Affirmation by Association - The March of Crap Through Our Art Galleries

“What has our culture lost in 1980 that the avant-garde had in 1890?

Ebullience, idealism, confidence, the belief that there was plenty of territory to explore, and above all the sense that art, in the most disinterested and noble way, could find the necessary metaphors by which a radically changing culture could be explained to its inhabitants.”

― Robert Hughes, The Shock of the New

This post is more about an observation, rather than an explanation, of where we find ourselves as a society today, beset as it is by Identity Politics.

As a Victorian, I have always tried to make a visit to the Art Gallery of NSW pretty much every time I came to Sydney. A particularly favourite collection in the gallery was the late 19th century/early 20th century paintings in the Grand Courts, on the ground floor of the South Building. The artists on display there were likes of Tom Roberts, Arthur Streeton, Dian Teague, Frederick McCubbin, John Glover, and many others.

These artists provided for me a thought-provoking and satisfying view of how I saw my country, Australia.

Like many Australians I suspect, there was something very soothing and comforting, but also at times invigorating, to be gained by spending an hour or two sliding around the walls of this picture gallery, absorbing a dose of old ‘Australiana.’

But, in the ‘weird world’ of 2023, where we now find ourselves, I have finally noticed some changes that have started to appear in this gallery of colonial and early Federation artists.

New ‘artists’, who claim to be of Aboriginal descent, and who are from the much later period of late 20th-early 21st century, are being curated into this collection. Their so-called ‘art-works’ are being inserted alongside my old favourites.

To me, the result is jarring and totally destructive to the ambience I used to feel in this Federation-era (ca1900) gallery.

Perhaps others might feel the same confusion and annoyance?

For example, in the two stock images below, prior to this ‘Indigenisation policy’, young Australian visitors can be seen to be immersed in the study of their country’s artworks from this colonial/Federation period.

The third image is mine, taken in 2023 in the same section of the gallery, which shows some of the newer Aboriginal artworks on the walls, as well as a collection of what I would describe as, ‘rubbish wire-item’ installations, on the floor (on left of photo).

The Art Gallery of NSW, “Colonial & Federation” collection in 2023, which includes various late 20th-early 21st century Indigenous artists - ‘photo-collage’ images on walls and ‘rubbish wire-item’ installations on the floor (see examples below).

Why would the curators at the gallery allow this to happen, given that there are other sections of the Art Gallery of NSW where Indigenous artworks are quite proudly and rightly curated in much more appropriate and artistically logical settings?

In this post, we invite our readers to see a small selection of what is occurring, by this juxtaposition of the new Indigenous ‘artworks’ with the existing colonial and Federation Australian artworks, in this section of the Art Gallery of NSW.

1. Trying to Affirm that the Photographic Craft of Bidjara Aboriginal man, Christian Thompson, is on a par with the painting art of Violet Teague.

The curators at the Art Gallery of NSW have juxtaposed a 2003 photograph, taken in down-town Melbourne, of a modern day model wearing ‘Victorian-era’ [replica?] clothing and holding a replica of an Aboriginal shield, with the 1909 painting, Dian dreaming, by Violet Teague.

Are the curators suggesting to their audience that these two pieces are artistically in the same league or even should be? Are they asking viewers to think about how the two pieces relate to each other, or what the photograph could possibly offer us as we contemplate the painting by Teague?

In my opinion, all the curators have achieved is to destroy the ambiance created by the connectedness that the original colonial and Federation-era artworks gave their audience. Can’t the curators appreciate how the emotional concentration of the viewer may be upset by placing these two items together, separated as they are by 100 years of technology, culture and meaning?

Or is that their plan? To ‘shock’ Australians out of any connectedness they may be developing with their colonial past, by confronting them with the newer, blunt realism that is possible with a concocted photograph?

2. Derivative ‘collage artwork’ made in the ‘High School Art Class’-style by Wiradjuri Aboriginal man, Andrew Brook, compared to a painting by Frederick McCubbin.

An ‘artwork’ called, Australia VI Theatre and remembrance of death, by Andrew Brook, who claims that he is a Wiradjuri Aboriginal man, was created in 2014, and ‘gifted’ in the same year to the Art Gallery of NSW.

Currently it occupies a prominent place in the gallery, above Frederick McCubbin’s 1896 painting, On the wallaby track.

To me, Brook’s artwork is deeply disappointing and its placement in the collection detracts massively from the connectedness that all the older paintings have with each other on this wall.

Brook has not created anything artistically unique, by using the skill of a real artist, trained in the techniques of traditional drawing or oil painting. All he has done is to copy a photographic print of a scene originally drawn/etched by the others in the 1850-60s and then expanded it in size and printed it onto a gold paper/board base. Hardly a creative, skilful or original artwork - more just like an ‘art-project’ by a high-school student, who is up with all the latest technologies.

In my opinion, this is a perfect example of my observation of how some artists seem to be just ‘try hard affirmationists’ :

‘Look at what I did today, mum, in art class!

Lovely Andie!!

Uncle Geoff knows someone down at the gallery - let’s see of he can get them to hang it next to their McCubbin. That will give you some real cred., even if he has to donate it to them.”

Wiradjuri and Celtic Australian artist, writer and curator Andrew Brook.

“Growing up with an Aboriginal mother and father of Celtic and Jewish ancestry, I always was interested in why my mum's family or my life, the experience of that identity, was not more in the public arena, especially in education” - Andrew Brook, Wiradjuri artist

Brook Andrew’s video SMASH IT and The Pledge draws its title from the artist’s practice of agitating colonial archives in order to subvert and rewrite dominant narratives of the past… Image, sound, and text overlap and splinter, entering into tension with one another to reveal and unravel power relations between coloniser and colonised, visible and invisible…SMASH IT draws attention to historical events that have occurred in different places and times and their contemporary legacies, connecting traumatic histories in Australia with international experiences and discourse. Excerpts from a series of interviews the artist conducted with First Nations leaders Marcia Langton, Wesley Enoch, Lyndon Ormond-Parker and Maxine Briggs about cultural protocols, appear alongside imagery of defaced and destroyed colonial monuments and the sounds of demonstrators commanding attention through shouts, declamations and chants.

Interspersed throughout is footage from Andrew’s earlier artwork The Pledge, a revised version of the 1955 melodrama Jedda, the first feature film made in Australia to use Indigenous actors as lead characters and the first shot in colour. Overlying the film’s imagery with new subtitles, Andrew rewrites the original film’s love story into a science fiction narrative to reflect on colonial violence and genocide. Ending with the Wiradjuri word ‘NGAAY’ meaning to ‘see’, SMASH IT brings colonial archives into relations with the present moment, inviting viewers to experience these images anew and to reimagine a different legacy. Sources: here and here

3. But wait there is more.

As I moved around the Grand Courts gallery, I saw a photograph of a dead galah on a cracked bed of dry earth, hanging right above a lovely Arthur Streeton landscape.

The curators appear to have no desire to let the gallery’s visitors just enjoy, uninterrupted by modernity for a hour or so, some of our culture’s best colonial and early 20th century paintings by Streeton and others.

Instead, we are given a dose of the ‘shock of the new’ and lectured on a bizarre ideological link between Christianity and its alleged impact on Aboriginal cultural practices and the environment, all through the medium of a dead galah. Unbelievable.

4. ‘Kindy’ Painting Meets Real Painting

Another piece of ‘artwork’, plonked into the middle of some fine paintings of the Gold Rush era, is by Marlene Gilson, who claims to be a Wadawurrung Aboriginal woman.

Unfortunately, yet again, its inclusion in this part of the gallery’s collection is totally out of place. I am sure there must have been a more appropriate section of the gallery where the ‘primitive-style’ [‘naive’] of this politically-biased painting would be more properly curated [See another author’s critique of Gilson’s work].

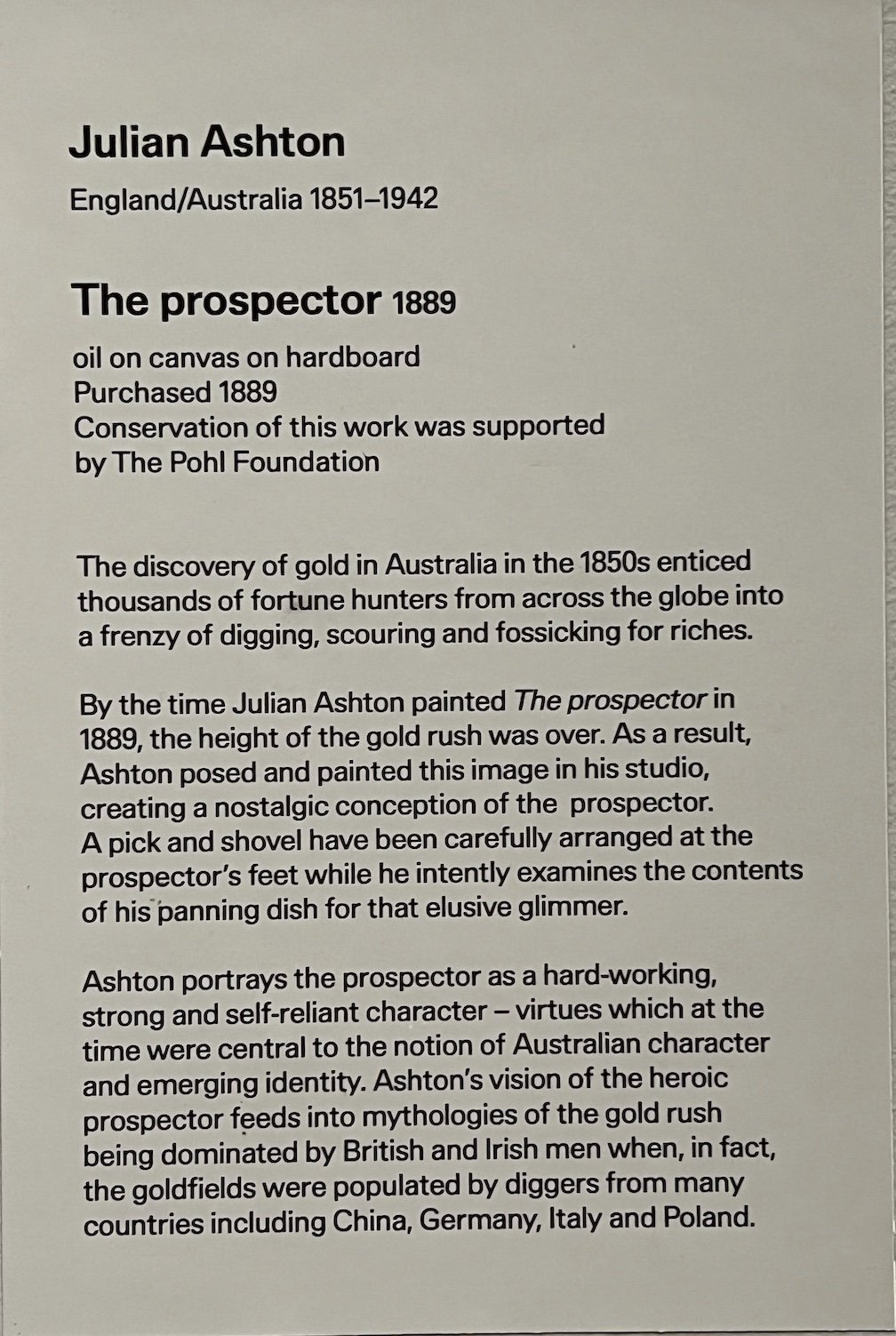

In my opinion, its presence in the Grand Courts gallery greatly detracts from the ‘real’ paintings by artists such as Walter Withers and Julian Ashton.

Once again, the continuity and emotional journey of my experience as a viewer of my culture’s heritage is broken by juxtaposing this 2020 painting against the artworks from the 1880s.

The curators at Art Gallery of NSW have juxtaposed a piece of modern, ‘primitive-style’ of artwork with colonial paintings of the Gold Rush, to poor effect for those viewers who just wanted to immerse themselves in our culture’s colonial past for an hour or two.

Aunty Marlene Gilson: Born Warrnambool: 1944 Clan – Wathaurung (Wadawurrung)

Ballarat, My Country, 2020 - Aunty Marlene Gilson: Born Warrnambool: 1944 Clan – Wathaurung (Wadawurrung). “Marlene Gilson’s multi-figure paintings work to overturn the colonial grasp on the past by reclaiming and re-contextualising the representation of historical events. Learning her Wathaurung history from her grandmother, Gilson began painting while recovering from an illness. The artist’s meticulously rendered works display a narrative richness and theatrical quality akin to the traditional genre of history painting. Gilson, however, privileges those stories relating to her ancestral land, which covers Ballarat, Werribee, Geelong, Skipton and the Otway Ranges in Victoria.

Often including her two totems, Bunjil the Eagle and Waa the Crow, Gilson’s paintings not only reconfigure historical narratives, but display her spiritual connection to Country.

5. Envisioning Australia Only as a Binary: Arcadia versus The Holocaust

The relentless attempt by some to re-write Australia’s history as primarily one of Aboriginal dispossession and genocide, has also spilled into the Art Gallery of NSW.

The curators to my mind just seem lack any real maturity in being able to understand the beauty and depth of the positive feeling that one can derive from Arcadian art.

To many Australians the notion of Arcadia, and what it represents, runs very deep within our Australian psyche, even given that most of us may be entirely unconscious of it. It has been one of the driving forces of the Australian Project - the subconscious drive by our society of working peoples that has turned this dry, inhospitable, poor and difficult country into one of the most beautiful, successful and ‘lucky’ countries in the history of mankind.

But hey, lets just stick a depressing pastiche of death and environmental destruction amongst the Arcadian artworks to deflate any higher intellectual notions that the Bogan visitors might be feeling. We can’t have them feeling any pride in their own country and its history can we?

John Mather Scotland/Australia 1848 - 1916. A woolshed, Victoria 1889, oil on canvas, Purchased 1971

A Spoiler’s Curation - Having a Funeral at a Country Picnic

6. The Gate-Crashing Continues

The forcing of these new Aboriginal ‘artists’ onto the gallery’s visitors continued as I moved into the portrait section of the colonial Grand Courts gallery.

A particularly incongruous addition was a photograph by Dr Christian Thompson AO, who claims to be the great-great-grandson of “King Billy of Bonny Doon Lorne, a senior tribesman of the Bidjara people, who reigned for many years over the district”.

It is claimed that Thompson identifies himself as Bidjara (an Aboriginal Australian people of central southwestern Queensland), despite his additional heritages of Chinese Australian, Irish, Norwegian and Sephardic Jewish ancestry that are claimed to have been acquired from his parents. (Wikipedia bio).

Given this list of ‘mogrelity’, some of us might just wonder, isn’t he just Australian like the rest of us?

And regarding the inclusion of his ‘artwork’ - a photograph of him hiding behind a print of a portrait of Captain Cook - it just comes across as being self-indulgent. In my opinion, the curators are promoting ‘brand Thompson’ by giving his work a space in the colonial portrait gallery. This just gives him publicity and affirms his position as an artist, by placing his work alongside that of ‘real’ artists such as BE Minns.

Plus the curators get extra ideological brownie-points by denigrating a colonial icon such as James Cook in the process!

Similarly for Michael Riley’s photographic portrait, Maria.

What were the curators thinking by plonking a modern-day photograph amongst a set of colonial painted portraits, done 120 years before? The only conclusion I can come to is that they want us to believe that Riley’s work is the artistic and cultural equivalent of a Backler oil portrait in the story of Australia.

They are entitled to that view, but the place for Riley’s work is not here in this section. His work should be given the appropriate respect by being exhibited in a separate section, where it can be properly curated within the correct context.

To me, the curators just seem to be using Riley’s modern work to disrespectfully disrupt the continuity that any viewer might be having with the colonial portraits - it is almost as if the curators are saying, “can’t have those Bogan viewers enjoying portraits of their ancestors without being forced to acknowledge the political power of blak women’.

7. The March of the ‘Rubbish wire-item’ Installations.

A visit to any of those old junk shops that exist in the small dying country towns on a ‘Tourist Trail’ [think Inglewood and Wycheproof in Victoria] would yield a treasure trove of junk for an ‘artist’ such Karla Dickens to use in her ‘artworks’. Old, battered bird cages, mutilated dolls, boxing glove sets and assorted kitsch paraphernalia from the 1950s - it’s all there in abundance, in the shops and in her ‘artwork’.

So how disppointing to find that this junk now has to be navigated around in one of the country’s premier colonial artwork galleries. So much for respecting the sensibilities of visitors who come to be immersed in some real art, that of our colonial and Federation periods.

So there you have it - the Invasion of the Culture Snatchers is underway, with the Indigenisation of our colonial art galleries, with artwork that pretty much nobody would notice, or seek out, unless it was forced onto them.

It must be a sad time when an artist comes to realize that they are only known by those who they are seen with. Their legacy will be defined as Affirmation by Association.

We opened this post with a quote by the Australian, then American-based, art critic, Robert Hughes:

“What has our culture lost in 1980 that the avant-garde had in 1890?

Ebullience, idealism, confidence, the belief that there was plenty of territory to explore, and above all the sense that art, in the most disinterested and noble way, could find the necessary metaphors by which a radically changing culture could be explained to its inhabitants.”

― Robert Hughes, The Shock of the New

To our mind, Australian culture was definitely beginning to lose its way by the year 2000 (with the History Wars, rather than by 1980), from the ‘confident, ebullient idealism’ that used to be solely on display in the Grand Courts of the Art Gallery of NSW.

I think that is why this gallery was always so popular with the general Australian public - a place where the average punter could come and, for an hour or two, drink deep from a colonial Arcadian lake that was quintessential Australian.

The gallery’s curators seemed to have also read Hughes’ quote, but come to a completely different conclusion. They indeed decided to install artwork that had the '“necessary metaphors by which a radically changing culture could be explained to its inhabitants.”

Unfortunately however, in my opinion, they have misread the room. Adding depressing and ideological ‘crap’ as a ‘metaphor’ for Indigenisation, or the “radically changing culture” that indeed has been occuring over the past 20 years, was bound to back-fire on them.

This addition of ‘crap-art’ will indeed ‘explain to the inhabitants’ that their traditional Australian culture is ‘radically changing’ - but, as is becoming evident to many of us inhabitants, it will be for the worse.

And hence this new ‘art’ movement and attack on our traditional Australian culture will be rejected. This is becoming apparent, I believe, in such places as the Voice referendum. The polls are indicating a massive fall off for support for the Yes case. My sense is that the average punter, which includes many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, will increasingly reject this ‘radical’ revision, and Indigenisation, of our Australian culture.

Australians want at least one small Arcadian oasis for their unique art. They don’t want it grate-crashed by ‘look-at-me’ artists who are only known by the company they keep.