“Sophisticated" Aboriginal Houses - really?

Number 1: Location, location, location !

In 2007, Queensland University press published a beautiful and detailed academic book by Paul Memmott on Australian Aboriginal architecture called, Gunyah Goondie + Wurley. This reference book is heavily drawn upon by Mr Pascoe in his arguments in Dark Emu that, “Aboriginal people did build houses and lived in villages and that some of the most sophisticated structures were of a “dome style” (Dark Emu, 2018 reprint, pp 118-123). Of the very large number of photographs of aboriginal architecture in Gunyah, Goondie + Wurley, Mr Pascoe selectively chooses only two for his book to support his argument, Figure 1 and 2 below.

Figure 1 : Supposedly an example of an “Australian Aboriginal Pointed Dome House” in Dark Emu

Figure 2 : Supposedly an example of an “Australian Aboriginal Pointed Dome House” in Dark Emu.

Unfortunately, these two are not of Australian mainland Aboriginal origin, but are in fact from the Torres Straits, and clearly show a Melanesian style with Polynesian influences. See Figures 1.4 and the accompanying text below, from Paul Memmott’s Gunyah Goondie + Wurley, where he notes:

“A note on Torres Strait Islander ethno-architecture. Vernacular styles of building, which were distinctly different from those of Aboriginal Australia, occurred in the Torres Strait Islands, combining split bamboo, woven pandanus and coconut palm leaf, and grass thatch. Architecturally, this is best classified with Melanesian styles, albeit with Polynesian influences. Apart from Figures 1.3 and 1.4, there is no [Torres] Strait ethno-architecture [in this book by Paul Memmott] as it is a separate cultural study with a number of regional styles.” (emphasis added)

Caption for Figure 1.4 is :

“The Meriam people of the eastern Torres Strait Islands constructed pointed domes (akur meta) up until the turn of the 19th century, when their house styles underwent change under mission influences. A traditional medium- sized dome had an interior radius of about 2.85 metres and an interior height of 3.75 metres. Each dome accommodated a nuclear or an extended family. Construction was of (a) bamboo canes arranged in transverse arcs and tied together; (b) a cladding of blady grass (Imperata sp.) fastened with split bamboo lathes. (Fig 1.4 a) Photograph from the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies- AIATSIS. [Miss attributed in Dark Emu] (Fig 1.4 b) Photograph from Queensland museum.”

[So no Australian Aboriginal “sophisticated houses” to see here, only what appears to be ‘Cultural Appropriation’ of Torres Strait Islander architecture to bolster Mr Pascoe’s Theory].

Figure 1.4 (a) & (b) : Torres Strait Island Pointed Domes of Melanesian Style with Polynesian influences.

Excerpts and photographs reproduced here for review and critique purposes only - Fair use claims are made for text and images sourced from ATSIS,-A.C.Haddfon collection, Queensland Museum, Memmott P., Gunyah Goondie + Wurley, QUP, 2007.

Number 2 : Stretching the definition of “comfortable houses”!

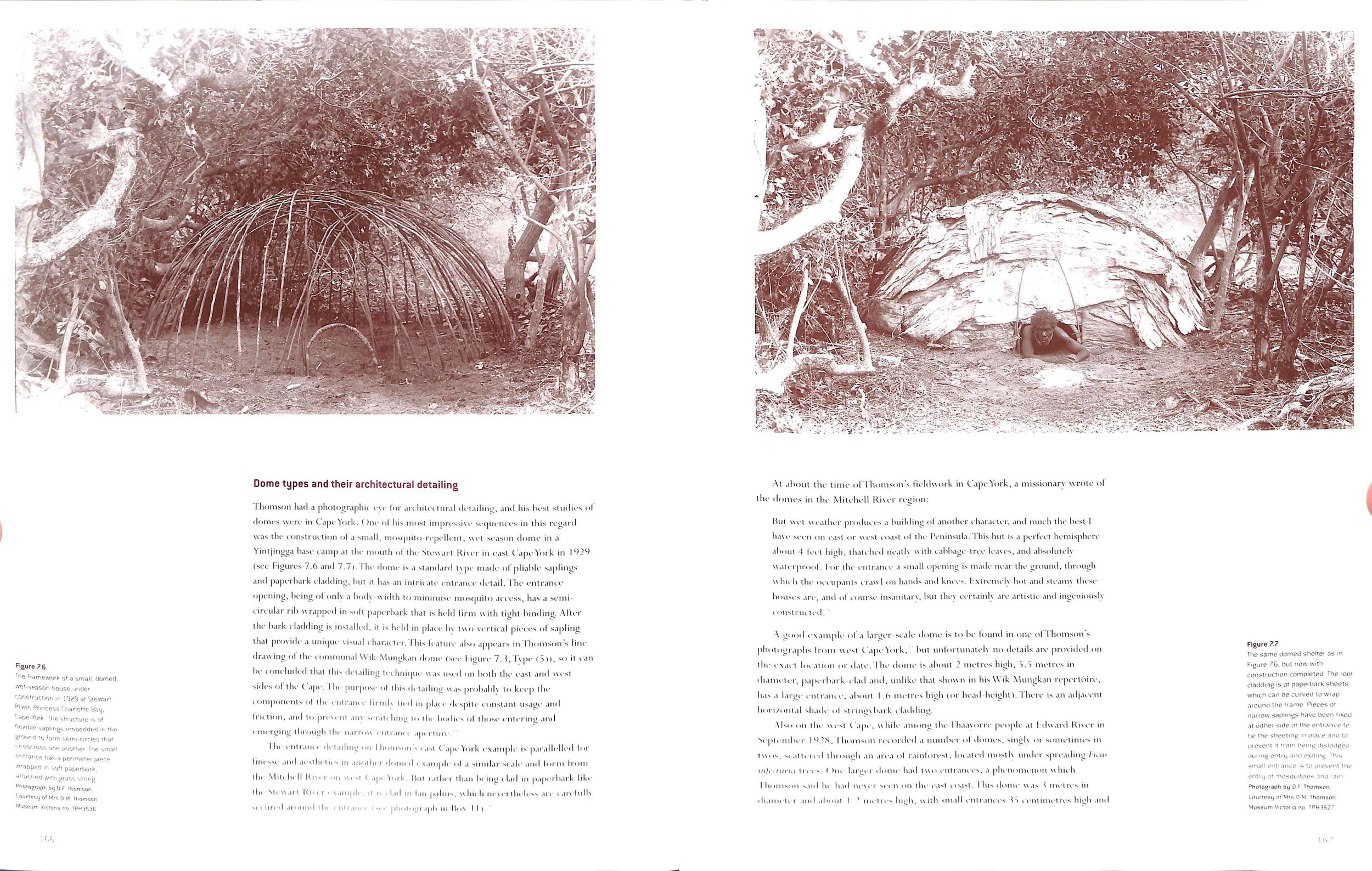

Further quotes by Mr Pascoe (Dark Emu, 2018 reprint, pp 117 and 119) are perhaps stretching the contemporary understandings of words such as, “scale and sophistication of Aboriginal housing”, and “the wet season could be survived in comfort”. When we actually track down one of the references he quotes, namely Ref #39, Memmott P., Gunyah Goondie + Wurley, QUP, 2007, p166, as shown below in Figure 2, one wonders whether Mr Pascoe may have previously worked as a real-estate agent! These Aboriginal huts were appropriate for the times and expertly constructed out of local materials, but it is very misleading to suggest they are “sophisticated” and “comfortable” as we understand the meaning of those words nowadays.

Figures 7.6 and 7.7 - According to Mr Pascoe, these photographs show an example of where “Aboriginal people in the southern Gulf of Carpentaria area created large domed, grass-covered shelters with small entrances so that the opening could be easily closed. These structures were adapted so the wet season could be survived in comfort, and so insects could be repelled by having a small, smoky fire within”. (Dark Emu, 2018 reprint, p118-119).

If one actually reads the contemporary description by a missionary, who actually saw the domes, on page 167 of Mr Pascoe’s quoted reference above, we can get a feel for the real conditions of living in these “houses”.

“But wet weather produces a building of another character, and much the best I have seen on east or west coast of the Peninsula. This hut is a perfect hemisphere about 4 feet high, thatched neatly with cabbage-tree leaves, and absolutely waterproof. For the entrance a small opening is made near the ground, through which the occupants crawl on hands and knees. Extremely hot and steamy these house are, and of course insanitary, but they certainly are artistic and ingeniously constructed”.(Memmott, P., Gunyah Goondie + Wurley, QUP, 2007, p167).

Excerpt and photographs reproduced here for review and critique purposes only - Fair use claims are made for text and images sourced from Museum Victoria (D.F & D.N Thomson), Memmott P., Gunyah Goondie + Wurley, QUP, 2007.

Number 3 - The Missing Hypothetical

Mr Pascoe includes a sketch, Figure 1 below, which he labels “A reconstruction of a Gundidjmara village, western Victoria (Paul Memmott), (see Dark Emu, 2018 reprint, p128). The use of the term “a reconstruction” implies to the reader that some archaeological work has been done by peer-reviewed archaeologists and academics to justify this sketch of the village. On closer inspection we find that one of Mr Pascoe’s references, Paul Mammott, (Gunyah Goondie + Wurley, QUP, 2007, p194 , Figure 8.3 below), who originally prepared this sketch of one village house, clarifies his work with the justifiable adjective “hypothetical” - an inconvenient word Mr Pascoe just seems to have left out of the caption used in his Dark Emu book. Mr Pascoe also drops the word “house” and suddenly he has a whole village instead of just one house!!

Figure 1 : Caption reads, “A reconstruction” of a Gundidjmara village, western Victoria" [Paul Memmott]” - Dark Emu, 2018 reprint, p128.

Figure 8.3 Caption reads, “A hypothetical reconstruction of a Gundidjmara village house, with stone wall and timber-framed, domed roof clad in peat sods. Prepared by the author’” [Paul Memmott].

Furthering the critique of Mr Pascoe’s claims for the “stone houses” we checked his statement, “Apart from the remains of the houses themselves, the evidence is supported by early colonists such as James Dawson and Peter Manifold, who described the buildings in great detail (ref 47). We checked reference 47, which refers only to “Dawson p10”. We could not find a reference to Peter Manifold anywhere in the reference list of Dark Emu. And the words of James Dawson in Australian Aborigines, (Publisher George Robinson, 1881, Chapter 6, p10-11), with respect to the stone habitations of the Aborigines are not that detailed or flattering, viz:

“ In some parts of the country where it is easier to get stones than wood and bark for dwellings, the walls are built of flat stone and roofed with limbs and thatch. A stony point of land on the south side of a lake near Camperdown is called ‘karm karm’ , which means ‘buildings of stones’, but no marks or remains are now to be seen indicating the former existence of a building there.”

Although these “stone” habitations were semi-permanent during the several months long eel-season, the Aborigines still continued their semi-nomadic, hunter-gatherer life-style during the summer months. A photograph of the remains of one of these Tyrendarra (Lake Condah) stone “house” as they appear today, indicates that the word ‘sophisticated’ might not be the first adjective one thinks of when describing these huts (Figure 2).

Figure 2: A contemporary photograph of a Tyrendarra stone “house”- c/o Tripadviser

UPDATE OF OCTOBER 1ST 2021

In June 2021, anthropologist, Peter Sutton and archaeologist, Keryn Walshe, published their book Farmers or Hunter-gatherers? The Dark Emu Debate, which decimated the Dark Emu theory of Bruce Pascoe. Sutton & Walshe use facts, evidence, scholarship, science, experience and consultation with the Old People to expose Dark Emu to be basically a work of ‘fiction’ - it is all ‘just made up.’

To answer the comments of a reader , “beeden” (see comments posted below), we have presented here an excerpt of a few pages from Sutton & Walshe’s book regarding their analysis of Bruce Pascoe’s claims for the ‘permanency’ and construction of ‘stone’ Aboriginal houses.

Also here below are the full pages from the settler James Dawson’s account, which are referred to by “beeden”.

Based on our reading of Sutton & Walshe and James Dawson, we still say that it is wrong for Pascoe to lead his readers into believing that Aborigines lived in 'permanent stone villages that were ‘sophisticated’.

In fact, Aboriginal huts generally were made with the minimum amount of effort as possible to be ‘fit-for-purpose.’ Stone was used more frequently when timber was scarce. Stone was not used in general because across Australia Aboriginal societies usually found all the wood, bark and brush they needed to slap up a shelter with the minimum of effort (See this clip from 04:20 on the construction of a shelter). Their shelters and huts were not ‘sophisticated’ - they didn’t have hinged doors, chimneys, glass-paned windows, timber or stone floors or room separation for example like the ‘sophisticated’ houses of the British.

Pages on Habitations of Aborigines in James Dawson’s Australian Aborigines, 1881

![Figure 1 : Caption reads, “A reconstruction” of a Gundidjmara village, western Victoria" [Paul Memmott]” - Dark Emu, 2018 reprint, p128.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5cf30ff26df8f90001ae648d/1560170482254-UQZ3C6CPRZOIKQK6I2Y2/Dark+Emu+Reconstructed+village.jpg)

![Figure 8.3 Caption reads, “A hypothetical reconstruction of a Gundidjmara village house, with stone wall and timber-framed, domed roof clad in peat sods. Prepared by the author’” [Paul Memmott].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5cf30ff26df8f90001ae648d/1560168782505-VHYUVTDBGHSTFDV6XR0F/Hypothetical+Village.jpg)