the Royal Vineyard Nursery, London, to work at the Brisbane Botanic Gardens. Encouraged by the director Walter Hill, he improved the gardens and was praised in parliament.

During extensive botanical excursions on which he spent six weeks with the Aborigines, he collected 'upwards of 10,000 specimens', among them the Fraser Island creeper (Tecomanthe hillii), which he boldly declared was, 'the rarest Australian plant'.

In 1880 he joined the grounds staff of the Botanic Gardens, Sydney.

in 1881 Turner was invited 'to re-design and beautify Hyde Park, Sydney.'

In May 1890 Turner was appointed economic botanist in the new Department of Agriculture. He received 'over 2000 letters' in 1892 and in 1890-93 contributed some 140 articles to the department's Agricultural Gazette of New South Wales. He mainly wrote about crops, weeds and toxic plants, grasses, pasture plants and agricultural procedures.

His retrenchment in 1893 [during the Australian banking crisis] was criticized as 'a public calamity'.

Turner also wrote regularly for the Sydney Morning Herald for over twenty years.

A member of the Linnean Society of New South Wales from 1891 and a councillor (1897-1912), he had contributed over 100 papers to its Proceedings by 1922.

In addition, he published four books, A Census of the Grasses of New South Wales (1890), Forage Plants of Australia (1891), Australian Grasses (1895) and Australian Grasses and Pasture Plants (1921).

He gave evidence before the royal commission on forestry. His work became widely acclaimed.

He succeeded Sir Ferdinand von Mueller as consulting botanist to the Western Australian government.

He was nominated by Mueller as a fellow of the Royal Horticultural Society, London, in 1888, he also became a fellow of the Linnean Society of London in 1892.

In 1907 he completed three manuals for Anderson & Co., seedsmen.

Turner recorded that he had travelled over 50,000 miles (80,467 km) 'on the Australian continent from Cleveland Bay and Kuranda in Northern Queensland to the vicinity of Perth in Western Australia', collecting material and popularizing indigenous fodder plants.

By all accounts Fred Turner was a highly respected Australian botanist and horticulturalist who interacted closely with Aboriginal people to gain a deep understanding of Australia’s indigenous plants, of which he wrote prolifically.

For Mr Pascoe to flippantly dismiss Fred Turner and his book, Australian Grasses with the comment, ‘doesn’t mention Aboriginal people at all’, is a massive travesty.

Isn’t it time to consign Dark Emu to the compost bin?

Ref 1 - Tucker, M.S., Elizabeth Macarthur, The Text Publishing Company, 2018, p116.

Note 1 - The ABC used to claim that Pascoe, as did Pascoe himself, was a ‘Boonwurrung, Yuin and Tasmanian man’, but now they seem to have heeded Michael Mansell’s warning that Pascoe is not Tasmanian Aboriginal and dropped that tribe.